Banbury Castle was a medieval castle that stood near the center of the town of Banbury, Oxfordshire. Work on the castle began in either 1126 or 1135 by Alexander, the Bishop of Lincoln, who controlled Banbury. The 12th-century castle had a large, approximately square, curtain wall with mural towers, enclosing a probable manor house.

The castle was redeveloped around 1225-1250 by the bishops. The new castle had two rings of concentric walls defended with ditches and towers, enclosing the main buildings at the center of the fortification. It remained in use until the Reformation, when it passed into the hands of the Crown and then leased on.

Increasingly ruinous, Banbury Castle played an important part in the English Civil War of the 1640s, being held by Royalist forces in several sieges. After the war, Parliament ordered it to be destroyed. The site was gradually redeveloped between 1648 and the 1970s; nothing now remains of the castle.

History

11th-12th centuries

The settlement of Banbury lay at a strategic crossroads, linking the Thames Valley with the Midlands. During the Anglo-Saxon period, the Bishop of Dorchester had acquired a large estate there, but after the Norman Conquest, the see was moved to Lincoln. The bishops of Lincoln continued to control Banbury, which formed a centre for running their north Oxfordshire estates.

The construction of Banbury Castle began in either 1126 or 1135, under the direction of Alexander, the Bishop of Lincoln. Alexander was known in Rome as “the magnificent” on account his construction work, and also constructed castles at Sleaford and Newark. The castle lay on the north side of Banbury, which Alexander had redesigned as a planned borough.

Occupying 7 acres (2.8 ha), the castle was approximately square, had a embanked curtain wall around the outside with a small ditch and square mural towers. There was probably a manor house in the center and other service buildings around the edge. The castle was protected by a castle-guard drawn from estates around Banbury owing service to the bishops.

The castle was later confiscated from Alexander by King Stephen in 1139, but appears not to have been completed at that point, as it was returned to the Bishop later that year.

13th-14th centuries

The castle was strengthened between 1201–1207 during the reign of King John and continued to be used by the bishops of Lincoln.

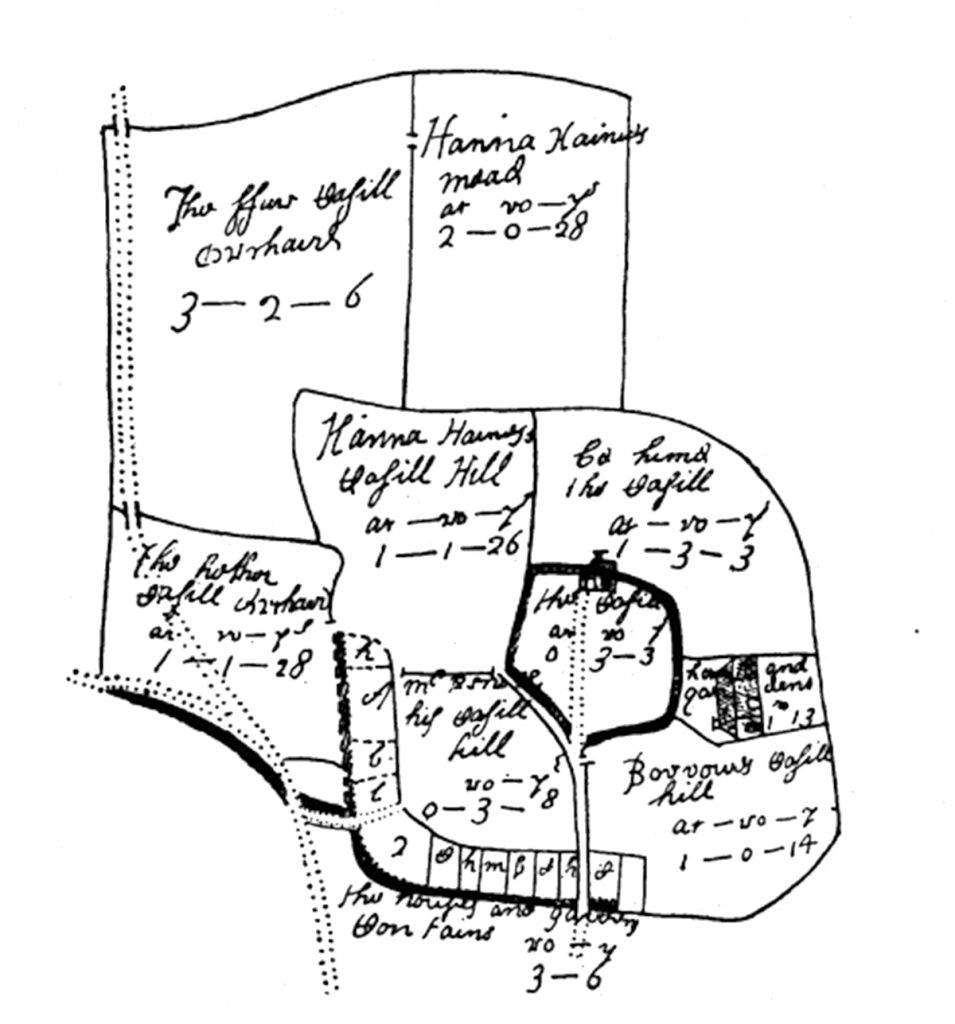

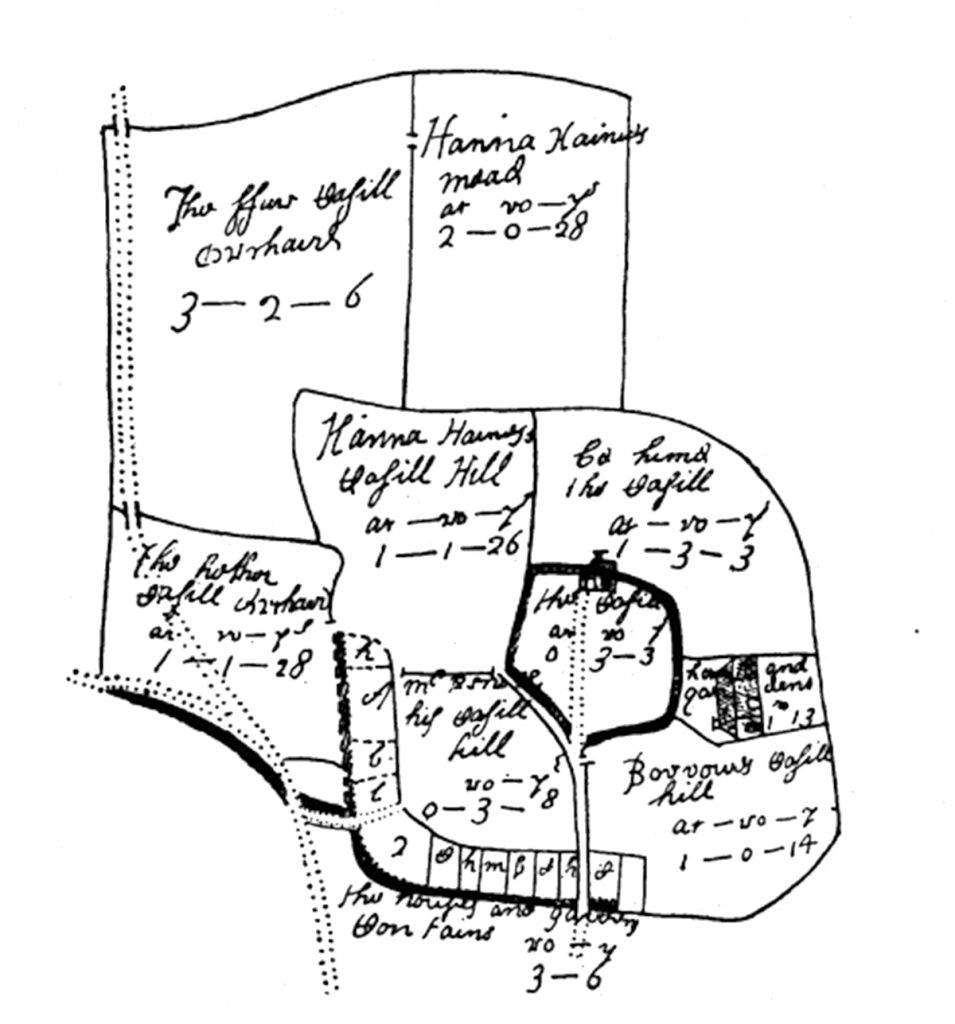

Around 1225-1250, the castle was entirely rebuilt, probably by either Bishop Hugh of Wells or his successor, Robert Grosseteste. The new castle had two wards. The outer wall was reconstructed with a deeper outer ditch, circular mural towers and a very large inner ditch. The entrance was protected by a gatehouse. Within the outer wall of the castle was a concentric polygonal curtain wall with large towers, an inner ward covering around 0.75 acres (0.30 ha), protecting the main buildings.

The historian John Kenyon concludes that Banbury Castle was “remarkable for its early concentric shape”, which is usually seen in later castles such as Harlech or Beaumaris. In addition to providing stronger defences, the reconstruction work would also have given the castle additional protection against the environment: the original fortification had been built on soft, unstable wet ground, and the deeper foundations and new ditches would have helped to protect and land slippage.

The castle contained an eccelesiastical prison by 1276, run by the bishop to hold clergy and laymen. The prison was situated near the main gate. The castle also had two watermills, a fish pond, meadow land and gardens.

16th century

At some point in the 1520s or 1530s, a large “mansion house” was built within the castle walls, probably on the east side of the outer ward. This was commented on by the antiquarian John Leland, who visited Banbury and described the castle in the 1540s:

“There is a castle on the north side of this area [the market place] having two wards and each ward a ditch. In the utter is a terrible prison for convict men. In the north part of the inner ward is a fair piece of new building of stone”

John Leland, antiquarian

The Reformation brought an end to the rule of the bishops of Lincoln in Banbury. In 1547, the castle was bought by Edward Seymour, the Duke of Somerset. It passed shortly afterwards to John Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland, who sold it on to the Crown in 1551.

Shortly after this change in ownership, the prison in the castle diminished in size, vanishing entirely by the 1560s. By now the fortification was in poor condition, with one survey describing it as “in great decay”. The prison was reestablished and operated from the 1580s until around 1612. It was used to holding recusants, Roman Catholics who refused to attend Church of England services as was then required by law.

In 1595, the castle was leased to the Oxfordshire nobleman, Richard Fiennes, the lord of Saye and Sele.

17th century

In 1642, the English Civil War broke out between the Royalist supporters of Charles I and the supporters of Parliament. Banbury Castle was initially held for Parliament by William Fiennes, the son of Richard, and the castle was hastily refortified and garrisoned with around 1,000 men.

After the inconclusive Battle of Edgehill that October that marked the beginning of the true fighting in the war, Charles marched south into Oxfordshire and -despite concerns from some of his officers that he lacked sufficient forces for the task – besieged the castle. Large parts of the Banbury garrison had Royalist sympathies, however, and the forces guarding the castle quickly surrendered, giving up their valuable arsenal of firearms. Banbury was then reportedly pillaged by the Royalist forces.

The fortifications were strengthened, with changes made to various parts of the outer wall. The castle became a key part of the Royalist war effort in Oxfordshire, being used as a secure base for collecting taxes and materiel from the surrounding countryside, as well as military raids against Parliamentary forces.

The war slowly turned against the Royalists, and in July 1644 the castle was besieged by Parliamentary forces under the command of William Fiennes. The royal governor inside, Sir William Compton, held out fiercely. Houses around the castle were burnt down to provide an open line of fire for the defenders, and the two sides exchanged shots with cannons and muskets. Parliamentary forces attempted to undermine the castle’s walls, but encountered underground “springs of water” that forced them to close down their tunnelling work.

In mid-September, Parliament breached part of the south-western outer walls with cannon and made an assault, which was driven off. In October, William’s brother James, the Earl of Northampton finally relieved the siege, driving off Fienne’s forces.

As the war deteriorated for the Royalists during 1645, the plundering by the Banbury Castle garrison around the surrounding area worsened. In November, Charles I dined in the castle on his way south to Oxford.

In January 1646 Sir Edward Whalley placed the castle under siege again with a force of 3,000 men. Both Whalley and Compton pursued an active campaign, with extensive mining, counter-mining and gun-fire. By now the Royalist cause was collapsing, and after the King surrendered to Scottish forces in April, a few weeks later Compton and his force of 300 men themselves surrendered the castle in May. Major Adams became the new governor.

In 1646, Parliament gave orders that the castle be slighted, or deliberately damaged to put it beyond military use – but advised this be done in such as way as to not damage Fiennes’ property any more than was strictly necessary. The initial plans to simply damage the earthwork defences were challenged by the citizens of Banbury, who wanted the entire of the castle to be pulled down and for the stonework to be used for the repair of the town, which had been badly damaged during the war. Parliament agreed to this, and Fiennes was paid £2,000 by compensation.

Following the destruction, only a stable and a storehouse survived, used by Fiennes to hold the Banbury hundred courts, and some of the earthworks. Cottages, a row of houses and other buildings gradually built across the wider site.

18th-21st centuries

By 1778, the Oxford Canal had cut across the north-east corner of the castle site. In 1792, Fienne’s descendant, Gregory Eardley-Twisleton-Fiennes, the Lord of Saye and Sele, sold the land in two halves, which were the following year consoldated into a single holding by James Golby, a local coal merchant. The castle site remained in the ownership of the Golby family into the middle of the 19th century.

The south-western half of the site were developed over in the 19th century for housing and factories, forming Castle Street, which marked the former site. The inner ward of the castle was for several decades at the start of the 19th century used as gardens, known as the Castle Gardens. The northern site of the site lay generally undeveloped until the 20th century.

The redevelopment of central Banbury in the 1970s led to several archaeological investigations in 1972, and 1973-74. These proved the original form of the castle, and generated a three-stage model of the development of the site. Nothing now can be seen of Banbury Castle.

Bibliography

- Beesley, Alfred. (1841) The History of Banbury. London, UK: Nichols and Son.

- Fasham, Peter. J. (1973) “Banbury Castle: A Summary of Excavations in 1972”, Cake and Cockhorse, Volume 5 Number 6 pp.109-116.

- Fasham, Peter. J. (1983). “Excavations in Banbury, 1972: Second and Final Report”. Oxoniensia 48. pp.71–118.

- Kenyon, John R. (1990). Medieval Fortifications. London, UK: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-7886-3.

- Rodwell, K.A. (1976) “Excavations on the Site of Banbury Castle, 1973-4” Oxoniensia Volume 41 pp. 90-147.

Attribution

The text of this page is licensed under under CC BY-NC 2.0.