A sequence of bridges were built over the River Medway between the 1st and 20th centuries at Rochester, England, several of them fortified. The first bridge at Rochester was built by the Romans after their invasion in 43 AD. It had massive stone piers supporting a wooden superstructure, and linked London with the south-east of England.

The Roman bridge appears to have lasted into the Anglo-Saxon period; various nearby estates, the Bishop of Rochester and the King had collective responsibility for maintaining it. The bridge was involved in the First and Second Barons’ Wars and by 1343 was protected with a barbican and a drawbridge. It was in increasingly poor repair, however, and finally washed away during spring floods in 1381.

A replacement bridge was constructed just along the river, this time entirely in stone, with a drawbridge in the centre. Maintenance proved challenging and required the creation of an elaborate network of estates, controlled by a team of bridge wardens. The bridge was central to the Royalist defence of Rochester during the Second English Civil War of 1648.

By the end of the 18th century, the medieval bridge was proving less and less suitable for the increasing road and river traffic. After several phases of partial improvements, it was demolished and a new bridge constructed over the site of the former Roman bridge, opening in 1856. That bridge was then rebuilt at the start of the 20th century, and a former railway bridge was redeveloped alongside it to provide additional capacity in 1960. Both the “Old” and “New” bridges remain in use today, operated by the Rochester Bridge Trust.

History

1st – 8th centuries

Rochester’s first bridge was built across the River Medway in the Roman period. The settlement of Durobrivae, meaning “the fort by the bridges”, was established on an older Celtic site in the 1st century AD. A bridge was built where the Roman road of Watling Street cut across the Medway, sometime between 43 AD and the end of the century. The location was strategically important, linking London to the south-east of England, and in turn to the rest of the Roman empire on the continent.

The timber bridge crossed a large gap of fast flowing water. The initial bridge was probably constructed completely from timber by Roman military engineers after the invasion, with a permanent version using stone piers and a timber superstructure probably replacing it by the end of the century. The bridge’s piers were constructed on foundations of oak piles, driven into the gravel at the bottom of the river, and reinforced with ragstone rubble – they penetrated the river bed for up to 25 ft (7.6 m)to withstand the force of the river.

9th – 14th centuries

It is uncertain whether the Roman bridge at Rochester survived the collapse of Roman rule in the 4th century AD. It may have continued to be maintained into the early Anglo-Saxon period, or, either due to disrepair or the rising river levels during this this period, it might have fallen into ruin. In 604 AD, Rochester became the second see, or bishopric, in England, and would have continued to be strategically important.

By the late Anglo-Saxon period, there are records of a bridge at Rochester, on the same site as the old Roman one. The Anglo-Saxon kings of England had established wider laws regarding the maintenance of bridges, a task called bridgework, and Rochester Bridge was supported using a system called geweorc, or labour-service. Various estates near Rochester had a duty to maintain specific piers along the bridge, and the timber supports between them, with the King and the Bishop of Rochester each also taking responsibility for a specific pier.

From the records, it is clear that Rochester Bridge at this time had nine stone piers, at the very least reusing the earlier Roman foundations and probably much of the stonework. Two of these were “land-piers”, with their footing on the bank rather than the river bed. The overall length of the bridge was recorded as being 437 ft 6 inches (133.4 m) across. The piers were not evenly distributed, probably to allow for the faster and deeper water on the outer side of the river. The timber superstructure was probably made primarily from square oak beams, perhaps up to 50 ft (15 m) long and 1 ft 6 inches (0.46 m) across, with planking laid on top.

The bridge continued to be maintained after the Norman conquest of England in 1066, although it was dangerous to cross when windy, or on horseback, and there were various fatalities – it appears that there were no barriers on the sides of the bridge to prevent accidents.

As a strategic asset, Rochester Bridge was involved in both the First and Second Barons’ Wars. In 1215, King John took Rochester and attacked a force of around sixty of the barional rebels who were holding the bridge. Apparently successful, the King then broke down parts of the bridge to protect himself from attack, and took the castle.

In 1264, Simon de Montfort attempted to take Rochester, which was being held for the Crown. The townsfolk fortified the eastern end of the bridge, close to the city walls, with a wooden tower, and broke up parts of the bridge to block any advance. Despite this, de Montfort set fire to the fortifications and briefly took Rochester and placed the castle under siege.

The importance of Rochester Bridge to the defence of the town had become clear. By 1343, Edward III had constructed a barbican and a drawbridge on the western end of the bridge, possibly to defend against any French incursions.

The bridge was by now very old, and proving increasingly difficult to maintain. Nineteen serious repairs were required between 1277 and 1381, with the number of serious collapses increasing from the 1340s onwards. The bridge was ever more hazardous to cross, but when the bridge was out of action for repairs, any travellers across the river needed to use the ferry, which was even more dangerous.

The end finally came in February 1381. Rochester Bridge was once again in serious need of repairs, when ice built up in larger quantities further up river. There was a sudden thaw, huge chunks of ice drifted down stream, pushing up against the bridge and causing it to collapse and washing much of it away.

14th – 15th centuries

Following the collapse of the old bridge, a temporary ferry service was established, and several royal commissions were created to consider what course of action to pursue next. Initially, some hopes that the bridge could be repaired, but this became increasingly unlikely. Concerns were also raised that the old method of financing the repair of the bridge was no longer viable, placing too much stress on particular estates, and lacking adequate administrative controls.

In 1383, a new plan was put forward, involving building a stone bridge just upstream from the old one. The plan was led by Sir John de Cobham and Sir Robert Knolles, two prominent knights with landed interests in Kent, and was probably endorsed by Henry Yevele, a leading architect and specialist in bridge design. The project began in earnest in 1387, with John and Robert providing the majority of the funding.

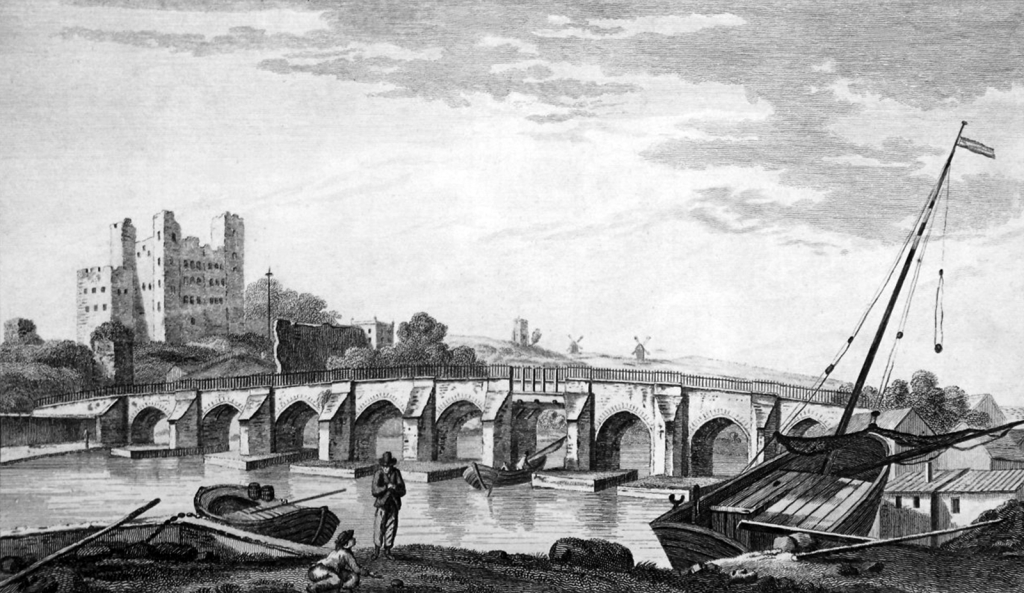

The new bridge was 560 ft (170 m) across and 14 ft (4.3 m) wide, with twelve piers which supported eleven arches. The piers rested on starlings, supportive bases 45 ft by 20 ft (14 m by 6.1 m) across, formed from masses of iron-tipped elm piles, and protected by chalk and a further ring of piles. Perhaps over 10,000 piles were involved in the construction. The surface of the bridge was paved with ragstone.

A drawbridge and winding-house rested in the middle of the bridge, controlled by the Crown. A counting-house and a storehouse were built at the eastern, Rochester side, along with the bridge chapel, which acquired a chantry of three chaplains in 1395. By November 1391, the new bridge appears to have been mostly finished, with the exception of the King’s drawbridge, which took until 1397 or 1398 to complete.

Meanwhile, debate continued around how the bridge was to be financially supported and maintained. John and Robert devised a plan for parishes in the old estates to take on responsibilities for parts of the cost, but this was felt to be unsustainable, and likely to encourage a tax revolt.

Instead, the decision was taken by the Crown to permit the bridge to own property up to 200 marks (£133) in value a year, rather like an abbey or similar institution.1It is difficult to accurately compare early modern financial figures with modern equivalents. See our article on medieval money for more details. After 1400, this financial endowment, created as wealthy nobles donated land to the bridge, provided all the support for the bridge. The resources were managed by two wardens of the bridge, appointed annually by the local gentry, with an element of further oversight from the the Archbishop of Canterbury. By the 1430s, there was also a bridge clerk, who provided clerical assistance.

Maintaining the bridge continued to be challenging, initially costing around £25 a year. The piers needed up to 200 fresh elm piles and around 1,000 tons of chalk to be added to the foundations each year to make good the constant damage from the fast-flowing river. The superstructure also needed ongoing repairs. The wood and chalk were drawn from an increasingly wide area around Rochester, while the old bridge was salvaged as a source of stone.

A small industry of carpenters, masons and ironworkers grew up by the bridge, to deal with the regular maintenance and the crises which occurred every twenty years or so. Rochester itself was badly affected by any periods in which the bridge was unserviceable, as traders typically took longer routes rather than risk any temporary ferry crossing. By the mid-16th century, the original 14th century bridge had been extensively rebuilt through the multiple iterations of repairs.

16th century

With advent of the Reformation, the Bridge Chapel was closed and its chantry lands were sold off in 1548. The various officials overseeing the bridge turned over in post quite quickly, and the lands owned by the bridge were financially mismanaged, probably for personal gain by the officials concerned. By the 1550s, the revenues available for maintaining Rochester Bridge were steadily reducing, and a 1557 royal commission reported that the bridge itself had “falllen into… greate ruyne and decaye”.

In 1557, Queen Mary authorised the collection of tolls on the bridge, and a gate on the Rochester side of the bridge was constructed to control access. The maladministration continued, however, and the initial boost from the toll revenues fell away quickly. In 1561, Queen Elizabeth appointed a commission to address the problem, which concluded that £2,000 of repairs were necessary: special taxes were levied across Kent to raise the money. Royal commissions in 1572 and 1575, however, discovered similar problems, and concluded that the problem lay in the way that the bridge’s lands were leased out at very low rents.

In response, in 1576 Parliament passed the Rochester Bridge Act. This created a new body of two bridge wardens and twelve assistant wardens, annually elected at Rochester Castle. They had the power to collect rents – more tightly overseen than before – and to raise local taxes to support the bridge. The wardens mainly came from gentry families in Kent, and gripped the problem of maintaining the bridge. A Bridge Chamber was soon constructed alongside the chapel for the wardens to base their work from. In 1618, the wardens had the royal beasts of James I carved and mounted above the royal drawbridge, although vandalism subsequently proved a problem.

17th-18th centuries

During the first English civil war between 1642-45, Parliament controlled most of the south-east of England. Many of the local families who had been running Rochester Bridge had Royalist sympathies, and were replaced with more reliable Parliamentarians.

The second English Civil War broke out in 1648. In May, Royalist rebels seized sites across the south-east of England, including Rochester. The bridge’s gates were shut and two guns were placed on the bridge itself. A Parliamentary regiment marched on Rochester, where the Battle of Rochester Bridge took place on 1 June.

The rebels retreated into the city, drew up the drawbridge on the bridge, and added another two guns onto the bridge. Another 40 guns supported the bridge from along the river bank, along with two ships, the Swallow and the Rainbow. The Parliamentary forces attacked the position but, after heavy fighting, they were forced to withdraw.

Meanwhile, the Royalist army had been defeated at the Battle of Maidstone and the rebels at Rochester decided to withdraw back towards Essex. They broke up the drawbridge before they went, and threw the pieces into the river. After the conflict had finished, the bridge wardens paid two men 1s and 6d to pull the remains of the bridge out again. With the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, the pro-Parliamentary members of the bridge warden team were purged, and replaced by Royalist supporters.

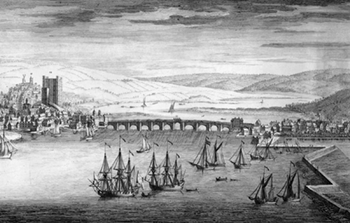

In the late 17th and 18th centuries, Rochester prospered from increasing international trade and the growing naval presence at the Chatham dockyards. The Medway valley became all the more important as a trade route, but Rochester Bridge had become a barrier to river traffic. Its wood and chalk starlings blocked much of the river, pushing the water through the remaining gaps at speed – accidents were common, and boats and barges often hit the bridge, damaging its foundations. Its arches were also now too low, and blocked many larger boats from passing.

By early 18th century, around ten craftsmen and labourers were kept employed at the bridge, working mainly during the summer months. Major repairs carried out between 1736 and 1741, requiring a much larger team, and efforts were made to improve the oversight processes. A broader range of people began to serve as bridge wardens, including industrialists and professionals, as well as the traditional representatives of the gentry. The bridge wardens came to term themselves “the noblemen and gentlemen of Rochester Bridge”.

19th- 21st centuries

By the early 19th century, reforms of the administration of Rochester Bridge were being considered. A Bill in Parliament tried, but failed, to introduce tolls, and there were conversations about the Crown possibly taking over control of the bridge. These debates were fueled by reports during the 1820s and 1830s of possible maladministration of the bridge and its assets.

Meanwhile, more radical options for the bridge itself were being put forward. In 1780, plans were drawn up to widen the bridge, and two years later proposals were put forward to reconstruct the centre of the bridge in iron, similar to the new structure being built at Ironbridge in Coalbrookdale.

Instead of these options, between 1793 and 1804 the bridge was improved and widened under the architect Daniel Alexander. The costs soon spiralled out of control to over £20,000, while the revenues available to the wardens were limited by the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars. This prevented the planned replacement of the bridge’s central arch.

By 1818, there were discussions about building an entirely new bridge. A temporary bridge was built to permit traffic to continue to cross the river. Fierce debate ensued about whether the new bridge should be stone, or in iron, or alternatively if a tall, central arch should simply be added to the existing structure. The latter option was ultimately chosen, primarily on the grounds of cost, and between 1821 and 1823 the so-called great arch was added to Rochester Bridge, under the direction of John Rennie .

The increasing volumes of traffic, the continuing impact of the starlings on river navigation, and the cost of ongoing repairs soon prompted fresh calls for the construction of an entirely new bridge. The Admiralty , in particular, noted that the bridge was causing large amounts of debris to build up at the nearby Chatham Dockyards, which was costing the government over £1,700 a year to remove. The bridge wardens began to save up money for a complete replacement, and in 1846 the Rochester Bridge Act was passed, enabling the construction work to ultimately begin.

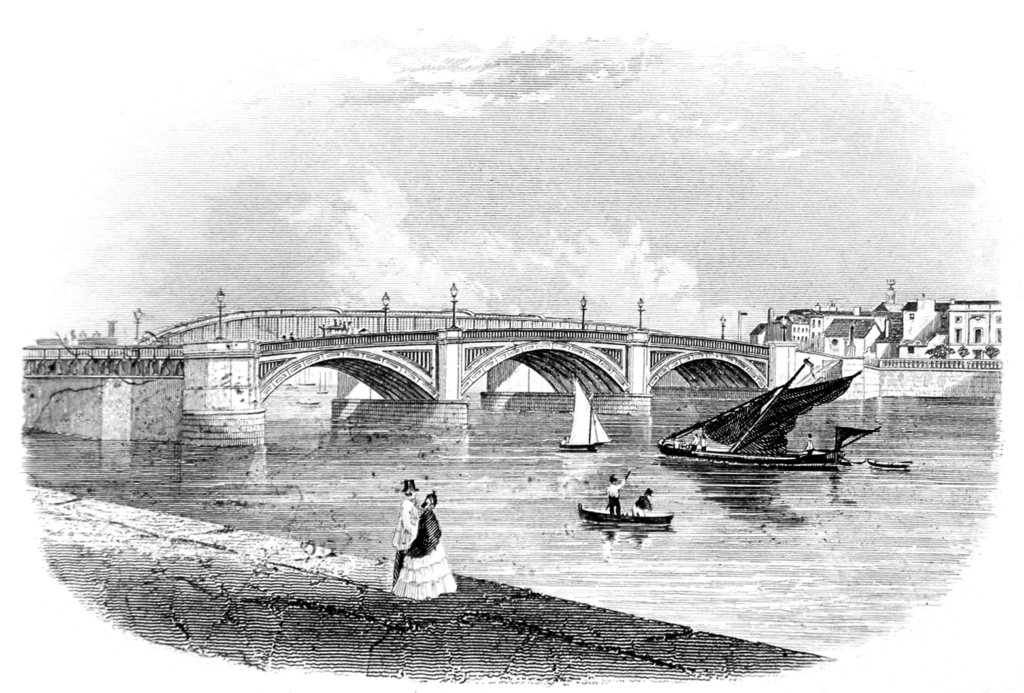

The new bridge was constructed on stone piers, with three iron arches, 140, 170 and 170 ft across respectively. The piers rested on piles forced deep into the river bed using a new industrial approach called the Potts process. There was a swing bridge, on the west side of the bridge, to allow ships to pass through. After various delays, the new bridge was formally opened in August 1856 and the old bridge was demolished, the last parts of its foundations being blown up by the Royal Engineers that November.

The swing bridge proved difficult – and expensive – to maintain, but in 1881, as plans were being made by the East Kent Railway Company to built a railway bridge just to the north, it emerged that the swing bridge had never really been used. As a result, the new railway bridge had no swing function installed, blocking the river and making the Rochester Bridge’s swing functionality pointless, and so in 1890 the swing bridge was permanently fixed in place. Gas and electricity lines were run across the bridge in the 1870s and 1880s, and a tramline was extended over it in 1902.

The new bridge proved vulnerable to accidents, with several boats hitting it in 1896 and 1907. Combined with the high costs of maintenance, this encouraged discussions of potentially reconstructing the bridge to create taller arches, leading to the Rochester Bridge Act of 1908. Work began in 1911 and was completed by 1914 at a total cost of £95,857. During the First World War, the bridge was protected by the military, complete with guard posts and barbed wire.

The pressure of road traffic grew after the Second World War, and in 1965 another Rochester Bridge Act was passed. This allowed the reconstruction of the old railway bridge to turn it into another road bridge. Work began in 1967, and the bridge was opened in 1970, becoming known as the New Bridge – the adjacent 1914 bridge being called the Old Bridge.

The bridges are still managed by the Rochester Bridge Trust, first established in the medieval period, and in daily use.

Visiting the bridge

Bibliography

- Arnold, A.A. (1887) “Rochester Bridge in A.D. 1561,” Archaeologia Cantiana Volume 17, pp. 212-240.

- Arnold, A.A. (1921) “The Earliest Rochester Bridge. Was it built by the Romans?” Archaeologia Cantiana Volume 35, pp. 127-144.

- Harrison, David Featherston. (2004) The Bridges of Medieval England: Transport and Society, 400-1800. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press.

- Yates, Nigel and James M. Gibson (eds). (1994) Traffic and Politics: The Construction and Management of Rochester Bridge, AD 43-1993. Woodbridge (UK): Boydell Press and the Rochester Bridge Trust.

Attribution

The text of this page is licensed under under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Images on this page include those drawn from the British Museum, Cambridge University and Wikimedia websites, as of 27 May 2020, and attributed and licensed as follows: adapted from “John Speed’s map of Rochester“, photograph copyright Cambridge University Library, released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-NC 3.0); “Rochester Bridge, 1738″, photograph copyright The Trustees of the British Museum, released under CC BY-ND_SA 4.0; “Rochester Bridge, 2011“, author Klovovi, released under CC BY 2.0.