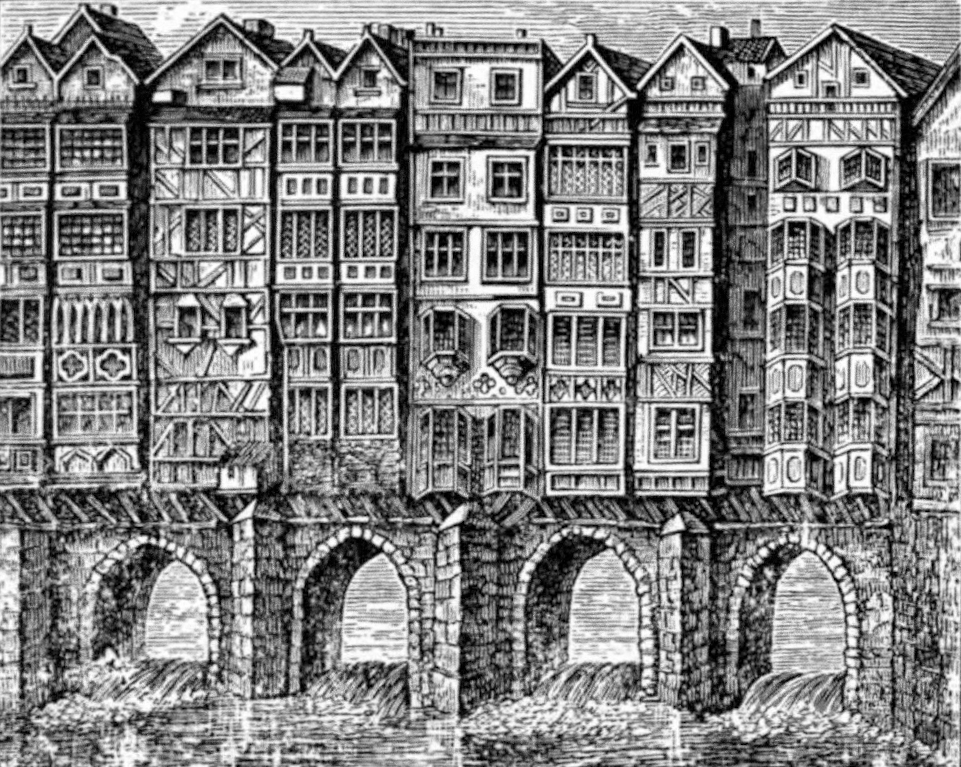

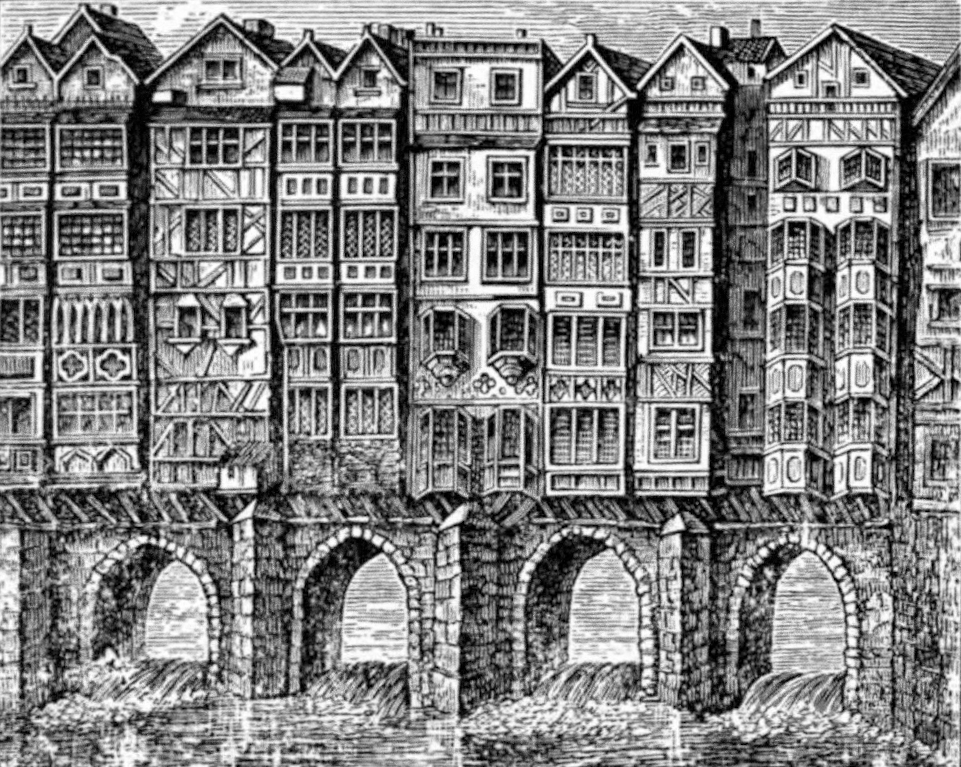

Bristol Bridge was a fortified bridge across the River Avon, built between 1247 and 1248. It replaced an earlier timber bridge on the same site, from which the surrounding city had acquired its name. In 1361 a large chapel was constructed in the middle of the bridge, forming a gatehouse. Rows of houses grew up on either side of the bridge, which became a prosperous neighbourhood.

By the 1750s, there were calls for the bridge to be replaced by a more convenient and modern alternative. The medieval bridge was pulled down in 1762 and the new Georgian bridge opened in 1768. That bridge was updated in the 1870s and remains in use today.

History

9th-14th centuries

There was probably a timber bridge in Bristol over the River Avon in the early medieval period, on the route between Somerset and Gloucestershire. Bristol means “the place of the bridge”, and probably acquired that name from this older bridge. By the late Anglo-Saxon period, the villages on the far side of the bridge probably protected the entrance into the town across the bridge, and may have been protected themselves with a substantial ditch and earthwork bank.

By the mid-13th century, Bristol was growing, incorporating the villages north of the River, while the River Frome was recut in the 1240s, creating a new port. Bristol Bridge was constructed from 1247 to 1248, linking Bristol’s older centre to its growing northern edge.

Contemporaries described the bridge as being 216 ft (65.8 m) across, and 15 ft (4.6 m) across, with four stone arches, rising in height at the centre. The superstructure was constructed from Pennant sandstone. Later surveys suggested the structure had been originally very well made and it proved relatively robust over the years.

In 1361, work on a chapel in the middle of the bridge was finished, which was dedicated to the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary. The chapel was 75 ft (22.9 m), and 21 ft (6.4 m) wide, overhanging the sides of the bridge. It had gates at either end of a covered passageway, effectively creating a large gatehouse, controlling access into the city. The ground floor formed a crypt, used as a meeting room for Bristol’s council, with the chapel on the first floor, and a bell-tower above that.

Over the course of the 14th century, houses began to be built on the edges of the bridge, often with shops at the street level, and some with cellars supported by arches underneath. Eventually, there were up to sixty houses along the bridge. During the 16th and 17th centuries, these houses grew in height to become tenement blocks, overhanging the steet below on storey posts. In the 1547, the Reformation caused the closure of the chapel; the building was initially purchased by the Bristol Corporation for £40, and rented out as warehouse.

The bridge was an affluent neighborhood, and it was relatively clean and open in what was often a heavily polluted city. It was difficult to maneuver vehicles across its cramped street, however, and accidents were common. Its low arches below also presented risks to boatmen passing along the river.

By the time of the English Civil War, in the 1640s, Bristol Bridge was known for its strong Parliamentary and Puritan sympathies, and as being a popular location for goldsmiths to operate the businesses – probably because it was more secure than most parts of the city. The inhabitants were known as the “Bridgemen”. A draper called Stephens, who was one of their leaders, demolished the chapel in 1643; in 1649, after the war, he was given permission to build houses for him and his son on the part of the site, in exchange for repairing the arches underneath.

15th-18th centuries

By the mid-18th century, there were growing pressures to redevelop the bridge, influenced in part by London’s decision to reconstruct its own medieval bridge in 1757, and by the growing trade in Bristol during the Severn Years’ War. An Act of Parliament was passed in 1760 to enable Bristol Corporation to rebuild the bridge and deshape the surrounding streets.

The replacement was designed James Bridges and built by Thomas Paty, who created a new stone bridge with three arches, paid for by tolls and local taxes. The old bridge was taken down in 1762 at a cost of £700, and a temporary wooden bridge built just along the river. After many delays, the new bridge was finally opened in late 1768.

The tolls to pay for the bridge remained unpopular, and in 1793 violence broke out, in what became known as the “Bristol Bridge Riot”. Many citizens believed that the cost of the bridge had been settled, and that the tolls would cease in September. When the Bristol Corporation announced that they would be extended to continue to pay for the debt, a mob broke down the gates on the bridge and robbed the toll houses.

The Hereford militia was called out, and around 50 militiamen confronted the crowd. They opened fire, killing 12 citizens immediately. Many others were taken for medical treatment, and contemporaries assessed that perhaps 40 died in total.

19th-21st centuries

The Georgian bridge was widened between 1873 and 1874, with the addition of Courtfeld Limestone ashlar stone, and a cast-iron deck and pillars. It remains in use, and is protected under UK law as a Grade II listed building.

Bibliography

- Baker, Nigel, Jonathan Brett and Robert Jones. (2018) Bristol: A Worshipful Town and Famous City: An Archaeological Assessment. Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK.

- Drummond, Barb. (2007) Death and the Bridge: The Georgian Rebuilding of Bristol Bridge. Barb Drummond: Bristol, UK.

- Lynch, John. (2009) Bristol and the Civil War: For King and Parliament. The History Press: Stroud, UK.

- Neale, Frances. (ed) (2000) William Worcestre: The Topography of Medieval Bristol. Bristol Record Society, Volume 51. Bristol Record Society: Bristol, UK.

- Taylor, John. *1878) Bristol and Clifton, Old and New. Houlston and Sons: London.

Attribution

The text of this page is licensed under under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Photographs on this page include those drawn from the Wikimedia and Cambridge University websites, as of 11 May 2020, and attributed and licensed as follows: “1673 Millerd Map detail” (Public Domain); adapted from “John Speed’s map of Bristol“, photograph copyright Cambridge University Library, released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-NC 3.0); “Old Bristol Bridge” (Public Domain); “Bristol Bridge, 2008“, author Andy Bebbington, released under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.