Stokesay Castle is a fortified manor house in Stokesay, Shropshire. It was built in the late 13th century by Laurence of Ludlow, then the leading wool merchant in England, who intended it to form a secure private house and generate income as a commercial estate. Laurence’s descendants continued to own the castle until the 16th century, when it passed through various private owners. By the time of the outbreak of the English Civil War in 1641, Stokesay was owned by William Craven, the first Earl of Craven and a supporter of King Charles I. After the Royalist war effort collapsed in 1645, Parliamentary forces besieged the castle in June and quickly forced its garrison to surrender. Parliament ordered the property to be slighted, but only minor damage was done to the walls, allowing Stokesay to continue to be used as a house by the Baldwyn family until the end of the 17th century.

In the 18th century the Baldwyns rented the castle out for a range of agricultural and manufacturing purposes. It fell into disrepair, and the antiquarian John Britton noted during his visit in 1813 that it had been “abandoned to neglect, and rapidly advancing to ruin”. Restoration work was carried out in the 1830s and 1850s by William Craven, the second Earl of Craven. In 1869 the Craven estate, now heavily in debt, was sold to the wealthy industrialist John Derby Allcroft who paid for another round of extensive restoration during the 1870s. Both of these owners attempted to limit any alterations to the existing buildings during their conservation work, which was unusual for this period. The castle became a popular location for tourists and artists, and was formally opened to paying visitors in 1908.

Allcroft’s descendants fell into financial difficulties during the early 20th century, however, and it became increasingly difficult for them to cover the costs of maintaining Stokesay. In 1986, Jewell Magnus-Allcroft finally agreed to place Stokesay Castle into the guardianship of English Heritage, and the castle was left to the organisation on her death in 1992. English Heritage carried out extensive restoration of the castle in the late 1980s. In the 21st century, Stokesay Castle continues to be operated as a tourist attraction, receiving 39,218 visitors in 2010.

Architecturally, Stokesay Castle is “one of the best-preserved medieval fortified manor houses in England”, according to historian Henry Summerson. The castle comprises a walled, moated enclosure, with an entrance way through a 17th-century timber and plaster gatehouse. Inside, the courtyard faces a stone hall and solar block, protected by two stone towers. The hall features a 13th-century wooden-beamed ceiling, and 17th-century carved figures ornament the gatehouse and the solar. The castle was never intended to be a serious military fortification, but its style was intended to echo the much larger castles being built by Edward I in North Wales. Originally designed as a prestigious, secure, comfortable home, the castle has changed very little since the 13th century, and is a rare, surviving example of a near complete set of medieval buildings. English Heritage has minimised the amount of interpretative material displayed at the property and kept the castle largely unfurnished.

History

13th – 15th centuries

Stokesay Castle was built in the 1280s and 1290s in the village of Stokesay by Laurence of Ludlow, a very wealthy wool merchant. Stokesay took its name from the Anglo-Saxon word stoches, meaning cattle farm, and the surname of the de Says family, who had held the land from the beginning of the 12th century onwards. In 1241, Hugh de Say sold Stokesay to John de Verdon; John then left for the Eighth Crusade in 1270, mortgaging the land on a life-time lease to Philip de Whichcote. John died in 1274, leaving his rights to the property to his son, Theobald.

Laurence bought Stokesay from Theobald and Philip in 1281, possibly for around £266, which he could easily have afforded, as he had made a fortune from the wool trade.1It is difficult to accurately compare early modern financial figures with modern equivalents. See our article on medieval money for more details. Laurence exported wool from the Welsh Marches, travelling across Europe to negotiate sales, and maintaining offices in Shrewsbury and London. He had become the most important wool merchant in England, helping to set government trade policies and lending money to the major nobility. Stokesay Castle would form a secure personal home for Laurence, well-positioned close to his other business operations in the region. It was also intended to be used as a commercial estate, as it was worth around £26 a year, with 120 acres (49 ha) of agricultural land, 6 acres (2.4 ha) of meadows, an expanse of woodland, along with watermills and a dovecot.

Work began on the castle at some point after 1285, and Laurence moved into his new property in the early 1290s. The castle was, as Nigel Pounds describes it, “both pretentious and comfortable”, initially comprising living accommodation and a tower to the north. In 1291 Laurence received permission from the King to fortify his castle – a document called a licence to crenellate – and he may have used this authority to construct the southern tower, which had a particularly martial appearance and was added onto the castle shortly afterwards.

In November 1294 Laurence was drowned at sea off the south of England, and his son, William, may have finished some of the final work on Stokesay. His descendants, who took the Ludlow surname, continued to control Stokesay Castle until the end of the 15th century, when it passed into the Vernon family by marriage.

16th – 17th centuries

Stokesay Castle was passed by Thomas Vernon to his grandson Henry Vernon in 1563. The family had hopes of becoming members of the peerage and, possibly as a consequence, the property began to be regularly called a “castle” for the first time during this period. Henry divided his time between London and Stokesay, probably staying in the north tower. Henry stood surety for an associate’s debts and when they defaulted, he was pursued for this money, resulting in a period of imprisonment in Fleet Prison; by 1598 he sold the castle for £6,000 to pay off his own substantial debts. The new owner, Sir George Mainwaring, sold the property on again in 1620, via a consortium of investors, to the wealthy widow and former Mayoress of London, Dame Elizabeth Craven for £13,500.2It is difficult to accurately compare early modern financial figures with modern equivalents. See our article on medieval money for more details. The estates around Stokesay were now valuable, bringing in over £300 a year in income.

Elizabeth’s son, William, spent little time at Stokesay and by the 1640s had leased it out to Charles Baldwyn, and his son Samuel. He rebuilt the gatehouse during 1640 and 1641, however, at a cost of around £533. In 1643 the English Civil War broke out between the supporters of King Charles I and Parliament. A Royalist supporter, William spent the war years at Elizabeth Stuart’s court at the Hague, and gave large sums of money to the King’s war effort. William installed a garrison in the castle, where the Baldwins were also strong Royalists, and, as the conflict progressed, the county of Shropshire became increasingly Royalist in sympathies. Despite this, by late 1644 bands of vigilante clubmen had risen up in Shropshire, complaining about the activities of Royalist forces in the region, and demanding, among other things, the removal of the garrison from Stokesay Castle.

By early 1645 the war had turned decisively against the King, and in February, Parliamentary forces seized the county town of Shrewsbury. This exposed the rest of the region to attack, and in June a force of 800 Parliamentary soldiers pushed south towards Ludlow, attacking Stokesay en route. The Royalist garrison, led by Captain Daurett, was heavily outnumbered and it would have been impossible for them to effectively defend the new gatehouse, which was essentially ornamental. Nonetheless, both sides complied with the protocols of warfare at the time, resulting in a bloodless victory for the Parliamentary force: the besiegers demanded that the garrison surrender, the garrison refused, the attackers demanded a surrender for a second time, and this time the garrison were able to give up the castle with dignity.

Shortly afterwards on 9 June, a Royalist force led by Sir Michael Woodhouse attempted to recapture the castle, now garrisoned by Parliament. The counter-attack was unsuccessful, ending in the rout of the Royalist forces in a skirmish at the nearby village of Wistanstow.

Unlike many castles in England which were deliberately seriously damaged, or slighted, to put them beyond military use, Stokesay escaped substantial harm after the war. Parliament sequestrated the property from William and ordered the slighting of the castle in 1647, but only pulled down the castle’s curtain wall, leaving the rest of the complex intact. Samuel returned in 1649 to continue to rent the castle during the years of the Commonwealth, and put in wood panelling and new windows into parts of the property. With the restoration of Charles II to the throne in 1660, William’s lands were returned to him, and the Baldwyns continued to lease Stokesay Castle from him.

18th – 19th centuries

During the 18th century, Stokesay Castle continued to be leased by the Baldwyn family, although they sublet the property to a range of tenants; after this point it ceased to be used as a domestic dwelling. Two wood and plaster buildings, built against the side of the hall, were demolished around 1800, and by the early 19th century the castle was being used for storing grain and manufacturing, including barrel-making, coining and a smithy.

The castle began to deteriorate, and the antiquarian John Britton noted during his visit in 1813 that it had been “abandoned to neglect, and rapidly advancing to ruin: the glass is destroyed, the ceilings and floors are falling, and the rains streams through the opening roof on the damp and mouldering walls”. The smithy in the basement of the south tower resulted in a fire in 1830, which caused considerable damage to the castle, gutting the south tower. Extensive decay in the bases of the cruck tresses in the castle’s roof posed a particular threat to the hall, as the decaying roof began to push the walls apart.

Restoration work was carried out in the 1830s by William Craven, the Earl of Craven. This was a deliberate attempt at conserving the existing building, rather than rebuilding it, and was a very unusual approach at this time. By 1845, stone buttresses and pillars had been added to support parts of the hall and its roof. Research by Thomas Turner was published in 1851, outlining the history of the castle. Frances Stackhouse Acton, a local landowner, took a particular interest in the castle, and in 1853 convinced William to carry out further repair work on the castle, under her supervision, at a cost of £103.3It is difficult to accurately compare early modern financial figures with modern equivalents. See our article on medieval money for more details.

In 1869 the Craven estate, 5,200 acres (2,100 ha) in size but by now heavily mortgaged, were purchased by John Derby Allcroft for £215,000. Allcroft was the head of Dents, a major glove manufacturer, through which he had become extremely wealthy. The estate included Stokesay Castle, where from around 1875 onwards Allcroft undertook extensive restoration work over several years. Stokesay was in serious need of repairs: the visiting writer Henry James noted in 1877 that the property was in “a state of extreme decay”.

Allcroft attempted what the archaeologist Gill Chitty has described as a “simple and unaffected” programme of work, which generally attempted to avoid excessive intervention. He may have been influenced by the contemporary writings of the local vicar, the Reverend James La Touche, who took a somewhat romanticised approach to the analysis of the castle’s history and architecture. The castle had become a popular sight for tourists and artists by the 1870s and the gatehouse was fitted out to form a house for a caretaker to oversee the property. Following the work, the castle was in good condition once again by the late 1880s.

20th – 21st centuries

Further repairs to Stokesay Castle were required in 1902, carried out by Allcroft’s heir, Hebert, with help from the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. The Allcroft family faced increasing financial difficulty in the 20th century and the castle was formally opened for visitors in 1908, with much of the revenue reinvested in the property, but funds for repairs remained in short supply. By the 1930s the Allcroft estate was in serious financial difficulties, and the payment of two sets of death duties in 1946 and 1950 added to the family’s problems.

Despite receiving considerable numbers of visitors – over 16,000 in 1955 – it was becoming increasingly impractical to maintain the castle, and calls were made for the State to take over the property. For several decades the owners, Philip and Jewell Magnus-Allcroft, declined these proposals and continued to run the castle privately. In 1986 Jewell finally agreed to place Stokesay Castle into the guardianship of English Heritage, and the castle was left to the organisation on her death in 1992.

The castle was passed to English Heritage largely unfurnished, with minimal interpretative material in place, and it needed fresh restoration. There were various options for taking forward the work, including restoring the castle to resemble a particular period in its history; using interactive approaches such as “living history” to communicate the context to visitors; or using the site to demonstrate restoration techniques appropriate to different periods. These were rejected in favour of a policy of minimising any physical intervention during the restoration and preserving the building in the condition it was passed to English Heritage, including its unfurnished interior. The archaeologist Gill Chitty has described this as encouraging visitors to undergo a “personal discovery of a sense of historical relationship and event” around the castle. Against this background, an extensive programme of restoration work was carried out between August 1986 and December 1989.

In the 21st century, Stokesay Castle continues to be operated by English Heritage as a tourist attraction, receiving 39,218 visitors in 2010. The castle is protected under UK law as a Grade I listed building and as a scheduled monument.

Architecture

Structure

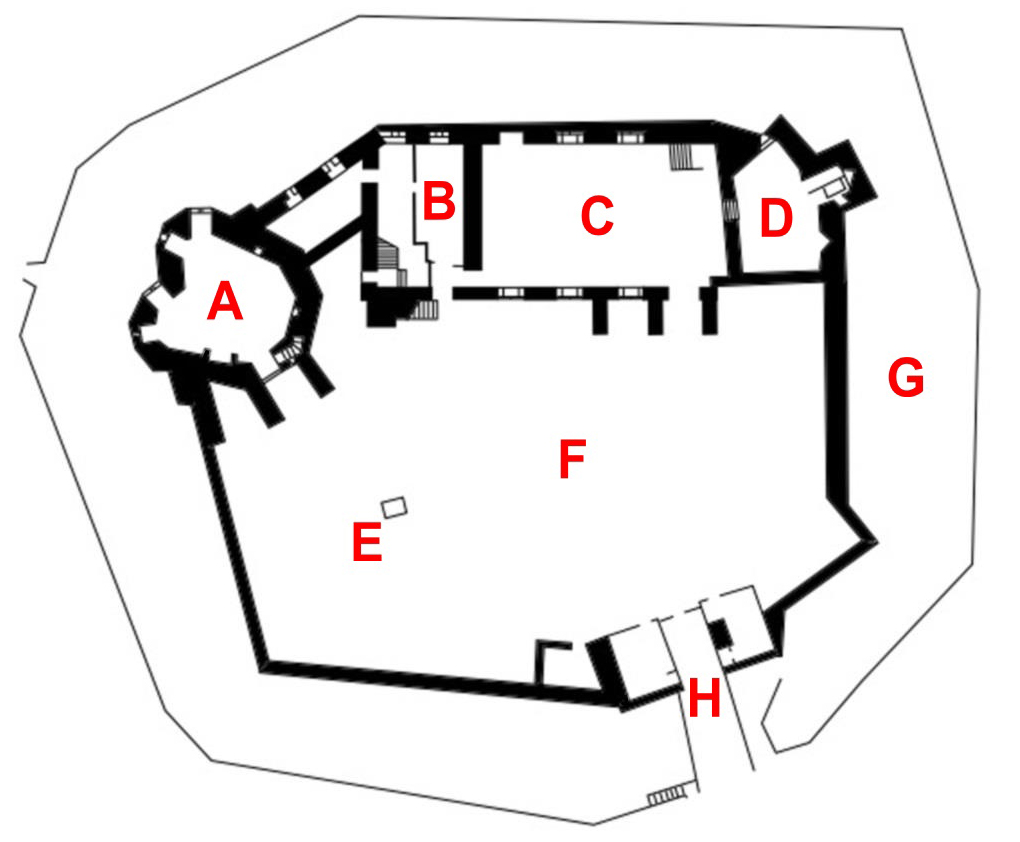

Stokesay Castle was built on a patch of slightly rising ground in the basin of the River Onny. It took the form of a solar block and hall attached to a northern and southern tower; this combination of hall and tower was not uncommon in England in the 13th century, particularly in northern England. A crenellated curtain wall, destroyed in the 17th century, enclosed a courtyard, with a gatehouse – probably originally constructed from stone, rebuilt in timber and plaster around 1640 – controlling the entrance. The wall would have reached 34 feet (10 m) high measured from the base of the moat. The courtyard, around 150 feet (46 m) by 125 feet (38 m), contained additional buildings during the castle’s history, probably including a kitchen, bakehouse and storerooms, which were pulled down around 1800.

The castle was surrounded by a moat, between 15 feet (4.6 m) and 25 feet (7.6 m) across, although it is uncertain whether this was originally a dry moat, as it is in the 21st century, or water-filled from the pond and nearby stream.4The historian Henry Summerson is doubtful about the moat having been filled with water in the 13th century, arguing that there is no surviving evidence of it having been lined with clay – which would have improved its ability to store water – and considers that archaeological excavation will be the only way to determine its original condition. Historian Robert Liddiard and the site inspector Michael Watson argue that it was water-filled, accompanying the other water features around the castle. The spoil from digging out the moat was used to raise the height of the courtyard. Beyond the moat were a lake and ponds that were probably intended to be viewed from the south tower. The parish church of St John the Baptist, of Norman origins but largely rebuilt in the middle of the 17th century, lies just alongside the castle.

Stokesay Castle forms what archaeologist Gill Chitty describes as “a comparatively complete ensemble” of medieval buildings, and their survival, almost unchanged, is extremely unusual. Historian Henry Summerson considers it “one of the best-preserved medieval fortified manor houses in England”.

Buildings

The gatehouse is a two-storied, 17th century building with exposed timber and plasterwork, constructed in a distinctively local Shropshire style. It features elaborate wooden carvings on the exterior and interior doorways, including angels, the biblical characters of Adam, Eve and the serpent from the Garden of Eden, as well as dragons and other nude figures. It was designed as essentially an ornamental building, with little defensive value.

The south tower forms an unequal pentagon in shape, and has three storeys with thick walls. The walls were built to contain the stairs and garderobes, the unevenly positioned empty spaces weakening the structure, and this meant that two large buttresses had to be added to the tower during its construction to support the walls. The current floors are Victorian in origin, having been built after the fire of 1830, but the tower remains unglazed, as in the 13th century, with shutters at the windows providing protection in winter. The basement was originally only accessible from the first floor, and would have provided a secure area for storage, in addition to also containing a well. The first floor, which formed the original entrance to the tower, contains a 17th-century fireplace, reusing the original 13th-century chimney. The second floor has been subdivided in the past, but has been restored to form a single chamber, as it would have been when first built.

The roof of the south tower provides views of the surrounding landscape; in the 13th-century protective wooden mantlets would have been fitted into the gaps of the merlons along the battlements, and during the English Civil War it was equipped with additional wooden defences to protect the garrison.

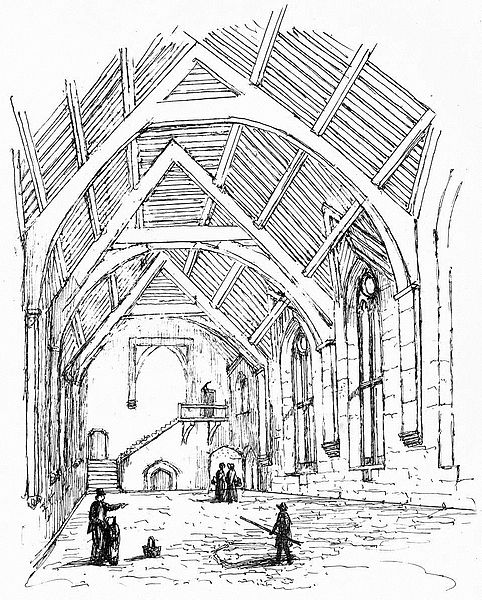

The hall and solar block are adjacent to the south tower, and were designed to be symmetrical when seen from the courtyard, although the addition of the additional stone buttresses in the 19th century has altered this appearance. The hall is 54.5 feet (16.6 m) long and 31 feet (9.4 m) wide, with has three large, wooden 13th-century arches supporting the roof, unusually, given its size, using lateral wooden collars, but no vertical king-posts. The roof’s cruck joists now rest on 19th-century stone supports, but would have originally reached down to the ground. The roof is considered by the historian Henry Summerson to be a “rare survival for the period”. In the medieval period a wooden screen would have cut off the north end, providing a more secluded dining area.

The solar block has two storeys and a cellar, and would have probably acted as the living space for Laurence of Ludlow when he first moved into the castle. The solar room itself is on the first floor, and is reached by external steps. The wood panelling and carved wooden fireplace are of 17th-century origin, probably from around 1640. This woodwork would have originally been brightly painted, and included spy-holes so that the hall could be observed from the solar.

The three-storey north tower is reached by a 13th-century staircase in the hall, which leads onto the first floor. The first floor was divided into two separate rooms shortly after the construction of the tower, and contain various decorative tiles, probably from Laurence’s house in Ludlow. The walls of the second floor are mostly half-timbered, jettying out above the stone walls beneath them; the tower has its original 13th-century fireplace, although the wooden roof is 19th-century, modeled on the 13th-century original, and the windows are 17th-century insertions. The details and the carpenters’ personal marks on the woodwork show that the hall, solar and north tower were all constructed under the direction of the same carpenter in the late 1280s and early 1290s.

Interpretation

Stokesay Castle was never intended to be a serious military fortification. As long ago as 1787, the antiquarian Francis Grose observed that it was “a castellated mansion rather than a castle of strength”, and more recently the historian Nigel Pounds has described the castle as forming “a lightly fortified home”, providing security but not intended to resist a military attack. The historian Henry Summerson describes its military features as “superficial”, and Oliver Creighton characterises Stokesay as being more of a “picturesque residence” than a fortification.

Among its weaknesses were the positioning of its gatehouse, on the wrong side of the castle, facing away from the road, and the huge windows in the hall, reaching down to the ground and making access relatively easy to any intruder. Indeed, this vulnerability may have been intentional. Its builder Laurence was a newly-moneyed member of the upper class, and he may not have wanted to erect a fortification that would have threatened the established Marcher Lords in the region.

South tower at Stokesay (left), probably intended to emulate

the North Wales gatehouses of Caernarfon

and Denbigh Castle.

Nonetheless, Stokesay Castle was intended to have a dramatic, military appearance, echoing the castles then being built by Edward I in North Wales. Visitors would have approached the castle across a causeway, with an excellent view of the south tower, potentially framed by and reflected in the water-filled moat. The south tower was probably intended to resemble the gatehouses of contemporary castles such as Caernarfon and Denbigh, and would probably have originally shared the former’s “banded” stonework. Cordingley describes the south tower as “adding prestige rather than security”. Visitors would then have passed by the impressive outside of the main hall block, before entering the castle itself, which the historian Robert Liddiard remarks might have been an “anticlimax from the point of view of the medieval visitor”.

A nude figure

the Devil

Eve

Adam

the Serpent

and a carved fireplace.

Visiting the castle

Bibliography

- Britton, John (1814), The Architectural Antiquities of Great Britain, London, UK: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme

- Chitty, Gill (1999), “The Tradition of Historic Consciousness: The Case of Stokesay Castle”, in Chitty, Gill; Baker, David (eds.), Managing Historic Sites and Buildings, Abingdon, UK: Routledge, pp. 85–97, ISBN 978-1-135-64027-9

- Cordingley, R. A. (1963), “Stokesay Castle, Shropshire: The Chronology of its Buildings”, The Art Bulletin, 45 (2): 91–107

- Creighton, O. H. (2002), Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England, London, UK: Equinox, ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8

- Donagan, Barbara (2010), War in England 1642–1649, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-956570-2

- Hall, Michael (2010), The Victorian Country House: From the Archives of Country Life, London, UK: Aurum, ISBN 978-1-84513-457-0

- Hutton, Ronald (1999), The Royalist War Effort 1642–1646 (2nd ed.), London, UK: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-203-00612-2

- La Touche, James D. (1878), “Stokesay Castle”, Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, 1: 311–332

- La Touche, James D. (1899), “Stokesay Castle”, Archaeologia Cambrensis, 16: 299–304

- Liddiard, Robert (2005), Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500, Macclesfield, UK: Windgather Press, ISBN 0-9545575-2-2

- Manganiello, Stephen C. (2004), The Concise Encyclopedia of the Revolutions and Wars of England, Scotland and Ireland, 1639–1660, Oxford, UK: Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-5100-9

- Mackenzie, James D. (1896), The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure, 2, New York, US: Macmillan

- Pettifer, Adrian (2002), English Castles: A Guide by Counties, Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, ISBN 978-0-85115-782-5

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (2000) , The Buildings of England: Shropshire, London, UK: Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-071016-8

- Pounds, Norman John Greville (1994), The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political History, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3

- Purkiss, Diane (2006), The English Civil War: A People’s History, London, UK: Harper Perennial, ISBN 978-0-00-715062-5

- Summerson, Henry (2012), Stokesay Castle (Revised ed.), London, UK: English Heritage, ISBN 978-1-84802-016-0

- Turner, Thomas Hudson (1851), Some Account of Domestic Architecture in England, 1, Oxford, UK and London, UK: James Parker

- Wedgwood, C. V. (1970), The King’s War, 1641–1647, London, UK: Fontana History

- Wright, Thomas (1921), Historical Sketch of Stokesay Castle, Ludlow, UK: G. Woolley

Attribution

The text of this page was adapted from “Stokesay Castle” on the English language website Wikipedia, as the version dated 7 January 2019, and accordingly the text of this page is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Principle editors have included Hchc2009, and the contributions of all editors can be found on the history tab of the Wikipedia article.

Photographs on this page include those drawn from the Wikimedia and Flickr websites, as of 25 June 2020 and attributed and licensed as follows: “Stokesay Castle from the graveyard” (Public Domain); “Stokesay Castle, seen from the west“, author Richard Szwejkowski, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Stokesay, castle courtyard and parish church“, author Chris Downer, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Solar of Stokesay Castle“, author Andrew Fogg, released under CC BY 2.0; “Stokesay Castle hall, 1868” (Public Domain); “Stokesay Castle, Church and reflection“, author Row17, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Stokesay Castle plan“, author Hchc2009, released under CC BY-SA 3.0; “Stokesay Castle’s gatehouse“, author DeFacto, released under CC BY-SA 4.0; “Stokesay Castle’s solar” (Public Domain); “South Tower of Stokesay Castle” (Public Domain); “Caernarfon Castle“, author Herbert Ortner, released under CC BY-SA 3.0; “Denbigh Castle“, author Dot Potter, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Nude figure” (Public Domain); “The Devil“, author Chris Gunns, released under CC BY 2.0; “Eve“, author Chris Gunns, released under CC BY 2.0; “Adam“, author Chris Gunns, released under CC BY 2.0; “The Serpent“, author Nick Hubbard, released under CC BY 2.0; “Carved woodwork“, , author Nick Hubbard, released under CC BY 2.0.