The Device programme

Background

The Device Forts emerged as a result of changes in English military architecture and foreign policy in the early 16th century. During the late medieval period, the English use of castles as military fortifications had declined in importance. The introduction of gunpowder in warfare had initially favoured the defender, but soon traditional stone walls could easily be destroyed by early artillery. The few new castles that were built during this time still incorporated the older features of gatehouses and crenellated walls, but intended them more as martial symbols than as practical military defences. Many older castles were simply abandoned or left to fall in disrepair.

Although fortifications could still be valuable in times of war, they had played only a limited role during the Wars of the Roses and, when Henry VII invaded and seized the throne in 1485, he had not needed to besiege any castles or towns during the campaign. Henry rapidly consolidated his rule at home and had few reasons to fear an external invasion from the continent; he invested little in coastal defences over the course of his reign. Modest fortifications existed along the coasts, based around simple blockhouses and towers, primarily in the south-west and along the Sussex coast, with a few more impressive works in the north of England, but they were very limited in scale.

His son, Henry VIII inherited the throne in 1509 and took a more interventionist approach in European affairs, fighting one war with France between 1512 and 1514, and then another between 1522 and 1525, this time allying himself with Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. While France and the Empire were in conflict with one another, raids along the English coast might still be common, but a full-scale invasion seemed unlikely. Indeed, traditionally the Crown had left coastal defences to local lords and communities, only taking a modest role in building and maintaining fortifications. Initially, therefore, Henry took little interest in his coastal defences; he declared reviews of the fortifications in both 1513 and 1533, but not much investment took place as a result.

In 1533 Henry broke with Pope Paul III in order to annul the long-standing marriage to his wife, Catherine of Aragon, and remarry. Catherine was the aunt of King Charles V of Spain, who took the annulment as a personal insult. As a consequence, France and the Empire declared an alliance against Henry in 1538, and the Pope encouraged the two countries to attack England. An invasion of England now appeared certain; that summer Henry made a personal inspection of some of his coastal defences, which had recently been mapped and surveyed: he appeared determined to make substantial, urgent improvements.

Initial phase, 1539–43

Henry VIII gave instructions through Parliament in 1539 that new defences were to be built along the coasts of England, beginning a major programme of work that would continue until 1547. The order was known as a “device”, which meant a documented plan, instruction or schema, leading to the fortifications later becoming known as the “Device Forts”. The initial instructions for the “defence of the realm in time of invasion” concerned building forts along the southern coastline of England, as well as making improvements to the defences of the towns of Calais and Guisnes in France, then controlled by Henry’s forces. Commissioners were also to be sent out across south-west and south-east England to inspect the current defences and to propose sites for new ones.

The initial result was the construction of 30 new fortifications of various sizes during 1539. The stone castles of Deal, Sandown and Walmer were constructed to protect the Downs in east Kent, an anchorage which gave access to Deal Beach and on which an invasion force of enemy soldiers could easily be landed. These defences, known as the castles of the Downs, were supported by a line of four earthwork forts, known as the Great Turf Bulwark, the Little Turf Bulwark, the Great White Bulwark of Clay and the Walmer Bulwark, and a 2.5-mile (4.0 km) long defensive ditch and bank. The route inland through a gap in the Kentish cliffs was guarded by Sandgate Castle. In many cases temporary bulwarks for artillery batteries were built in during the initial stages of the work, ahead of the main stonework being completed.

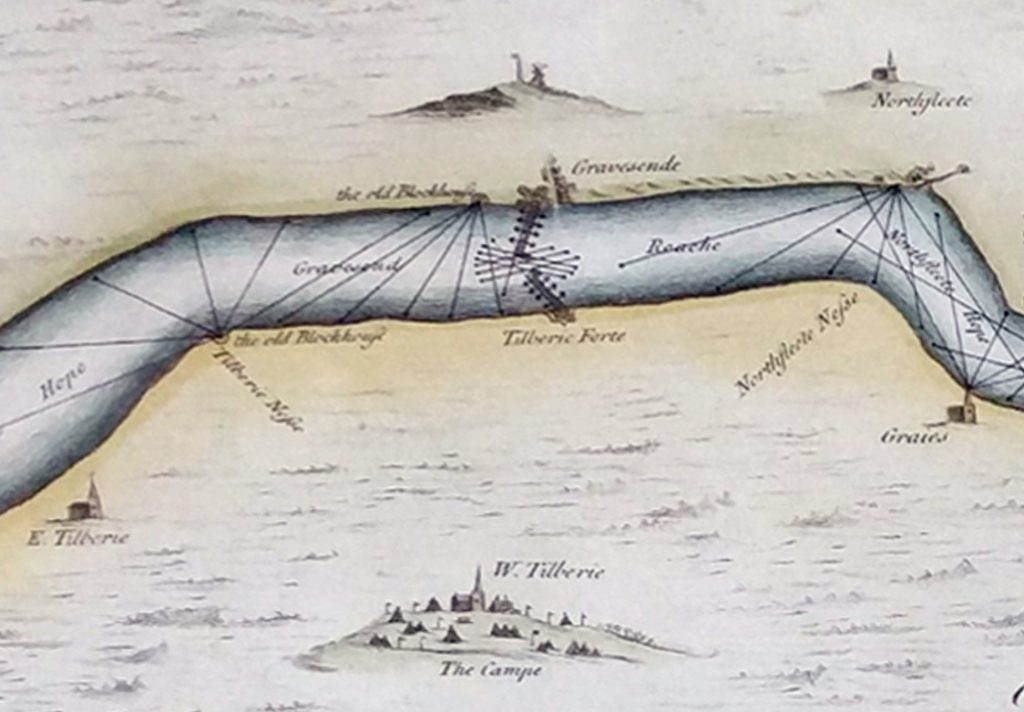

The Thames estuary leading out of London, through which 80 percent of England’s exports passed, was protected with a mutually reinforcing network of blockhouses at Gravesend, Milton, and Higham on the south side of the river, and West Tilbury and East Tilbury on the opposite bank. Camber Castle was built to protect the anchorage outside the ports of Rye and Winchelsea, defences were built in the port of Harwich and three earth bulwarks were built around Dover. Work was also begun on Calshot Castle in Fawley and the blockhouses of East and West Cowes on the Isle of Wight to protect the Solent, which led into the trading port of Southampton. The Portland Roads anchorage in Dorset was protected with new castles at Portland and Sandsfoot, and work began on two blockhouses to protect the Milford Haven Waterway in Pembrokeshire.

In 1540 additional work was ordered to defend Cornwall. Carrick Roads was an important anchorage at the mouth of the River Fal and the original plans involved constructing five new fortifications to protect it, although only two castles, Pendennis and St Mawes, were actually built, on opposite sides of the estuary. Work began on further fortifications to protect the Solent in 1541, with the construction of Hurst Castle, overlooking the Needles Passage, and Netley Castle just outside Southampton itself. Following a royal visit to the north of England, the coastal fortifications around the town of Hull were upgraded in 1542 with a castle and two large blockhouses. Further work was carried out in Essex in 1543, with a total of seven fortifications constructed, three in Harwich itself, three protecting the estuary leading to the town, and two protecting the estuary linking into Colchester. St Andrew’s Castle was begun to reinforce the Solent.

The work was undertaken rapidly, and 24 sites were completed and garrisoned by the end of 1540, with almost all of the rest finished by the end of 1543. By the time they were completed, however, the alliance between Charles and Francis had collapsed and the threat of imminent invasion was over.

Second phase, 1544–47

Henry moved back onto the offensive in Europe in 1543, allying himself with Spain against France once again. Despite Henry’s initial successes around Boulogne in northern France, King Charles and Francis made peace in 1544, leaving England exposed to an invasion by France, backed by her allies in Scotland.

In response Henry issued another device in 1544 to improve the country’s defences, particularly along the south coast. Work began on Southsea Castle in 1544 on Portsea Island to further protect the Solent, and on Sandown Castle the following year on the neighbouring Isle of Wight. Brownsea Castle in Dorset was begun in 1545, and Sharpenrode Bulwark was built opposite Hurst Castle from 1545 onwards.

The French invasion finally emerged in 1545, when Admiral Claude d’Annebault crossed the Channel and arrived off the Solent with 200 ships on 19 July. Henry’s fleet made a brief sortie, before retreating safely behind the protective fortifications. Annebault landed a force near Newhaven, during which Camber Castle may have fired on the French fleet, and on 23 July they landed four detachments on the Isle of Wight, including a party that took the site of Sandown Castle, which was still under construction. The French expedition moved further on along the coast on 25 July, bringing an end to the immediate invasion threat. Meanwhile, on 22 July the French had carried out a raid at Seaford, and Camber Castle may have seen action against the French fleet.

A peace treaty was agreed in June 1546, bringing an end to the war. By the time that Henry died the following year, in total the huge sum of £376,000 had been spent on the Device projects.1It is difficult to accurately compare early modern financial figures with modern equivalents. See our article on medieval money for more details.

Architects and engineers

Some of the Device Forts were designed and built by teams of English engineers. The master mason John Rogers was brought back from his work in France and worked on the Hull defences, while Sir Richard Lee, another of the King’s engineers from his French campaigns, may have been involved in the construction of Sandown and Southsea; the pair were paid the substantial sums of £30 and £36 a year respectively.2It is difficult to accurately compare early modern financial figures with modern equivalents. See our article on medieval money for more details. Sir Richard Morris, the Master of Ordnance, and James Needham, the Surveyor of the King’s Works, led on the defences along the Thames. The efforts of the Hampton Court Palace architectural team, under the leadership of the Augustinian canon, Richard Benese, contributed to the high-quality construction and detailing seen in many of Henry’s Device projects.

Henry took a close interest in the design of the fortifications, sometimes overruling his technical advisers on particular details. Southsea Castle, for example, was described by the courtier Sir Edmund Knyvet as being “of his Majesty’s own device”, which typically indicated that the King had taken a personal role in its design. The historian Andrew Saunders suspects that Henry was “probably the leading and unifying influence behind the fortifications”.

England also had a tradition of drawing on expert foreign engineers for military engineering; Italians were particularly sought after, as their home country was felt to be generally more technically advanced, particularly in the field of fortifications. One of these foreign engineers, Stefan von Haschenperg from Moravia, worked on Camber, Pendennis, Sandgate and St Mawes, apparently attempting to reproduce Italian designs, although his lack of personal knowledge of such fortifications impacted poorly on the end results. Technical treatises from mainland Europe also influenced the designers of the Device Forts, including Albrecht Dürer’s Befestigung der Stett, Schlosz und Felcken which described contemporary methods of fortification in Germany, published in 1527 and translated into Latin in 1535, and Niccolò Machiavelli’s Libro dell’art della guerra, published in 1521, which also described new Italian forms of military defences.

Architecture

The Device Forts represented a major, radical programme of work; the historian Marcus Merriman describes it as “one of the largest construction programmes in Britain since the Romans”, Brian St John O’Neil as the only “scheme of comprehensive coastal defence ever attempted in England before modern times”, while Cathcart King likened it to the Edwardian castle building programme in North Wales.

Although some of the fortifications are titled as castles, historians typically distinguish between the character of the Device Forts and those of the earlier medieval castles. Such castles were private dwellings as well as defensive sites, and usually played a role in managing local estates; Henry’s forts were organs of the state, placed in key military locations, typically divorced from the surrounding patterns of land ownership or settlements. Unlike earlier medieval castles, they were spartan, utilitarian constructions. Some historians such as King have disagreed with this interpretation, highlighting the similarities between the two periods, with the historian Christopher Duffy terming the Device Forts the “reinforced-castle fortification”.

The forts were positioned to defend harbours and anchorages, and designed both to focus artillery fire on enemy ships, and to protect the gunnery teams from attack by those vessels. Some, including the major castles, including the castles of the Downs in Kent, were intended to be self-contained and able to defend themselves against attack from the land, while the smaller blockhouses were primarily focused on the maritime threat. Although there were extensive variations between the individual designs, they had common features and were often built in a consistent style.

The larger sites, such as Deal or Camber, were typically squat, with low parapets and massively thick walls to protect against incoming fire. They usually had a central keep, echoing earlier medieval designs, with curved, concentric bastions spreading out from the centre. The main guns were positioned over multiple tiers to enable them to engage targets at different ranges. There were far more gunports than there were guns held by the individual fortification. The bastion walls were pierced with splayed-gun embrasures, giving the artillery space to traverse and enabling easy fire control, with overlapping angles of fire. The interiors had sufficient space for gunnery operations, with specially designed vents to remove the black powder smoke generated by the guns. Moats often surrounded the sites, to protect against any attack from land, and they were further protected by what the historian B. Morley describes as the “defensive paraphernalia developed in the Middle Ages”: portcullises, murder holes and reinforced doors. The smaller blockhouses took various forms, including D-shapes, octagonal and square designs. The Thames blockhouses were typically protected on either side by additional earthworks and guns.

These new fortifications were the most advanced in England at the time, an improvement over earlier medieval designs, and were effective in terms of concentrating firepower on enemy ships. They contained numerous flaws, however, and were primitive in comparison to their counterparts in mainland Europe. The multiple tiers of guns gave the forts a relatively high profile, exposing them to enemy attack, and the curved surfaces of the hollow bastions were vulnerable to artillery. The concentric bastion design prevented overlapping fields of fire in the event of an attack from the land, and the tiers of guns meant that, as an enemy approached, the number of guns the fort could bring to bear diminished.

Some of these issues were addressed during the second Device programme from 1544 onwards. Italian ideas began to be brought in, although the impact of Henry’s foreign engineers seems to have been limited, and the designs themselves lagged behind those used in his French territories. The emerging continental approach used angled, “arrow-head” bastions, linked in a line called a trace italienne, to provide supporting fire against any attacker. Sandown Castle on the Isle of Wight, constructed in 1545, was a hybrid of traditional English and continental ideas, with angular bastions combined with a circular bastion overlooking the sea. Southsea Castle and Sharpenode Fort had similar, angular bastions. Yarmouth Castle, completed by 1547, was the first fortification in England, to adopt the new arrow-headed bastion design, which had further advantages over a simple angular bastion. Not all the forts in the second wave of work embraced the Italian approach however, and some, such as Brownsea Castle, retained the existing, updated architectural style.

Bibliography

Attribution

The text of this page was adapted from “Device Forts” on the English language website Wikipedia, as the version dated 30 July 2018, and accordingly this page is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Principle editors have included Hchc2009, 157.203.42.132 and Nev1, and the contributions of all editors can be found on the history tab of the Wikipedia article.

Photographs on this page include those drawn from the Wikimedia website, as of 22 July 2018, and attributed and licensed as follows: “Hans Holbein, the Younger, Around 1497-1543 – Portrait of Henry VIII of England” (Public Domain); “Deal Castle Aerial View“, author Lievens Smits, released under CC BY-SA 3.0; “Southsea castle from the east“, author Geni, released under CC BY-SA 3.0; “Yarmouth Castle, Isle of Wight“, author Christine Matthews, released under