FitzHarris Castle was a small Norman castle in Abingdon, constructed between 1071 and 1081 in the wake of the Conquest. In 1247, it played a part in a well-documented struggle between Hugh Fitz-Harry and Abingdon Abbey for control of the surrounding manor. Today, only earthworks survive.

History

11th-12th centuries

FitzHarris Castle was built between 1071 and 1084, by a minor Norman lord called Oin, or Owen. Owen probably arrived in England with William the Conqueror in 1066, and was rewarded with lands at Hull in Warwickshire and in Abingdon, which he held from Abingdon Abbey.

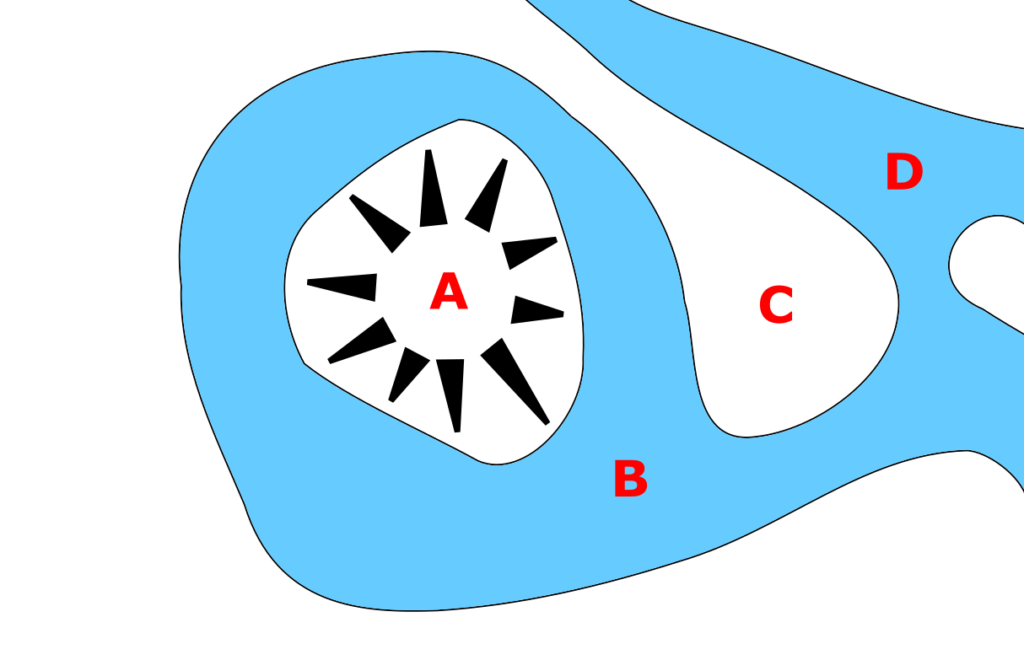

The castle was quite small, comprising a motte surrounded by a moat. When measured in the 1930s, the motte was 78 by 68 feet (24 by 21 m) across, and approximately 10 feet (3.0 m) high. Originally the moat would have been fed by water from a nearby stream. A area of land just to the east, protected by the stream, may have formed a small bailey.

13th century

Owen’s lands near Abingdon eventually became a manor of around 45 acres (18 ha) on the edge of the settlement. The manor remained in Owen’s family and, by the 1240s, they were owned by his descendant, Hugh Fitz-Harry. Although there was now a large manor house where Fitz-Harry normally lived, the castle was still defensible.

In 1247, there was a major dispute around the ownership of the castle between Fitz-Harry and the abbey. The events were recorded at the time, but probably by Walter, the prior of the abbey, and for that reason the account should not be regarded as being entirely neutral.

The abbey’s account describes Fitz-Harry as an unpopular lord, who had unfairly exploited his feudal right to impound any loose farm animals and fine their owners. Fitz-Harry eventually decided to become a crusader, associating himself with the Templar Order, and put his lands up for sale.

Fitz-Harry’s estates proved a popular prize, and the wealthy noble, Richard, Earl of Cornwall, was keen to acquire them. The abbey made a deal with Fitz-Harry, however, to buy them for almost 1,000 marks,1It is difficult to accurately compare early modern financial figures with modern equivalents. See our article on medieval money for more details. throwing in a chaplain for Fitz-Harry and provision for his son for the rest of his life. The abbey would pay 300 marks of that sum up front at the Feast of St Michael, and the rest the following year. If the money was not paid, then the agreement would be null and void.

Fitz-Harry appears to have second thoughts, as he held a great feast for his friends and supporters and, when the Prior came to pay the initial 300 marks and take possession of the estate, they barricaded themselves in the castle and refused to let him in. Negotiations ensued with the abbey’s spokesman, the Rector of Wytham, and eventually Fitz-Harry backed down. He agreed to leave the castle, along with his friends and their feast, and accept the money.

14th-21st centuries

The castle fell out of use in subsequent years, but the manor was rented out by the abbey. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s, ownership passed to the town, who continued to rent it out. The manor house was rebuilt in the 16th century, and expanded again in the 19th century. The earthworks of the castle may have been used as an ice house.

The Borough of Abingdon sold the manor in 1862, and the farmland was slowly developed for housing. Major-General Sir Charles Corkran owned the property in the 1930s, when the archaeologist A. E. Preston surveyed the castle. The manor house was demolished in 1953.

FitzHarris Castle survives in the center of a housing estate, and was commemorated with a civic plaque in 2003. It is protected under UK law as a Scheduled Monument, but was repeatedly placed on English Heritage and later Heritage England’s list of “buildings at risk” in the 2010s.

Bibliography

- Preston, A. E. (1934) “A moated mound at Abingdon, Berks,” Antiquaries Journal, Volume 14, pp. 417-421.

Attribution

The text of this page is licensed under under CC BY-NC 2.0.