Codnor Castle is a ruined fortification in Derbyshire, dating from around 1200. The castle was built in two phases, the first under Henry de Grey, who acquired the estate at the end of the 12th century and constructed the northern end of the structure in stone. Around 1320, his descendants developed the southern part of the castle, doubling its size.

The Zouch family acquired the castle in 1496 and modernised it in a Tudor style. They soon began to suffer from financial difficulties, and ultimately sold the castle on in 1634. Codnor Castle was left to fall into ruin, with many of its walls robbed for stone. In the 21st century, the castle is owned by UK Coal Mining but is run by the Codnor Castle Heritage Trust and is open to visitors.

History

11th-13th centuries

In the Anglo-Saxon period, Codnor was probably the administrative centre of a surrounding estate. In 1066, the Normans conquered England – William Peverel, a follower of William the Conqueror, was richly rewarded for supporting him during the invasion, and received lands across the north of England. Codnor became part of the Honour of Peveril, a grouping of feudal estates across the region, managed from Peveril Castle.

The Peverels held Codnor through a sequence of sub-tenants until 1154, when Henry II confiscated their lands following the poisoning of Ranulf, Earl of Chester. Towards the end of the century, Henry de Grey, a minor nobleman from Essex, married Isolde, who had inherited Codnor. Henry enjoyed royal favour and built up various lands until he died around 1220, but Isolde lived on until 1246.

By the time that Henry and Isolde took control of Codnor, there was probably a building on the northern end of the castle site, marked by a raised platform of earth. This may well have been a manor house, perhaps marking the center of the old Anglo-Saxon administration of the estate. It is not impossible that there was a small motte-and-bailey castle on the site, although no clear evidence survives to prove this. There was a deer park, later called Codnor Park, next to the site.

Henry redeveloped the site soon after he acquired it, effectively founding Codnor Castle. The castle occupied the upper part of the site, protected by a curtain wall, round towers, gatehouse and a moat, which was probably water-filled. Gardens and probably an orchard or a vineyard probably lay to the west.

The family prospered, with Codnor becoming the centre of a larger set of lands, called the Honour of Codnor. In 1293, King Edward I briefly visited the castle, and six years later Henry’s great-grandson was made a baron, Lord Grey of Codnor.

14th-15th centuries

Henry and Richard, the 2nd and 3rd Lords Grey, fought for Edward III as career soldiers in Scotland and France, enjoying royal favour and acquiring more lands. The King visited Codnor Castle in 1322. Backed by their growing financial security, around this time the family redeveloped the castle.

A residential block and probably other buildings were added along the inside curtain wall and new gardens built on the north side of the castle, overlooked by the new apartments. Although much of the moat was filled in to accommodate this work, the appearance of the gatehouse itself was strengthened with a drawbridge. At some point, probably at this time, a walled lower court was added to the castle, separated by the remains of the moat. The castle was surrounded by parkland, which would have been used for hunting.

Codnor Castle continued to be owned by the Greys throughout the 14th and 15h centuries, with a brief exception in the early 1440s. Henry, the 6th Lord Grey, found himself in trouble with the Crown for fighting with his rival Richard Vernon, and leased Codnor and various other manors to the Duke of Gloucester and a group of other nobles for five years. Henry’s son, another Henry, probably began mining and ironworking around Codnor, before his death without heirs in 1496.

16th-17th centuries

Codnor Castle and the Grey estates passed by a complex sequence of transactions to John Zouch, a younger son of a Northamptonshire gentry family. John and his descendents held the property for the next century.

Around 1500, the Zouches carried out some modernisation of the castle in the contemporary style, installing larger windows and bigger fireplaces. A new set of gardens were built on the east side of the moat, again in a contemporary Tudor style, but were probably never entirely finished.

The Zouch family were increasingly involved in the growing mining and ironworking around the region, but money problems were rarely far away, and by the 1590s they were in serious financial difficulties. After the antiquarian John Leland visited the castle in the 1540s, he described it as “ruinous”. The main residential block appears to have been abandoned during the period, possibly due to the cost of maintaining it, although smaller buildings remained occupied. The park was broken up for agricultural use.

The last Zouch to live at Codnor, another John Zouch, inherited a near-bankrupt estate. In 1634, John sold the estate to Richard Neile, the Bishop of York, and emigrated to North America.

The now-ruined castle began to be robbed for stone for local houses. A farm house – now Castle Farm – was built alongside it in 1640s. The estate was used for industrial purposes over the next few centuries, with some open-cast mining taking place. In 1692, the colonial administrator Sir Streynsham Masters purchased the castle and the surrounding estate.

18th-21st centuries

By the end of the 18th century, the surrounding area became increasingly industrialised. The mineral rights under the castle were leased out in 1790, and foundry furnaces constructed nearby. Part of the inner court were dug up in a search for iron stone in the 1850s, and in 1862, the estate was purchased by the iron-working Butterley Company.

In 1965, the District Council blocked proposals to demolish the ruins, although the castle’s medieval dovecote was pulled down. After a brief period in private ownership, the estate was purchased by the National Coal Board, and is now owned by UK Coal Mining.

The Codnor Castle Heritage Trust was formed in 2006 to manage the site and open it to visitors. Archaeological investigations followed in 2007 through Channel 4’s Time Team television programme, and the next year UK Coal Mining carried out consolidation of the ruins. The castle is now protected under law as Grade II listed building and as a Scheduled Ancient Monument.

Architecture

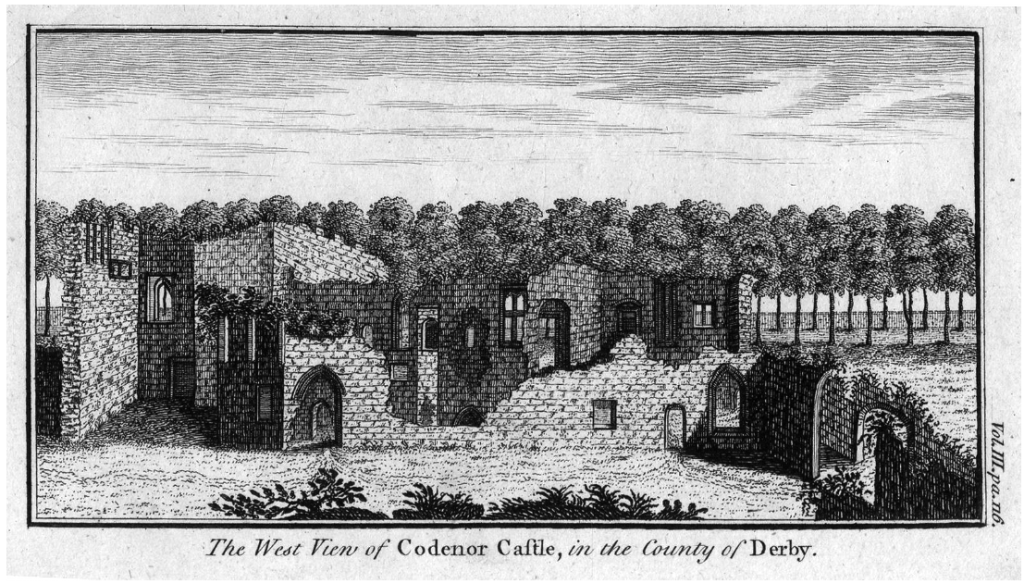

The remains of the castle today comprise the upper and lower courts, and earthworks that formed the various castle gardens.

The upper court is approximately 50 by 30 metres (164 by 98 ft) in size, bounded by a sandstone curtain wall. The entrance is flanked by two bastions, with two round towers surviving on either corner. There were probably originally bastions on the west and east walls, and two more towers along the north side. Parts of the two-storey high 14th century accommodation block survive in the north-east corner.

It is unclear where the occupants drew their water from, as the site is now dry and there is no sign of a well. Mining has reduced the height of the local water table, and it is probable that there would originally have been a natural spring in the north-west corner of the castle moat.

The original moat around the upper court survives in places, although some of it was backfilled during the medieval periods or by more recent stone falls. The moat is now dry, but would probably originally have been wet.

The lower court was probably approximately 50 by 30 metres (164 by 98 ft) in size. It was originally bounded by a 14th-century curtain wall, of which parts survive on the western side; the wall on the eastern side is of a later date, probably from when the court was extended in width on that side by an additional 5 to 10 metres (16 to 33 ft). There would probably have been a gatehouse on the southern side of the court that would have formed the main entrance to the later castle. Farm buildings now occupy the southern and south-eastern corner of the former court.

Various phases of gardens and orchards survive as earthworks to the west, north and east of the castle. There was once a medieval dovecote 50 m (164 ft) southwest of the site, a large building with space for 400 birds, but this was destroyed in the 1960s. There was also a large pond next to the dovecote, but this emptied as the water levels fell. Records also suggest that two local mills were associated with the castle. Dovecoates, fishponds and mills were all important symbols of lordship in the medieval period, and would have been key parts of the landscape for any visitors to the castle to appreciate.

Visiting the castle

Bibliography

- Alexander, Magnus and Jonathon Millward. (2008) Codnor Castle, Derbyshire: Earthwork Analysis: Survey Report. English Heritage Research Department report series 82/2008. Portsmouth, UK: English Heritage.

- Birbeck, Vaughan. (2009) “Investigations at Codnor Castle, Derbyshire,” Derbyshire Archaeological Journal Volume 129 pp.187-194.

- Emery, Anthony. (2000) Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, Volume 2: East Anglia, Central England and Wales. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Wessex Archaeology. (2008) Codnor Castle Derbyshire Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results. Salisbury, UK: Wessex Archaeology.

Attribution

The text of this page is licensed under under CC BY-NC 2.0.

The images included on this page include those drawn from the Wikimedia and British Museum websites, as of 9 May 2020, and attributed and licensed as follows: “Codnor Castle accommodation block“, author SteveP2008, released under CC BY 2.0; “Codnor Castle curtain wall and tower“, author SteveP2008, released under CC BY 2.0; “Lower ward“, author SteveP2008, released under CC BY 2.0; “West view of Codnor Castle“, photograph copyright The Trustees of British Museum, released under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.