Dover’s town walls were a system of fortifications constructed in the early 13th century, protecting large parts of the strategically important port. The walls were expanded after 1370 to include new neighbourhoods of the growing town and reached their maximum extent in the 15th century. They later fell into decline and by the 1530s were in ruin. Gradually dismantled between the late 17th and early 19th centuries, none of the walled circuit now survives.

History

Background

In the Anglo-Saxon period, Dover was an important trading town, with a market and a mint for striking coins. William the Conqueror moved quickly to take the town after the Battle of Hastings in 1066, and he constructed a castle high on the cliffs, on the site of the old Roman fort. The Domesday Book records that the town had the duty of providing twenty ships and crew for the King for fifteen days each year. Nonetheless, Dover was not an ideal location for embarking for France or Normandy, for which the ports of Southampton and Portsmouth were preferred.

The port became more important under King Stephen’s reign, when it linked England with Boulogne, which Stephen’s queen, Matilda had inherited. Dover was continually threatened by counts of Boulogne and Flanders, who held lands just across the Straits of Dover.

But Dover’s rise to prominence was closely linked to Henry II and the Becket affair. Knights loyal to Henry murdered Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, in 1170, and Becket was canonised soon afterwards. In 1179, Louis VII of France then took an pilgrimage to Canterbury with his sick son, hoping for a cure by praying at Becket’s tomb. Louis arrived unexpectedly at in Kent, where he was met by Henry on the beach, before progressing to Canterbury.

Henry realised that Dover Castle was unsuitable as a residence for what might become a steady flow of senior visitors to Canterbury. He spent huge sums of money rebuilding the castle, complete with a chapel dedicated to Becket. The surrounding town continued to grow in importance over the next few centuries.

Construction

There may have been a town wall in Dover by the start of the 13th century, partially enclosing the town. There are definite references to a wall from 1231 onwards. For most of the medieval period, the key harbour was on the east side of the town, until the silting up of the harbour and the retreat of the sea caused a move to the western edge. The first walls probably protected the probably protecting the southern flank of the town, towards the sea, and traced west inland.

A murage grant was given to the town by the Crown in 1324, apparently for the first time, enabling them to levy taxes to construct defences. Tolls were levied on travellers and ships visiting the harbour, as wells as taxes on landowners who owned properties next to the walls.

Further murage grants were regularly approved between 1350 and 1483, enabling the expansion of the defences to include new parts of the growing town in 1370. Snargate tower was probably renovated in 1427, with a portcullis added to the gateway, and a “gret gunne” and other ordinance were mounted on Snargate and Boldware Gate.

Decline

In the late 15th century, the town walls fell into decline. By the time that the antiquarian John Leland visited Dover in the 1530s, he could report that “the towne on the front toward the se hath bene right strongly walled and embattled, and almost al the residew; but now yt is partly fawlen downe and broken down.”

The walls and their towers were gradually demolished in the post-medieval period. Snargate was pulled down in 1682, Boldware and Biggin Gate in 1762, Cowgate in 1776, and Butchery Gate in 1819. In the 21st century, none of Dover’s walls survive.

Architecture

The walls formed a circuit across on the west side of the river, encircling around 5 ha (16 acres), with another line stretching out along the southern edge of the settlement towards the castle, protecting the front of the river valley. It is unlikely that the eastern parts of the town, overlooked by the castle, were ever fully protected by the walls.

Historians of Dover usually listed the towers along the walls in sequence, starting in the south-east corner of the main circuit with Butchery Gate, also known as Standfast Tower. The tower stood over the River Dour, and was adjacent to the butcher’s quarter, from which it took its name. Moving clockwise along the walls, Boldware Gate, later called Severus Gate, was next to a site known as “the Bench”, where Dover merchants traditionally met, and formed a large, impressive gatehouse.

Old Sar Gate originally formed the south-west corner of the walls, and possibly took its name from a device to stop debris flowing into the harbour. The new, larger Snar Gate, built when the walls were expanded, formed the new corner tower to its west, providing a sizeable entrance to Snargate Street, then a fast growing town precinct. The new circuit led onto Adrian’s Gate, also known as Upwall Gate.

The northern-west corner of the walled circuit held Cow Gate, probably named because of the pastures on the other side of the gate, and St Martin, or Monk’s Gate, part of the St Martin-le-Grand’s church. The north-east corner of the walled town was accessed through Biggin Gate, which led to Canterbury. It was impressively designed and probably intended to host ceremonial entrances and other civic events.

The circuit led onto three towers, one of them named Tynker’s Tower, and finally Fisher’s Gate – also known as Segate – where the south-east corner of the main walls met the southern line. This part of the circuit led to Cross Gate, also known as St Helen’s Gate, named after a cross above the entrance. The last tower was East Brooke Gate, which guarded the entrance to the early harbour. The wall then continued up to the cliffs under the castle.

A watchtower was constructed at Archcliffe, on the Western Heights, on the opposite side of the town to Dover Castle. It was later adapted to become an artillery fort under Henry VIII.

Bibliography

- Creighton, O.H. and Higham, R.A. (2005) Medieval Town Walls. Stroud, UK: Tempus.

- Salter, Mike. (2013) Medieval Walled Towns. Malvern, UK: Folly Publications.

- Sheila Sweetinburgh (2004) “Wax, Stone and Iron: Dover’s Town Defences in the late Middle Ages”. Archaeologia Cantiana, Volume 124, pp.183-208.

Attribution

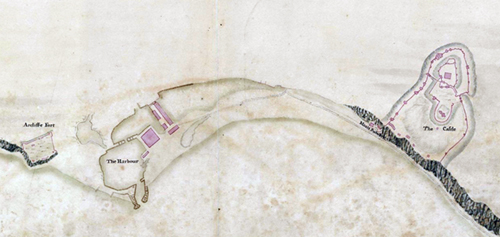

The text of this page is licensed under under CC BY-NC 2.0. Images on this page include those from the British Library, licensed as follows: Map of Dover harbour, 1552 (Public Domain); Map of Dover Harbour, 1725 (Public Domain).