Wolvesey Castle, also known as Wolvesey Palace or the Old Bishop’s Palace, was a fortified palace owned by the bishops of Winchester, constructed during the course of the 12th century within the bounds of the walled city. It was one of the greatest buildings of its time.

The castle was built on an older Anglo-Saxon site, with the initial work carried out by William Giffard and then predominantly by Henry of Blois. Although the site had curtain walls, towers and a moat, inside it was a luxurious palace, intended to demonstrate the huge wealth and power of the bishop.

Wolvesey continued in use until the 16th century, being updated by William of Wykeham and Cardinal Beaufort. Royal visitors often used the castle, particularly after Winchester Castle was damaged by fire in 1302. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries, however, the wealth of the bishops faded and the castle fell into disuse. A new mansion was built on the site in the 1680s and the old medieval buildings were left as ruins.

The ruins were restored in the 1920s by the Church Commissioners and the site was taken into the guardianship of the Ministry of Works in 1962. Today, the remains of the castle are managed by English Heritage and open to visitors.

History

11th-12th centuries

Wolvesey Castle was built in stages by several bishops of Winchester. By the time of the Norman invasion in 1066, Winchester was the administrative center of the kingdom, holding the royal treasury and the governmental records, and protected by city walls. It surrendered to William the Conqueror in November 1066, when the south-west salient of the walls was confiscated by the Crown and used to construct Winchester Castle.

The diocese of Winchester was immensely rich, holding lands across much of southern England. During the Anglo-Saxon period, the bishops had constructed a residence in the south-east corner of Winchester, close to the cathedral and St Mary’s monastery. William Giffard, a former Lord Chancellor, became Bishop of Winchester in 1100. He rebuilt the older palace around 1110, reusing parts of it and constructing a large hall – today known as the West Hall – for himself and his household.

Henry of Blois became bishop in 1129. Henry was one of the sons of the Count of Blois, a grandson of William the Conqueror, and a powerful political actor. King Stephen, who came to power in 1137, was his elder brother. Henry was already the Abbot of the tremendously wealthy Glastonbury Abbey, and now enjoyed the revenues of the diocese as well. Over the coming decades, he would turn Wolvesey Castle into a grand, fortified palace, alongside the various other castles and residences he developed across his estates.

Henry first extended the existing hall with an elaborate porchway and then, between 1137 and 1139, build a second large hall opposite the first. During the civil war known as the Anarchy, Henry fortified the site with protective walls and two towers. The castle survived the war intact, despite much of Winchester being destroyed by the forces of Henry I.

Forced into exile in 1154 when Henry I inherited the throne, Henry of Blois returned in 1158 and added a large gatehouse at Wolvesey, giving the castle its final form. Wolvesey would have been a symbol of Henry’s power and status, a secure administrative centre that could hold his household and visitors in lavish style.

13th-15th centuries

Richard of Ilchester probably carried on some of Henry’s work at the end of the 12th century. During the First Barons’ War, the bishop Peter des Roches supported King John against the rebel barons. When the barons, supported by the French, attacked Winchester in 1216, Roches’ illegitimate son, Oliver, held Wolvesey, which ultimately fell to French attack. After the war, Roches redeveloped the east hall.

Winchester Castle, as a royal fortification, had traditionally been used by the kings of England when they visited Winchester. In 1302, however, during a visit by Edward I, it caught fire. The damage was never fully repaired, and subsequently royal visitors to the city typically used Wolvesey instead. The resulting hospitality took place on a huge scale; one feat for Richard II in 1393 had 367 guests, for example, while the wedding feast of Henry IV in 1403 cost £522. 1It is difficult to accurately compare medieval financial figures with modern equivalents. See our article on medieval money for more details.

Between 1372 and 1376, Bishop William of Wykeham extended the castle slightly on the eastern side and upgraded the accommodation, including his own chambers. He also improved the defences in 1377, fearing a French invasion, and helped to repair the city defences.

16th-18th centuries

Cardinal Beaufort, his successor, modernised the castle in the first half of the next century, including building a new chapel. By the 16th century, however, the bishops were using Wolvesey less and less, although when the antiquarian John Leland visited in the 1530s, he could still describe the castle as “well tourrid [turreted], and the most part watered [moated] about”.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries and religious reforms undermined the wealth and power of many churchmen, and in 1551 the Winchester diocese estates were seized and broken up, although Wolvesey remained in the control of the bishops. The last major political event at the castle was the wedding banquet of Philip II of Spain and Mary Tudor in 1554.

During the civil war of the 1640s, Winchester was fought over by both sides, although Wolvesey was unused. During the interregnum, episcopal property was abolished, until the Restoration of King Charles II to power in 1660. Bishops Brian Duppa and George Morley then repaired Wolvesey, including reusing material from their former palace at Bishop’s Waltham. Morley wanted to rebuild the authority of the bishop, and a suitable residence at Wolvesey was important.

Morley changed his plans in the 1680s and instead built a new palace in a Baroque style on the Wolvesey site, dismantling many of the medieval buildings for materials. The work was completed under Sir Jonathan Trewlawny at the start of the 18th century. Subsequent bishops preferred to use Farnham Castle, and in 1785 Brownlow North pulled down most of the new palace, leaving only the west wing and the chapel.

19th-21st centuries

In 1840, Wolvesey became a Training School for the diocese, holding 50 students. It proved an unhealthy site, however, and after a major outbreak of sickness in 1858 it was decided to move the school to a new location in the north of Winchester. The castle was then used as one of the master’s houses of Wykeham College.

The diocese of Winchester was broken into three parts in 1927, and Bishop Theodore Woods moved back into Wolvesey. Woods commissioned a restoration of the 17th century mansion and the wider side under the architect W. D. Caroe in 1928, including the renovation of the chapel. The resulting building is now called Bishop’s House, and is still used by the bishops of Winchester

After the Second World War, the Church Commissioners who now controlled the estate were unwilling to maintain Wolvesey, and they asked the Ministry of Works to take it into guardianship. The Ministry was cautious, as it regarded the interwar restoration work to have been badly undertaken and a potential embarrassment to them. Nine years later, in 1962, it was finally taken into guardianship.

The castle was excavated as part of a major Winchester archaeological project between 1961 to 1971, under direction of Martin Biddle. The programme of work determined the main sequence of construction, particularly in the early parts of the 12th century. In the 21st century, the castle is protected under UK law as a scheduled monument as a Grade I listed building. It is maintained by English Heritage, the successor to the Ministry of Works, and is open to visitors.

Architecture

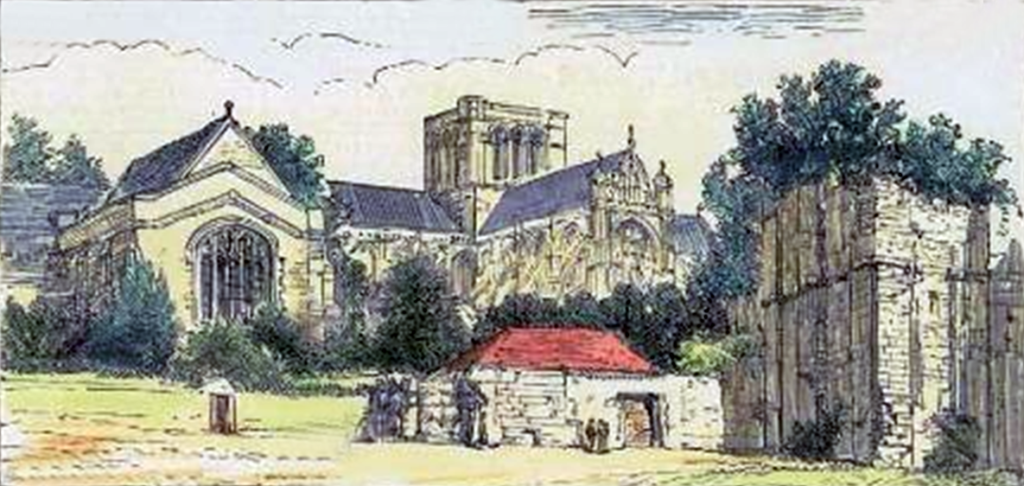

Wolvesey Castle lies in the south-east corner of Winchester, and was bounded by the city walls to the south and east. The site would have been tremendously impressive when first built; the historian Anthony Emery describes the ruins as “the largest secular survival of the 12th century”, while English Heritage considers the castle to be “one of the greatest medieval buildings in England”.

Categorising Wolvesey is challenging. When first built, as the historian John Wareham notes, it was intended to be a palace rather than a castle. The fortifications added in the course of the 12th century changed its character, making it much more secure, although still not primarily a military fortification – Norman Pounds describes the result as “a lightly defended castle… a palace clustered around a tower keep”.

The castle comprised two wards, the inner ward familiar to visitors today, and an outer ward to the south. The castle would have been approached in medieval times from the north through the main city, although today visitors access it from the south side. There was a later entrance through the city walls to the south, probably used primarily for service and commercial traffic.

The inner ward measures approximately 100 m by 90 m across (328 ft by 295 ft). It was was surrounded by a wide moat, but this was filled in during the redevelopment of the site in the 1700s. The buildings were constructed from flint rubble and ashlar blocks, which were then rendered and whitewashed: today, only the flint core typically survives. W. D. Caroe’s restoration work can be seen across the site, typically marked by the red tiles he added to conserve the fabric of the buildings. The buildings were fed by a complex sequence of water pipes and tanks, a considerable innovation for the period.

The gatehouse, known as Woodman’s Gate, was built to protect the north side of the castle soon after 1158. It originally had a drawbridge across the moat and arrow-loops to cover the approaches. William of Wykeham redeveloped the gatehouse in the 14th century to accommodate his treasurer and the exchequer, producing a more luxurious set of chambers.

The West Hall was built around 1100. It formed a large set of chambers for the household, with a three-storey tall tower at the south end, that originally held the bishop’s exchequer. A chapel was attached to the tower, while the west side of the hall held a raised garden. An elaborate porch entrance and a latrine block were later added on the north side.

The East Hall was constructed around 1139 and faced the earlier block. It contained another set of chambers and was used for ceremonies and public engagements. It was redesigned in 1441 by Cardinal Beaufort, when a new roof and windows were added. The hall was linked to a set of defences, including Wymond’s Tower, a heavily reinforced latrine tower, and the Keep, a large kitchen block with defensive features.

The outer ward contained service buildings for the castle, including stables and barns. It also held the bishop’s prison and the wool house, which controlled the trade in wool from the episcopal estates.

Visiting the castle

Bibliography

- Benham, William. (1884) Winchester. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge: London, UK.

- Biddle, Martin. (1964) “Excavations at Winchester, 1962-63 : Second interim Report” Antiquaries Journal Volume 44.

- Biddle, Martin. (1965) “Excavations at Winchester, 1964: Third interim Report” Antiquaries Journal Volume 45.

- Biddle, Martin. (1966) “Excavations at Winchester 1965; Fourth interim report” Antiquaries Journal Volume 46.

- Biddle, Martin. (1967) “Excavations at Winchester, 1966; Fifth interim report” Antiquaries Journal Volume 47.

- Biddle, Martin. (1968) “Excavations at Winchester 1967: Sixth interim report” Antiquaries Journal Volume 48.

- Biddle, Martin. (1969) “Excavations at Winchester 1967: Seventh interim report” Antiquaries Journal Volume 49.

- Biddle, Martin. (1972) “Excavations at Winchester, 1970: Ninth interim Report” Antiquaries Journal Volume 52.

- Biddle, Martin and Beatrice Clayre. (2000) Winchester Castle, the Great Hall and Round Table. Hampshire County Council: Winchester, UK.

- Biddle, Martin, Sally Badham and A.. C. Barefoot. (2000). King Arthur’s Round Table: An Archaeological Investigation. Boydell Press: Woodbridge, UK.

- Cunliffe, Barry. (1962) “The Winchester City Wall,” Hampshire Field Club Proceedings, Volume 22.

- Emery, Anthony. (2006) Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales: Volume 3 Southern England. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

- Kynan-Wilson, William. (2021) Henry of Blois: New Interpretations. Boydell and Brewer: Woodbridge, UK.

- Parliament. Parliamentary Papers, Volume 21, Part 1. (1859) House of Commons, London, UK

- Vincent, Nicholas. (2002) Peter des Roches: An Alien in English Politics, 1205-1238. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK.

- Wareham, John. (2000) Three Palaces of the Bishops of Winchester: Wolvesey (Old Bishop’s Palace), Hampshire; Bishop’s Waltham Palace, Hampshire; Farnham Castle Keep, Surrey. English Heritage: London, UK

Attribution

The text of this page is licensed under under CC BY-NC 2.0. Photographs on this page include those from the Flickr and British Museum websites, and are attributed as follows: “Ruins of the castle in the 19th century“, photograph copyright the Trustees of the British Museum, released under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0; “Panorama“, author Stu Smith, released under CC BY-ND 2.0.