Sandsfoot saw service during the English Civil War, when it was held by Parliament and Royalists in turn during the conflict. It survived the interregnum but, following Charles II’s restoration to the throne, the fortress was withdrawn from military use in 1665.

By the early 18th century, Sandsfoot was in ruins, its stonework taken for use in local building projects. The clay cliffs on which the castle had been built had always been unstable and subject to erosion. The castle’s gun platform began to collapse into the sea and, by the 1950s, had been entirely destroyed. The ruins were closed to visitors on safety grounds, although civic gardens were planted alongside it in 1951. Repairs were undertaken between 2009 and 2012 at a total cost of £217,800, enabling the site to be reopened to the public. Historic England considers Sandsfoot to be “one of the most substantial examples” of the 16th-century blockhouses to survive in England.

History

16th century

Sandsfoot Castle was built as a consequence of international tensions between England, France and the Holy Roman Empire in the final years of the reign of King Henry VIII. Traditionally the Crown had left coastal defences to the local lords and communities, only taking a modest role in building and maintaining fortifications, and while France and the Empire remained in conflict with one another, maritime raids were common but an actual invasion of England seemed unlikely. Modest defences, based around simple blockhouses and towers, existed in the south-west and along the Sussex coast, with a few more impressive works in the north of England, but in general the fortifications were very limited in scale.

After 1533, Henry broke with popes Pope Clement VII and Paul III in order to annul the long-standing marriage to his wife, Catherine of Aragon, and remarry. Catherine was the aunt of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, and Charles took the annulment as a personal insult. This resulted in France and the Empire declaring an alliance against Henry in 1538, and the Pope encouraging the two countries to attack England. An invasion of England appeared certain. In response, Henry issued an order, called a “device”, in 1539, giving instructions for the “defence of the realm in time of invasion” and the construction of forts along the English coastline.

Sandsfoot Castle was built to protect the Weymouth Bay anchorage, being placed on cliffs overlooking the waterway, opposite Portland Castle on the other side. Sandsfoot was a blockhouse, intended to defeat enemy ships using a battery of heavy artillery, and had minimal protection against an attack from the land. It was completed by 1541, run by a captain appointed by the Crown, and cost £3,887 to build.1Comparing early modern costs and prices with those of the modern period is challenging. £3,887 in 1541 could be equivalent to between £1.9 million and £920 million in 2014, depending on the price comparison used. £383 in 1583 could equate to between £92,000 and £34 million; £211 in 1611 to between £30,000 and £11 million; £459 in 1623 to between £76,000 and £23 million. For comparison, the total royal expenditure on all the Device Forts across England between 1539–47 came to £376,500, with St Mawes and Sandgate Castle, for example, costing £5,018 and £5,584 apiece.

There was probably an early agreement that the nearby village of Wyke Regis had a responsibility to support the castle, and in exchange they came to traditionally enjoy an exemption from taxes and militia duties. The antiquarian John Leland visited the castle soon after its construction, describing it as “a right goodlie and warlyke castle” with “one open barbican”, probably referring to the castle’s gun platform.

Coastal erosion quickly began to threaten the castle, causing what was reported as a “great gulf” on its seaward side, and repairs costing £383 were necessary by 1583,2Comparing early modern costs and prices with those of the modern period is challenging. £3,887 in 1541 could be equivalent to between £1.9 million and £920 million in 2014, depending on the price comparison used. £383 in 1583 could equate to between £92,000 and £34 million; £211 in 1611 to between £30,000 and £11 million; £459 in 1623 to between £76,000 and £23 million. For comparison, the total royal expenditure on all the Device Forts across England between 1539–47 came to £376,500, with St Mawes and Sandgate Castle, for example, costing £5,018 and £5,584 apiece. completed by John Wadham of Catherston, MP and Recorder for Weymouth and “Captain of the Queen’s Majestie at Sandesfoot Castle” who died in 1584. During the invasion scare that accompanied the Spanish Armada of 1588, the normal garrison of Sandsfoot was supplemented by another 50 men.

17th–19th centuries

Repairs were made to the castle between 1610 and 1611 by the captain, Sir George Bampfield, at a cost of £211.3Comparing early modern costs and prices with those of the modern period is challenging. £3,887 in 1541 could be equivalent to between £1.9 million and £920 million in 2014, depending on the price comparison used. £383 in 1583 could equate to between £92,000 and £34 million; £211 in 1611 to between £30,000 and £11 million; £459 in 1623 to between £76,000 and £23 million. For comparison, the total royal expenditure on all the Device Forts across England between 1539–47 came to £376,500, with St Mawes and Sandgate Castle, for example, costing £5,018 and £5,584 apiece. A survey in 1623 carried out by Sir Richard Morryson showed the castle to be equipped with ten iron guns – one culverin, five demi-culverins, two sakers, a minion and a falcon – and garrisoned by its captain, five gunners and three soldiers. It was in a poor condition, and one corner of the gun platform had been undermined by the sea; Morryson’s team estimated the likely costs of repairs to amount to £459.

During the English Civil War between the supporters of Charles I and Parliament, Weymouth was predominantly Parliamentarian in loyalty and the surrounding forts were held by their garrisons. Robert Dormer, the Earl of Carnarvon, entered Dorset with an army in 1643 and Weymouth surrendered, resulting in Sandsfoot Castle being controlled by the Royalists between August 1643 and June 1644. During this period the castle may have been used as a Royalist mint.4The historian Henry Symonds presented an argument for the use of Sandsfoot as a mint on the basis of the labelling of coins from this period with an “SA”, and their similarity to other coins struck at Weymouth during the Royalist control of the town. If the coins concerned were not struck at Sandsfoot, they were likely the product of the Salisbury mint. Symond argues that the mint’s equipment may have been evacuated to Portland Castle when the Royalists left. Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex, then retook the county for Parliament; Colonel William Ashburnham, the Royalist governor of Weymouth, retreated to Portland Castle without a fight. Devereux approached Sandsfoot and, after three hours of negotiations, the fort surrendered to him. In 1647, Parliament ordered the garrison at the castle to be demobilised but this did not occur, and John Hayne was appointed as its new captain.

Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660 and the next year a fresh order was given to demobilise the garrison at Sandsfoot. An argument then broke out between Humphrey Weld, the lieutenant-governor of Portland and captain of Sandsfoot Castle, and Charles Stewart, the Duke of Richmond, over the control of the local defences. The village of Wyke Regis petitioned Weld in a bid to prevent the demobilisation, concerned that their traditional exemptions from militia service would be revoked by the Duke. Weld championed their case but was dismissed from his post as lieutenant-governor, and the Duke occupied Sandsfoot with his militia. Weld appealed to the government and in 1665 a compromise was announced in which Weld would be reappointed to his role as lieutenant-governor, while Sandsfoot would be declared redundant and be demolished. The order for its destruction was never carried out, and the castle was used as a storehouse until at least 1691.

By 1725, the castle had become ruinous. Early in the century, the remains of the castle was sold to the town of Weymouth, whose people reused some of the stone to construct their new town bridge. Local tradition in the 19th century maintained that several houses in Weymouth were also constructed using stone taken from the castle. In 1825, the carved stone Elizabethan arms of the castle were moved to All Saints Church in Wyke Regis. Captains continued to be formally appointed, however, and Gabriel Stewart held the post as late as 1795.

The majority of the gun platform collapsed into the sea as the cliffs eroded. It is uncertain precisely when this occurred; in a prolonged historical debate over this during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the historian Henry Symonds argued that the first falls occurred during the 18th century, W. Norman placed the main fall in 1835, and T. Groves argued in favour of a more recent collapse in the second half of the 19th century. The ruined castle was drawn and painted by various artists in the 18th and 19th centuries, including Samuel Buck, J. H. Grimm, C. Sawyer and Edward Pritchard. The castle featured in Joseph Drew’s short novel “the Poisoned Cup” in 1876.

20th–21st centuries

In 1902, the Weymouth Corporation purchased the castle for the town from the Department of Woods and Forests for a total of £150.5Equivalent modern prices of early 20th century monetary sums depend on the index used to make the comparison. £150 in 1902 could equate to between £14,800 in 2014, if valued using the a GDP Deflator, or up to £142,000, if valued using a share of GDP. During the Second World War the castle probably housed an anti-aircraft battery as part of the defences created around Portland Harbour. Despite the construction of the Portland breakwaters nearby, the unstable clay cliffs remained vulnerable to erosion; in 1930 the ruins were closed to the public due to safety concerns and the remaining embrasure of the gun platform collapsed during in the 1950s.

In 2009, £23,100 was awarded by the Heritage Lottery Fund for an initial survey of the site, which by now had been placed on English Heritage’s register of listed buildings at risk of decline, followed by a further £194,700 in 2011 for substantial repair work. As part of the work, a three-dimensional laser scan of the stonework was undertaken, and a steel and oak walkway was installed around the interior of the castle. The castle reopened to the public in 2012, and the following year it was removed from English Heritage’s at risk register. The castle is protected under UK law as a grade II* listed building and as a scheduled ancient monument.

Architecture

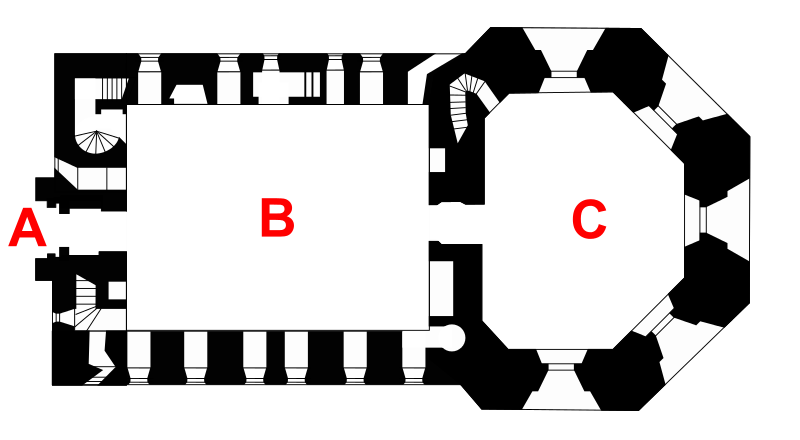

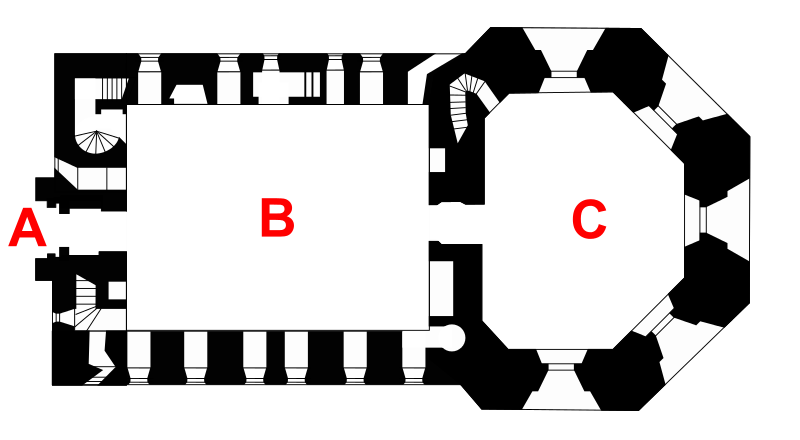

Sandsfoot Castle was built from Portland stone with ashlar facings and a rubble core. It comprised a main blockhouse attached to an octagonal gun room, overlooking the sea. The two-storey blockhouse is 42 by 32 feet (12.8 by 9.8 m) across, with a gate-tower on its landward side. It probably originally had four rooms for the accommodation and cooking facilities for the garrison, with staircases leading up to the first floor and down into its basement. The gate-tower held a small room on the first floor and was designed to hold a portcullis. The one-storey gun room was approximately 36 by 28 feet (11.0 by 8.5 m) across with five embrasures for guns and a flat roof that also probably supported artillery. Both the gun room and the main block were probably protected by parapets.

The gun room has been lost to erosion, although the south-western embrasure is still visible where it fell onto the beach below. The ashlar facings of the blockhouse have been largely robbed, although some elements remain, and the roof and floors have been lost. Historic England considers that the castle “represents one of the most substantial examples” of an unaltered 16th-century blockhouse in England.

The castle originally had an outer ward, reached over a bridge, and stables, although these have been both been lost. Protective rectangular earthworks were constructed to protect the castle on the landward side, probably in 1623, with two bastions in the north and west corners, and some form of stone structure along the earthworks. In the 18th century these earthworks were described as forming a “deep trench” and mid-19th century accounts suggested that they were around 12 feet (3.7 m) deep. Now only 100 feet (30 m) of the bank and ditch survives, with the earthworks approximately 10 metres (33 ft) wide overall and 2.2 metres (7 ft 3 in) deep between the top of the bank and the base of the ditch. The north bastion still survives largely intact, although the west has been mostly destroyed. Outside the entrance to the earthworks are the Sandsfoot Gardens, civic gardens dating from 1951, designed in a Tudor style with an ornamental pond.

Visiting the castle

Bibliography

- Anonymous (n.d.). A Guide Book to Weymouth and Melcombe Regis, with the Adjacent Villages and the Island of Portland. Weymouth, UK: A. A. Adey. OCLC 504005832.

- Anonymous (1785). The Weymouth Guide: Exhibiting the Ancient and Present State of Weymouth and Melcombe Regis. Weymouth, UK: n.p. OCLC 316773470.

- Barber, David; Mills, Jon; Andrews, David (2011). 3D Laser Scanning for Heritage: Advice and Guidance to Users on Laser Scanning in Archaeology and Architecture (2nd ed.). Swindon, UK: English Heritage.

- Barrett, W. Bowles (1910). “Weymouth and Melcombe Regis in the Time of the Great Civil War”. Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club. 31: 204–229.

- Bellamy, Peter; Pinder, Claire; Le Pard, Gordon (2011). Weymouth: Historic Urban Characterisation. Dorchester, UK: Dorset County Council and English Heritage.

- Biddle, Martin; Hiller, Jonathon; Scott, Ian; Streeten, Anthony (2001). Henry VIII’s Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books. ISBN 0904220230.

- Ellis, George Alfred (1829). The History and Antiquities of the Borough and Town of Weymouth and Melcombe. London, UK: Baldwin and Craddock. OCLC 225033766.

- Groves, T. B. (1879). “Notes on Sandsfoot Castle”. Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club. 3: 20–24.

- Hale, John R. (1983). Renaissance War Studies. London, UK: Hambledon Press. ISBN 0907628176.

- Harrington, Peter (2007). The Castles of Henry VIII. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781472803801.

- King, D. J. Cathcart (1991). The Castle in England and Wales: An Interpretative History. London, UK: Routledge Press. ISBN 9780415003506.

- Morley, B. M. (1976). Henry VIII and the Development of Coastal Defence. London, UK: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. ISBN 0116707771.

- Norman, W. C. (1920). “Sandsfoot Castle, Weymouth”. Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club. 41: 34–38.

- Norrey, P. J. (1988). “The Restoration Regime in Action: The Relationship between Central and Local Government in Dorset, Somerset and Wiltshire, 1660–1678”. The Historical Journal. 31 (4): 789–812.

- Saunders, Andrew (1989). Fortress Britain: Artillery Fortifications in the British Isles and Ireland. Liphook, UK: Beaufort. ISBN 1855120003.

- Symonds, Henry (1913). “Are the Coins of Charles I Bearing the Letters “SA” Correctly Assigned to a Mint at Salisbury?”. The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society. 13: 119–122.

- Symonds, Henry (1914). “Sandsfoot and Portland Castles”. Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club. 35: 27–40.

- Thompson, M. W. (1987). The Decline of the Castle. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1854226088.

- Walton, Steven A. (2010). “State Building Through Building for the State: Foreign and Domestic Expertise in Tudor Fortification”. Osiris. 25 (1): 66–84.

Attribution

The text of this page was adapted from “Sandsfoot Castle” on the English language website Wikipedia, as the version dated 26 September 2018, and accordingly the text of this page is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Principal editors have included Hchc2009, Ajsmith141 and CottrellS, and the contributions of all editors can be found on the history tab of the Wikipedia article.

Photographs on this page are drawn from the Wikimedia website, as of 26 September 2018, and attributed and licensed as follows: “Sandsfoot Castle“, author Bob Ford, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Sandsfoot Castle“, author Maurice D. Budden, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Sandsfoot Castle, 1756” (Public Domain); “Sandsfoot Castle, 1825” (Public Domain); “Sandsfoot Castle Gardens, Weymouth, Dorset“, author Mike Smith, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Sandsfoot Castle plan – labelled“, author Hchc2009, released under CC BY-SA 4.0.