Dudley Castle is a ruined medieval fortification in the West Midlands. It was constructed after the Norman conquest of England, probably by either Ansculf de Picquigny or his son, William Fitz Ansculf. The early castle was a substantial motte and bailey earthwork design with an inner and outer ward, located on the hill overlooking the local settlement of Dudley. After the revolt against Henry II in 1173, the King ordered that the castle be pulled down.

The de Somery family began to rebuild the castle in the 13th century, and John de Somery built a great tower on the motte, helping to create a well-fortified but comfortable country home. Sir John Dudley took possession of the castle in 1535 and rebuilt much of the interior, employing Sir William Sharrington to design a new range of Elizabethan buildings along the north-east side of the inner ward.

The castle was used as a base for Royalist forces during the English Civil War of 1642-1646, until it was taken by Parliamentary soldiers after a three week siege in April 1646. Parliament ordered that the fortification be slighted, damaged to as to put it beyond military use, and much of the curtain wall and the great tower was pulled down. With the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, the castle was reoccupied and put into good repair.

In 1750, however, it caught fire and was gutted by the blaze. Remaining in ruins, the castle and the surrounding grounds became used for recreation in the 19th century; in 1937 they became part of the new Dudley Zoo, and remain open to visitors as part of this attraction.

History

11th-12th centuries

Dudley Castle was built following the Norman conquest of England by either Ansculf de Picquigny or his son, William Fitz Ansculf, who had formed part of King William’s invasion force. Before the conquest, Dudley had been an Anglo-Saxon manor, held by Earl Eadwine. Following the Anglo-Saxon revolts of 1070, however, the King granted Ansculf extensive lands stretching across middle England. These estates were eventually known as the Honour of Dudley, and the castle formed its administrative centre, or caput.

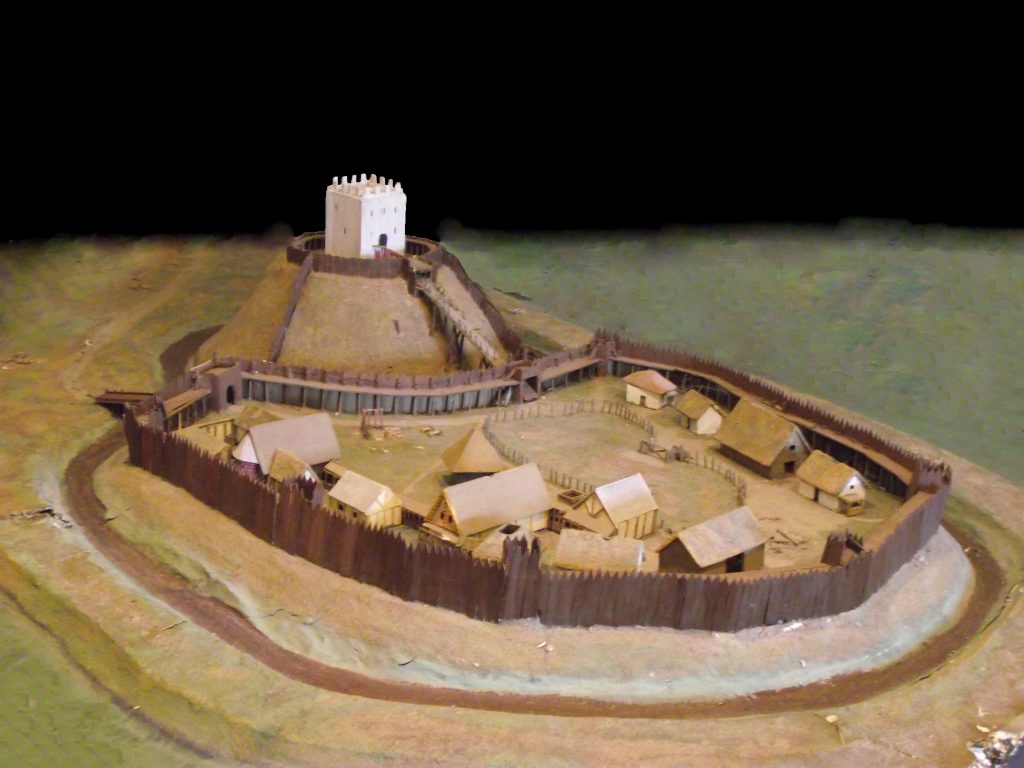

It is unknown exactly when Dudley Castle was erected. The first record of it is in the Domesday Book of 1086, by when it was owned by William Fitz Ansculf; given the sequence of events, the castle may well have been built soon after 1071. The castle was a large motte-and-bailey design, with timber defences on top of the earthworks, and an outer ward lying beyond a defensive ditch. The keep on the centre of the motte would have probably been very large.

The lands around the fortification formed was what known as a castelry, or castle-guard system: local estates were granted to knights in return for their service in protecting the local castle. At some point, a deer park, later called the “Old Park”, was established beside the castle.

Fulke Paganel acquired much of the Honour by marriage, and then probably began to rebuild the timber defences of the castle in stone during the early 12th century. Fulke’s son, Ralph, inherited the castle and estates, and in turn his own son, Gervase, succeeded to the lands.

After 1135, civil war broke out in England between the rival supporters of the Empress Matilda and King Stephen. Gervase supported the Empress: in response, Stephen attacked Gervase at Dudley Castle in 1138. Stephen does not seem to have been able to seize the castle, but looted and devastated the surrounding area.

The civil war came to an end in 1153, with Matilda’s son, Henry II, assuming the throne. Gervase established a priory just west of the castle in 1161; religious establishments such as this were often linked to castles, and an important part of showing lordship over a region. In 1173, however, Gervase supported Henry the Young King in his rebellion against Henry II, his father. Henry II won and ordered that Dudley Castle be pulled down as a punishment for Gervase’s role in the revolt. How much was actually destroyed is uncertain.

Gervase managed to restore himself to the King’s favour by 1176, partially by paying the Crown 500 marks,1It is difficult to accurately compare early modern financial figures with modern equivalents. See our article on medieval money for more details. and regained control of his lands and Dudley Castle. Gervase’s nephew, Ralph de Somery, inherited the Honour when Gervase died in 1194.

13th – 14th centuries

Ralph de Somery and his descendents owned Dudley Castle for the next century. Roger de Somery, Ralph’s brother, ultimately inherited the castle, but he caused offence to Henry III by failing to attend court, and Dudley Castle was temporarily seized by the Crown in 1229. Roger established a second deer park for hunting, later called the “New Park”, in 1247 near the castle and the town.

Roger began to rebuild the castle, but he did not possess the necessary royal permission. As a result, Henry ordered him to cease work in 1262. With conflict with the barons brewing, however, Henry changed his mind and in 1264 granted him a licence to crenellate the property. Work may not have advanced very far before Roger’s death in 1272, although the castle seems to have been largely complete by the time that Roger’s son – another Roger – died in 1291.

John de Somery then inherited the castle and appears to have continued to expand the castle. John was probably responsible for building the great tower after 1308, to mark his new status as Lord Somery. He was widely disliked across the region for abusing his power and authority to extort money and manpower, however, and there were complaints in 1311 that he had been using forced labour to carry out construction work at Dudley. The new castle was still militarily secure, but had much better service facilities and living accommodation than the earlier Norman design, as befitted a property intended to house an extremely wealthy family.

Meanwhile, the village of Dudley had begun to develop into a town. By the late 13th century, there was a local coal mine and two iron-working smithies, supporting a growing settlement with its own markets.

John Sutton inherited the castle through his wife on de Somery’s death in 1321. During the later years of Edward II’s reign, the Despenser family took effective power over much of England and Wales. John was imprisoned by the Despensers until he agreed to hand over a range of properties, including Dudley Castle to Hugh Despenser the Younger in 1326. The Despensers were deposed and executed the following year, and Sutton went on to extend the buildings at Dudley, probably building the hall and the chapel.

15th-17th centuries

The Sutton family continued to prosper and were ennobled in 1423. In due course, John Lord Dudley inherited Dudley Castle in 1532 but proved a poor business manager. He ran up huge debts and mortgaged the family lands to Sir John Dudley, later to become the Duke of Northumberland. He soon found himself unable to pay the interest on the loan and in 1535 had to sell the castle to Sir John.

Sir John Dudley employed the architect Sir William Sharrington to build a new, luxurious range of buildings, in a contemporary Italian Renaissance style, along the eastern side of the castle, overlooking the neighbouring countryside. He also acquired the local priory in 1540 during the Reformation of the Monasteries. Sir John fell from power in 1554, and Queen Mary returned the castle to John Lord Dudley’s son, Edward Dudley.

The town of Dudley itself fell into poverty, and by 1585 was described by a visitor as “one of the poorest townes that I have sene in my life”. The castle was considered as a prison for holding Mary Queen of Scots the same year. The government report noted that the accommodation in the castle was more limited than would have been liked – the lodgings lacked inner chambers, which by now were fashionable – and was generally poorly equipped. There was plenty of coal and wood in the surrounding town, but this had to be purchased, rather than coming directly from a castle estate. Given the amount of work required to make use of Dudley Castle, the Crown decided not to place the Queen there.

In 1642, civil war broke out between the royalist supporters of Charles I and those of Parliament. In August, Dudley Castle was seized by Colonel Thomas Leveson, who was joined by local gentlemen and industrial labourers. Frances Sutton, who had married Humble Ward, the Baron Ward in 1643, continued to live in the castle but took no part in the wider conflict. The ironworks around the castle were put to use to produce war materiel, while Leveson and his men raided the countryside to collect money to pay the wages of the soldiers.

From Dudley and other strongholds along the region, the Royalists were able to control the West Midlands, and Leveson mounted several attacks in and around Birmingham, which was held by Parliament. The Earl of Denbigh responded by besieging Dudley Castle in June 1644 for three weeks, until a Royalist army relieved the position.

The war steadily turned against the Royalists and, by April 1646, Parliament was able to send a new army to attack Dudley, under the command of Sir William Brereton. Their forces took the town and the priory and began to fortify their positions. Leveson mounted an immediate counterattack, but was pushed back into the castle.

Negotiations for a surrender quickly began, with Leveson holding off for instructions from King Charles in Oxford. When none arrived, he eventually surrendered the castle on good terms on 13 May, handing over considerable supplies to the Parliamentary forces. Despite the assurances prior to the surrender, Leveson was ultimately forced into exile by Parliament.

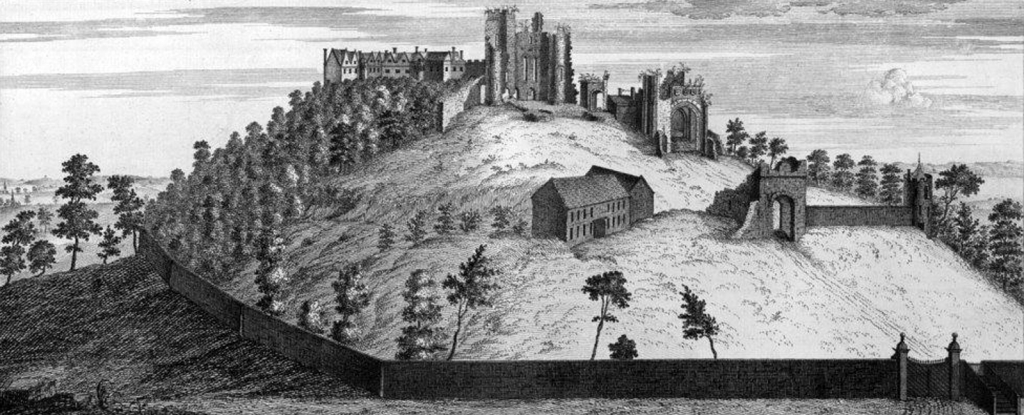

Brereton put Captain Robert Tuthill in charge of the new garrison, advising that the castle be kept as a Parliamentary base. London, however, soon sequestered the Dudley lands and in 1647 gave orders that the castle slighted, or deliberately destroyed, so as to make the castle impossible to defend militarily. The southern part of the great tower, parts of the curtain wall and the barbican were demolished; the decision to demolish the parts of the tower overlooking the town would have deliberate, communicating a symbolic, as well as practical, message about the new authority of the Parliamentary government.

After the Restoration of King Charles II to the throne in 1660, Dudley Castle passed back to the Crown, before returning to Frances Sutton in 1667. It was placed under the control of trustees following Humble Ward’s death in 1670 and then rented out, before being reoccupied by the Ward family on an irregular basis for formal occasions. The castle was brought back into good repair, and contemporary accounts describe its hunting park as being well stocked with game. The lodgings alongside the gatehouse were built around this time.

18th – 21st centuries

Dudley began to prosper once again, but towards the middle of the 18th century the Wards appear to have to ceased to use Dudley Castle, preferring their property at Himley, and left it in the management of a small number of staff. On 14 July 1750, the castle caught fire, local tradition describing this as having been caused by a gang of coiners melting down bullion within the castle walls. In any case, the castle burnt for three days, the lead roof melting in the blaze, leaving it a ruined shell.

John Ward, the Baron Ward, did not repair the ruins. By now Dudley was an industrial town, based on the iron and coal trade, and cattle and trespassers passed easily into the castle through the broken Old Park walls. During the French Revolutionary Napoleonic Wars, John Ward, who would later inherit the barony, became the colonel of the local volunteer infantry and cavalry regiments. The castle was used for training and parades by the units.

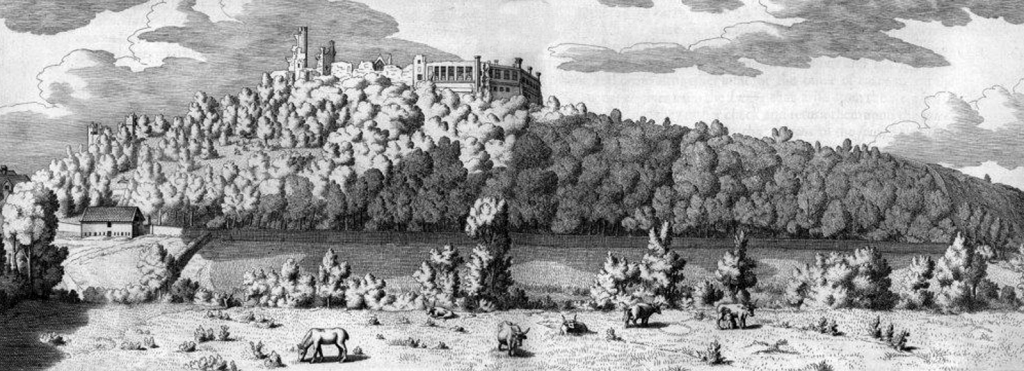

In 1818, William Ward, the Viscount Dudley and Ward, enlarged and repaired the park perimeter and cut new avenues through the trees. He had earlier carried out some reconstruction of the ruins, including re-crenellating the great tower and clearing away the debris from the slighting after the civil war, turning the site into a viewing platform.

William Ward, the Earl of Dudley, later opened the site up for local recreation in the middle of the 19th century. Two cannon from the Crimea War were brought to the castle for display as trophies, and a guide book for visitors was published in 1885. The centre of the castle was used for Whitsuntide fetes and similar occasions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

During the 1930s, the third Earl of Dudley, William Ward, decided to use the castle ruins as the basis for a public zoo. He hoped that the castle would form the central part of this new attraction. Together with Ernest Marsh, a local businessman, and Captain Frank Cooper, who owned Oxford Zoo, they established the new venture.

The Office of Works was concerned about the impact of the plans on the castle and its immediate environment and intervened. As a result, while part of the castle’s outer court was built over to provide additional space for the modernist-styled zoo, the height and layout of the buildings were curtailed. The development cost £250,000 to construct, and attracted nearly 700,000 visitors in its first summer of 1937. Archaeological excavations were carried out in the mid-1980s.

In the 21st century, the castle remains open to visitors, and is protected under UK law as a Scheduled Monument and a Grade I listed building.

Architecture

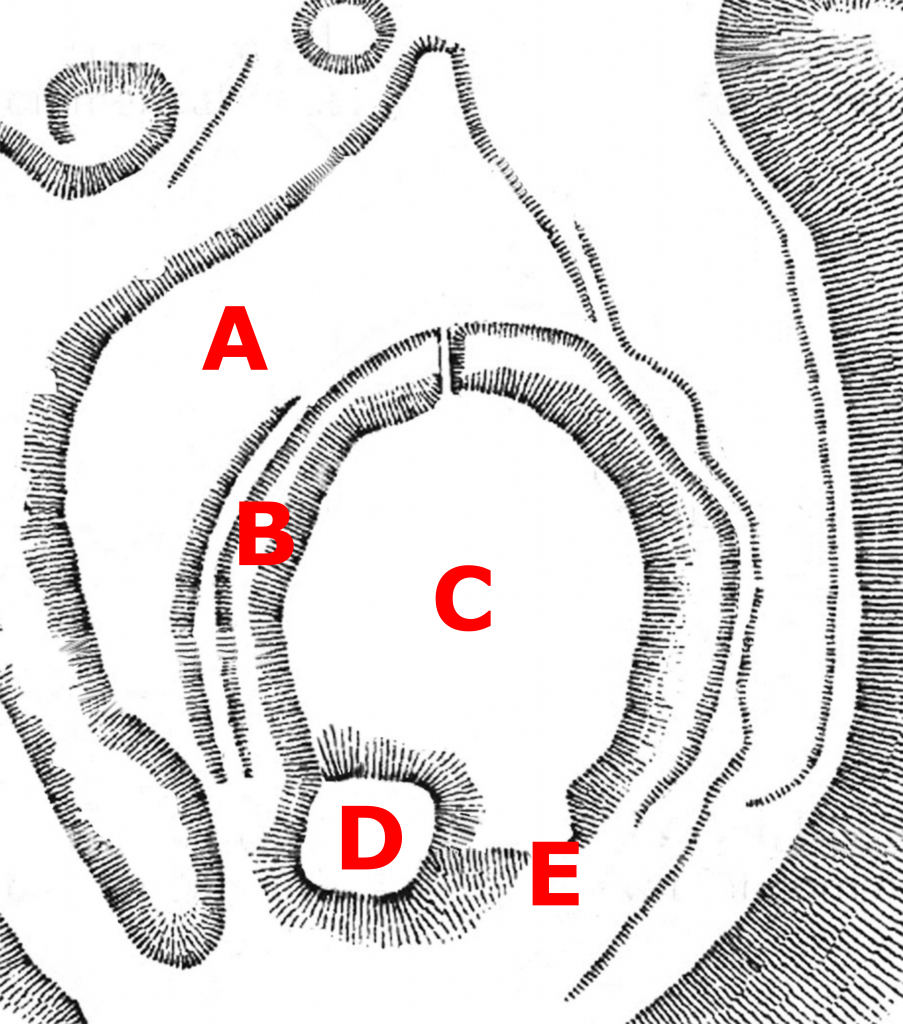

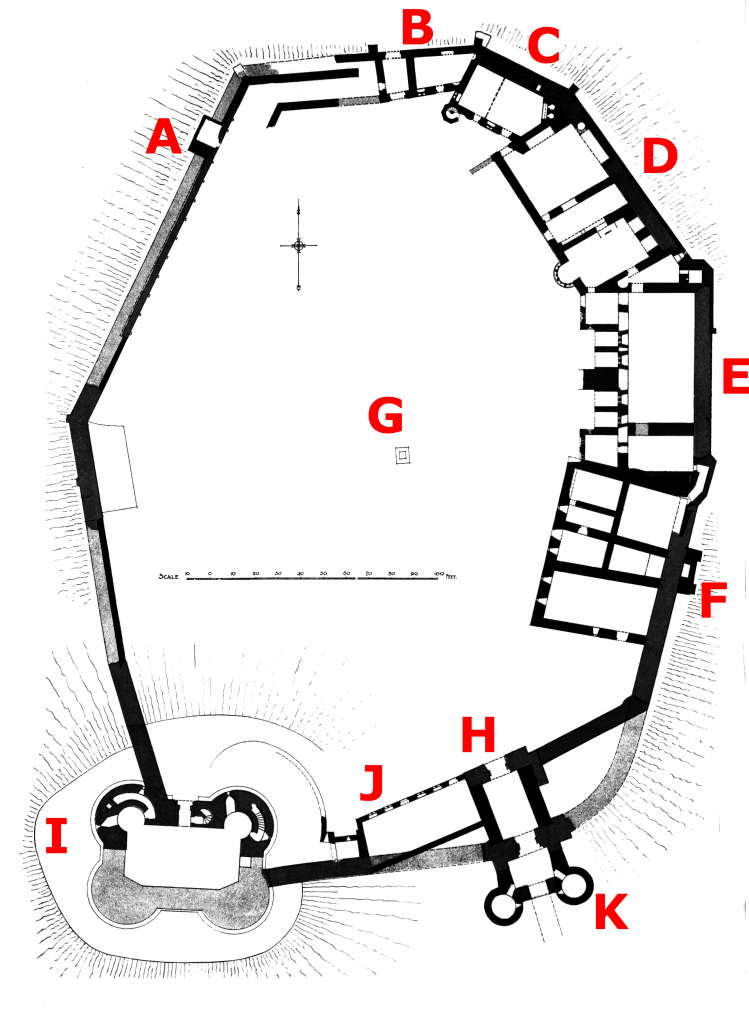

Dudley Castle is built on a limestone ridge overlooking the local town, possibly on the site of an older Iron Age fort. The surrounding landscape has been quarried over the centuries, and contains both natural and artificial caverns. The castle originally formed a motte, an inner ward, and a larger outer ward to the north and west.

The motte is positioned on the south-west side of the castle, overlooking the town. It is partially artificial, taking advantage of the natural stone outcrop, reinforced with with limestone rubble and clay. The first defensive structure on the motte was a large timber keep, constructed in the 11th century; this may have replaced in stone by the early 12th century.

The current great tower dates from the 14th century and is constructed from limestone rubble with sandstone dressings. Measuring 50 by 25 feet (15.2 by 7.6 m) across, it has four circular corner towers and originally had two storeys, with walls up to 11 feet 4 inches (3.45 m) thick in places. Its entrance way is vaulted, and would have been protected by a portcullis. The interior would have been subdivided to form comfortable living accommodation. Attempts were made to dig a well within the tower, but these seem to have been abandoned. Slighted in 1647, the great tower’s battlements date from reconstruction work in the early 19th century.

The inner ward forms an oval shape approximately 360 by 270 feet (110 by 82 m)

across, protected by a curtain wall approximately 8 feet (2.44 m) thick, except for the thinner sections rebuilt along the western side to repair the slighting of 1647.

The inner ward is entered through a gatehouse on the south-east side. This combines 12th and 14th century work, and was originally three storeys tall, made of limestone rubble and sandstone, with the vaulted passageway protected by doors and portcullises. The gatehouse was further protected by a 14th-century barbican and a drawbridge, although only the foundations of these now remain.

A set of two-storey tall lodgings, also known as “the stables”, were built onto its west side in the late-17th century. A further set of buildings were at one time built to the east, along the curtain wall between the chapel and the gateway, but were demolished when this section of wall was slighted.

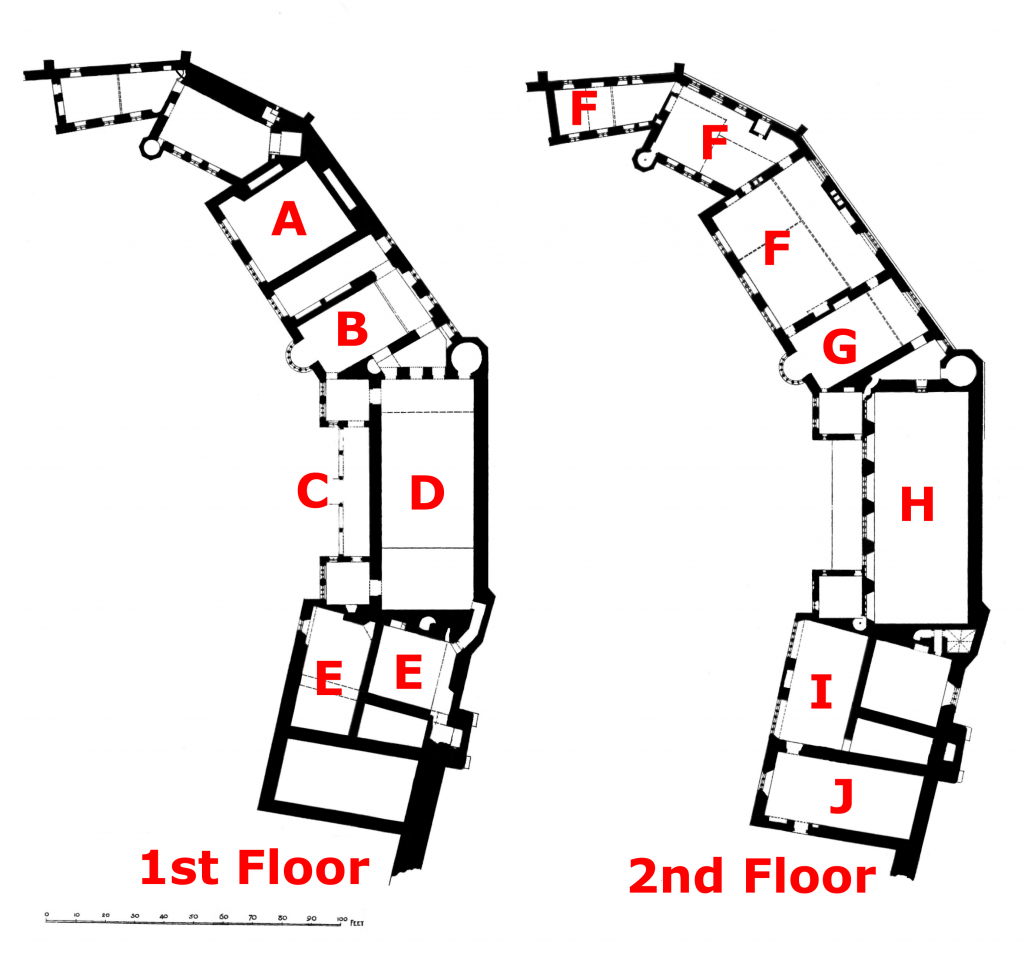

Along the eastern side of the inner ward are the 16th-century domestic quarters built from limestone rubble and sandstone, probably incorporating earlier medieval structures. These comprise a central hall, flanked by two ranges, attached to a further set of service buildings along the north side of the ward. Destroyed by fire in the 18th century, they remain ruined.

The central hall is entered up a flight of steps and through a loggia with a Corinthian arcade, fashionable at the time. The hall was two storeys tall and 78 by 31 feet (23.8 by 9.4 m) across, with a dais on the southern end. It was probably constructed on the site of older buildings, possibly the hall of the original castle. The outer windows of the hall and the ranges look out across the landscape and would have been quite prominent when first built.

On the southern side of the hall is a range comprising cellars in the basement, and a great chamber and the castle’s chapel above, both approximately 50 by 24 feet (15.2 by 7.3 m) in size. The range on the northern side includes a dining room and winter parlour, lit by a large bay window, bedrooms for the lord’s family, and a large kitchen, two storeys tall and 35 by 29 feet (10.7 by 8.8 m) across.

The service range includes a pantry, larder and servants’ accommodation, alongside the narrow postern gate. The range features an octagonal tower, overlooking the inner ward. A kitchen annex, since destroyed, once existed alongside the south-west edge of the curtain walls, close to the great tower. A garderobe was built into a turret in the north-west side of the curtain wall, and the castle’s well, some 100 feet (30.5 m) deep, lies in the centre of the ward.

The outer ward lay to the north and west of the castle, forming a flat platform, approximately 400 by 650 feet (120 by 200 m) across at its widest extent, that held the supporting infrastructure for the castle. Originally protected with earthwork banks, these were at least partially replaced by a stone wall in the late 16th century. When Dudley Zoo was built in the 20th century, the edges of the ward were largely cut away or occupied by modern buildings.

Bibliography

- Blockside, E. (1885). An Illustrated Guide to Dudley Castle and Priory, with a Short General History from the Earliest Period. Dudley, UK: E. Blockside.

- Booker, Luke. (1825). A Descriptive and Historical Account of Dudley Castle, and Its Surrounding Scenery. Dudley, UK: J. Hinton.

- Brakspear, Harold. (1914). “Dudley Castle” The Archaeological Journal Vol. 71 pp. 1-24.

- Fryde, Natalie. (2003). The Tyranny and Fall of Edward II 1321-1326. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Goodall, John. (2011). The English Castle, 1066-1650. New Haven, US and London, UK: Yale University Press.

- Harris, William. (1845). Rambles About Dudley Castle. Dudley, UK: Hales-Owen.

- Higham, Robert and Philip Barker. (1992) Timber Castles. London, UK: Batsford.

- Hislop, M. (2010). “A missing link: a reappraisal of the date, architectural context and significance of the great tower of Dudley Castle.” Antiquaries Journal Vol. 90 pp. 211-233.

- Manganiello, Stephen C. (2004). The Concise Encyclopedia of the Revolutions and Wars of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1639-1660. Lanham, US: The Scarecrow Press.

- Mckenna, Joseph (2012). A Journal of the English Civil War: The Letter Book of Sir William Brereton, Spring 1646. Jefferson: US: McFarland and Company.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville (1994). The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Rickard, John. (2002). The Castle Community: The Personnel of English and Welsh Castles, 1272-1422. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press..

- Simpson, W.D. (1939). “The Castles of Dudley and Ashby de la Zouche.” The Archaeological Journal Vol. 96 p. 141-154.

- Simpson, W.D. (1944). “Dudley Castle; the Renaissance buildings.” The Archaeological Journal Vol. 101 pp. 119-125.

- Tappin, Stuart and David Platts. (2015) “Conservation of Tecton Buildings at Dudley Zoo, West Midlands.” ASCHB Transactions. Vol. 38 pp. 12-28.

Attribution

The text of this page is licensed under under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Photographs on this page include those drawn from the British Museum, Geograph and the Flickr websites, as of 19 August 2019, and attributed and licensed as follows: “Castle Keep“, author Gordon Griffiths, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; adapted from “Dudley“, author Nigel Renny, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Flying the Flag at Dudley Castle“, author Matt Johnson, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Dudley Castle Grounds“, author William Pearce, released under CC BY-ND 2.0; “Dudley Castle“, author Peter Lowe, released under CC BY-ND 2.0; “Token“, photograph copyright Trustees of the British Museum, released under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.