Academics have studied English and Welsh castles for many years, examining their military, political and social roles. This article presents a historiography of this work, and some of the key texts from each period. It also describes some of the academic journals and other sources available for those studying castles.

Historiography

Antiquarian period

For several centuries, castles were primarily the subject of antiquarian study. The 16th-century writer John Leland, for example, travelled across England, recording and collecting information on many of our castles. Subsequent researchers with an interest in the past, and a willingness to search out and collect medieval or early modern works, assembled a body of knowledge on many of the major fortifications in the UK.

The resulting histories were less rigorous than their modern equivalents, and had to largely rely on documentary and oral traditions, however, rather than archaeological investigations. In many cases, a history of a castle was combined with the history of its aristocratic family, who often financially supported the publication.

Antiquarian research informed the early guidebooks that began to appear in the early 19th century in response to the growing numbers of visitors. It also fed into the debates within local and national societies, who met to discuss or to visit particular locations.

During the Victorian period, writers such as George T. Clark began to bring greater structure to investigations, combined with a sharper focus on the physical remains of castles. Clark’s Mediaeval Military Architecture, for example, represented a breakthrough in terms of the level of detail recorded and the accuracy of its descriptions. Clark and his contemporaries were able to bring architectural and engineering skills to bear on the analysis of castles – and, increasingly, photography began to be used as a way of recording the remains.

- Clark, George T. (1884) Mediaeval Military Architecture. London, UK: Wyman and Sons.

- Mackenzie, James D. (1896) The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure, Vol II. New York, US: Macmillan.

Early professional studies

The turn of the 20th century saw increasing professional academic interest in castle studies. Ella Armitage’s 1912’s book The Early Norman Castles of the British Isles provided a rigorous survey of the country’s sites, while arguing convincingly that castles were introduced to England by the Normans, rather than representing an Anglo-Saxon tradition, as had previously been thought. Indeed, Armitage’s definition of a castle, which generally excluded pre-Norman works, set the boundaries of the discipline for much of the next century

Alexander Thompson also published Military Architecture in the same year, an influential work which suggested an evolution of English castles through the Middle Ages. Thompson regarded castles as bound up with development of military science: earth and timber castles gave way to better, stronger stone castles; round towers replaced square towers; concentric Edwardian castles surpassed simpler stone defences; gunpowder ultimately made castles redundant. Thompson’s narrative was again heavily influential for many years.

- Armitage, Ella. (1912) The Early Norman Castles of the British Isles. London, UK: John Murray.

- Thompson, Alexander. (1912) Military Architecture in England during the Middle Ages. London, UK: H. Frowde.

- Oman, Charles. (1926) Castles. London, UK: Great Western Railway.

Post-war military studies

After the Second World War the historical analysis of British castles was dominated by Arnold Taylor, R. Allen Brown and D. J. Cathcart King. These academics made use of a growing amount of archaeological evidence, as the 1940s saw an increasing number of excavations of motte and bailey castles, and the number of castle excavations as a whole went on to double during the 1960s.

With an increasing number of castle sites under threat in urban areas, a public scandal in 1972 surrounding the development of the Baynard’s Castle site in London contributed to reforms and a re-prioritisation of funding for rescue archaeology. Despite this the number of castle excavations fell between 1974 and 1984, with the archaeological work focusing on conducting excavations on a greater number of small-scale, but fewer large-scale sites.

Social and political history played a stronger role in post-war studies, drawing on wider breakthroughs in understanding the dynamics of the medieval economy. Nonetheless, the study of British castles remained primarily focused on analysing their military role, still drawing on the evolutionary model of improvement put forward by Thompson earlier in the century.

- Brown, R. Allen. (1962) English Castles. London, UK: Batsford.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville. (1990) The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political history. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Emery, Anthony. (2006) Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: Volume 1, Southern England. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Cultural revisionism

In the 1990s a wide-reaching reassessment of the interpretation of British castles took place. A vigorous academic discussion over the history and meanings behind Bodiam Castle took place – was the moated castle primarily to be understood as a formidable fortification, intended to protect against a French invasion, or as a landscaped, luxurious private house, built by a self-made, up-and-coming nobleman?

The discussion sparked a wider debate, which concluded that many features of castles previously seen as primarily military in nature were in fact constructed for reasons of status and political power. The Norman’s square stone keeps, for example, were not necessarily constructed because they were a military improvement on their earthwork and timber predecessors, but because the Norman elite could use them to host elaborate political rituals, reinforcing their new claim to power.

As gthe historian Robert Liddiard has described it, the older paradigm of “Norman militarism” as the driving force behind the formation of Britain’s castles was replaced by a model of “peaceable power”. Similar arguments were applied to the remainder of the medieval period: watchtowers were reinterpreted as viewing platforms looking over their owner’s newly emparked lands, and defensive lakes were reconsidered for their value as aesthetic features.

The next twenty years was characterised by an increasing number of major publications on castle studies, examining the social and political aspects of the fortifications, as well as their role in the historical landscape. Although not unchallenged, this “revisionist” perspective remains the dominant theme in the academic literature today.

- Creighton, O. H. (2002) Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England. London, UK: Equinox.

- Liddiard, Robert. (2005) Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500. Macclesfield, UK: Windgather Press.

- Wheatley, Abigail. (2004) The Idea of the Castle in Medieval England. York, UK: York Medieval Press.

Guides, studies and journals

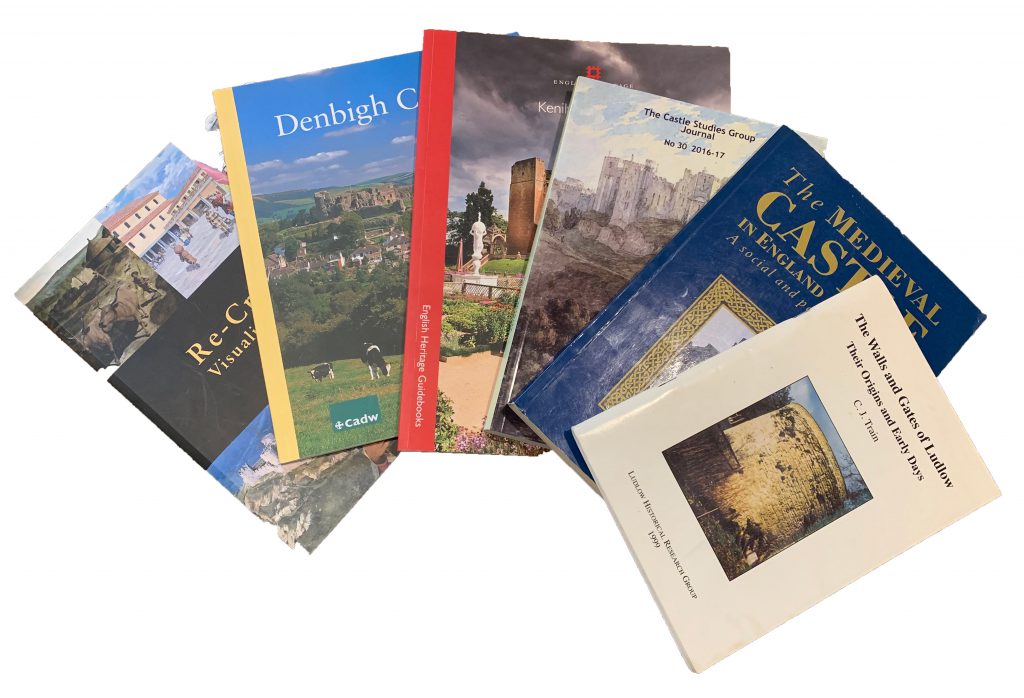

The Ministry of Works began to publish historical and architectural guidebooks soon after the ministry began to build up the collection of buildings in the nation’s care. The ministry’s successor, the Ministry of the Environment continued the practice, as have English Heritage and Cadw, the English and Welsh heritage agencies that took over the respective collections in 1984.

The guidebooks are written by leading scholars and comparisons of the volumes over time can illustrate the changing interpretations of different sites.

Before the separation of English Heritage and Historic England in 2015, English Heritage also published a range of ad hoc research papers and ran an academic journal, The English Heritage Historical Review, between 2006 and 2014. An eight-volume history of the National Heritage Collection (covering the period from 1883-1983) was published in 2015 and provides some rare insights into the transition of many castles from private to public ownership.

Other relevant journals include:

- The Castle Studies Group Journal is published annually by the group, and provides a rich source of articles and digests on recent work across the UK.

- Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale is a European journal, named after the “Château Gaillard” conferences, first started in 1962 by Michael de Bouard. The journals publishes in English, German and French, and is one of the leading voices in research into European castles.

- Medieval Archaeology is the journal of the Society for Medieval Archaeology. In addition to articles on particular aspects of castles, its annual roundup of medieval archaeology (“Medieval England in…”) often has valuable insights.

- FORT, the journal of the Fortress Study Group, sometimes covers late medieval fortifications.

Attribution

The text of this page is licensed under under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Photographs on this page include those drawn from the Wikimedia and Flickr websites, as of 7 October 2018, and attributed and licensed as follows: “George Thomas Clark” (Public Domain); “Ancient slide film 1981-2 (Coppergate)“, author alh1, released under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0; “Bodiam-castle-10My8-1197“, author WyrdLight.com, released under CC BY-SA 3.0.