Winchester Castle was built by William fitzOsbern in 1067, in the south-west corner of Winchester’s city walls. Winchester was then one of the most important cities in England and the castle became a major royal fortress, protected in stone and used as a residence by visiting monarchs. It played a role in the civil wars of the Anarchy in the 12th century and both the First and Second Barons’ Wars in the 13th.

Henry III invested huge sums in the castle, building stronger walls and turning the interior into a luxurious palace. While his son, Edward I, was visiting in 1302, however, the castle caught fire and was never fully repaired. Kings preferred to stay at Wolvesey Castle when visiting Winchester and the fortress fell into disrepair. The Great Hall in the lower ward of the castle became the centre of county administration.

During the English Civil War in the 1640s, Winchester Castle was held by both the Royalists and Parliamentarians. After the conflict, Parliament ordered it to be slighted and much of the walls were pulled down in 1651. Charles II began to redevelop the ruins to create a terraced mansion called King’s House, but the work was never completed. The building was first used as a prison, and then as a barracks, while the Great Hall remained in use as a law court.

In the 21st century, the majority of the castle site is used for residential purposes, after the redevelopment of the barracks in 1994. The Great Hall was last used as a court in 1974, and is now open to visitors. It houses the huge Round Table, which probably dates from the 13th century and is 5.5 m (18 ft) in diameter, painted with an Arthurian design,

History

11th-12th centuries

Winchester Castle was built in 1067 by William fitzOsbern, soon after the Norman invasion of England. Winchester was then the administrative centre of the kingdom, holding the royal treasury and the governmental records. It surrendered to William the Conqueror in November 1066, and early the next year the King ordered the construction of a castle, under the supervision of fitzOsbern, an important Norman lord.

The castle was built in the south-west corner of the city, which was already protected by an ancient set of city walls. The site occupied a salient overlooking the rest of the city, and around 60 houses had to be demolished to make way for the work. Winchester Castle was 1.6 hectares (4 acres) in size, initially with a large motte at the northern end, and possibly a larger mound at the southern end. At first the castle was protected with wooden ramparts, which were soon replaced in stone.

By around 1100, the castle had superseded the royal palace in the city itself, and became a royal residence – the palace passed to the bishops of Winchester. A stone keep was built on the northern motte in the early 12th century. The early castle contained a royal chapel and probably a hall, apartments, and a prison.

In 1135, the succession to the Crown was disputed, leading to the civil war, known as the Anarchy, between the followers of King Stephen and the Empress Matilda. Winchester Castle was initially held for Stephen by William of Pont de l’Arche. In 1141, the Bishop of Winchester, Henry of Blois, changed sides and gave the castle to the Empress. He changed sides again soon after, placing Matilda and the castle under siege. Eventually the Empress retreated from the castle, which returned to the control of Stephen.

Winchester Castle was reinforced under Henry II, who inherited the throne after the death of Stephen. Extensive work was also carried out on the royal accommodation, and the castle was used to detain Queen Eleanor after she sided against Henry in the rebellion of 1173-74. The total cost of the work was £1,250, the sixth-largest sum invested in any of Henry’s castles. The castle was increasingly less significant as an administrative centre, however, as Westminster was now used to hold the royal treasury. 1It is difficult to accurately compare medieval financial figures with modern equivalents. See our article on medieval money for more details.

13th-15th centuries

King John often used the castle, and it became involved in the First Barons’ War in 1216. Winchester Castle had been held by the Crown, but it was soon attacked by the rebel barons and Prince Louis of France. The siege took two weeks, during which the walls were broken down with siege engines and the ditches filled up to enable an assault. It was held by the rebels until 1217, when royalist supporters of the young Henry III retook it.

The castle was greatly developed during Henry III’s reign. Early on, his government repaired the damage done during the First Barons’ War, and built a new circular tower at the north end in 1222. The great gate and its bridge were rebuilt in 1243, the protective ditch widened, and by 1258 all the eastern towers had been reconstructed, at a total cost of £6,000. 2It is difficult to accurately compare medieval financial figures with modern equivalents. See our article on medieval money for more details. The result would have been an impressive fortification and an important symbol of royal authority.

Inside the walls, the castle was also transformed. Henry used the castle frequently, and reconstructed the Great Hall, building new chambers for himself and Queen Eleanor. Henry was a pious, religious man, and extended the existing three chapels and building several more. The work cost around £4,000, creating a luxurious royal residence. 3It is difficult to accurately compare medieval financial figures with modern equivalents. See our article on medieval money for more details.

During the Second Barons’ War, the castle withstood siege by Simon de Montfort and the rebel barons in 1265. Winchester Castle was then kept well repaired by Henry’s son, Edward I. In 1302, however, the King and Queen were almost killed in a serious fire in the royal apartments. The chambers were never repaired, probably because of the cost involved, and subsequent kings stayed at nearby Wolvesey Castle, owned by the bishops of Winchester.

Although Winchester Castle was maintained during the rest of the 14th century, in subsequent years it fell into disrepair. The royal gaol in the castle continued in use, including to hold Scottish and Welsh hostages, and the Great Hall formed the centre for the administration of the county and, on occasion, for sessions of the English Parliament and council of state.

16th-17th centuries

Elizabeth I passed control of the castle to the city of Winchester, who rented out the ditches and the interior of the fortification for grazing castle. The Great Hall continued in use for the county administration, but the gaol was closed in 1575 and redeveloped as a “house of correction” for 80 poor men and women, and also used for holding recusants, a term for those who declined to follow the teachings of the Church of England.

Under James I and Charles I, the castle began to be held by a sequence of private individuals. Between 1607 and 1629, Winchester Castle was granted by the Crown to Sir Benjamin Tichborne and his son. Sir Richard Weston, the lord treasurer, developed the inner ward from 1631 onwards, probably to create a grand private house, and had plans to convert the Great Hall into stables. He died in 1635 and his son abandoned the project, giving the castle back to the Crown. Sir William Waller was granted the property in 1638, and sold the Great Hall for £100 to the county authorities. 4It is difficult to accurately compare early modern financial figures with modern equivalents. See our article on medieval money for more details.

In 1642, civil war broke out between the followers of Charles I and Parliament. Waller, as the Member of Parliament for Andover, sided with the latter. Initially Winchester was held by Royalist forces, but Waller took the castle that December. In 1643, Sir William Ogle retook the castle and held it against Waller when he counter-attacked in March 1644.

In September 1645, Oliver Cromwell, the Parliamentary leader, took the city of Winchester and besieged Ogle in the castle. After a week’s bombardment, the north wall of the castle was badly damaged, and the garrison surrendered on 6 October.

In 1649, the Council of State ordered that the castle be slighted – damaged so as to put it beyond military use. The county authorities were not keen on this plan, and after some delay, Richard Major carried out the work in 1651. Waller sold the ruins to the city of Winchester for £255. 5It is difficult to accurately compare early modern financial figures with modern equivalents. See our article on medieval money for more details.

Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660 and visited Winchester in 1682. He proposed to build a palace there, with an adjacent park for hunting, and the castle was site was given to him by the city for the purpose. Work began under Sir Christopher Wren and in 1683 the remains of the medieval castle were cleared away, leaving only the Great Hall. The palace formed a three-sided courtyard, overlooking the town, and would have a great terrace falling away down to the cathedral below.

By the time of Charles’ death in 1685, the exterior of the palace had been completed, but his successor, James II, curtailed the project. William of Orange and Mary showed little interest in Winchester. Queen Anne considered turning the palace into a residence for her consort, Prince George of Denmark, but ultimately nothing came of the plans.

18th-21st centuries

The unfinished building became known as the King’s House, and in 1756 was turned into a prison, holding 5,000 French soldiers in the Seven Years’ War, 6,500 French and Spanish prisoners in the American War of Independence. In the early 1790s, it housed 700 clergy who had fled the revolution in France. The War Office was keen to take over the building, but George III refused to give up the site.

Finally, in 1793, King’s House was transferred to the Barracks Department, as a convenient location for holding soldiers before they were sent overseas from the south coast. The south end of the old castle was flattened in 1797 to create a parade ground, and between 1809 and 1811 the first floor of the building was split into two levels, enabling King’s House to hold 1,700 men.

In 1837, as part of a deal with the Board of Ordnance, the London and Southampton Railway Company filled in the west side of the castle’s ditch, creating a new parade ground. More building work followed in 1856, when a new officer’s mess was constructed at the south end of the castle, and a hospital erected. The barracks were occupied by the Rifles Brigade, and in 1858 became the Rifle Depot.

On December 1894, King’s House was destroyed by fire – the blaze broke out in the middle of the night, and what water was available to fight the fire was used to protect the Great Hall. The shell of the house was demolished and replaced with two barrack buildings in a similar late-17th century style.

The barracks were redeveloped between 1962 and 1964, being retitled the Peninsula Barracks, and used as the Green Jackets Brigade Depot, the successor to the Rifles. The barracks were closed in 1985 and the site was sold for residential development in 1994.

The Great Hall had continued in use as a law court, with the Crown Court being held in the west end, and the Nisi Prius Court at the other. The interior of the hall was rebuilt in 1765 to support this arrangement, before being cleared in 1871 when new courts were built just to the east, over the old castle ditch. These suffered from subsidence and the Crown Court returned to the Great Hall between 1938 and 1974. The outside of the Great Hall was cleared of adjacent buildings in the 1970s, as part of the work to construct a replacement court house, again just to the east of the hall.

Architecture

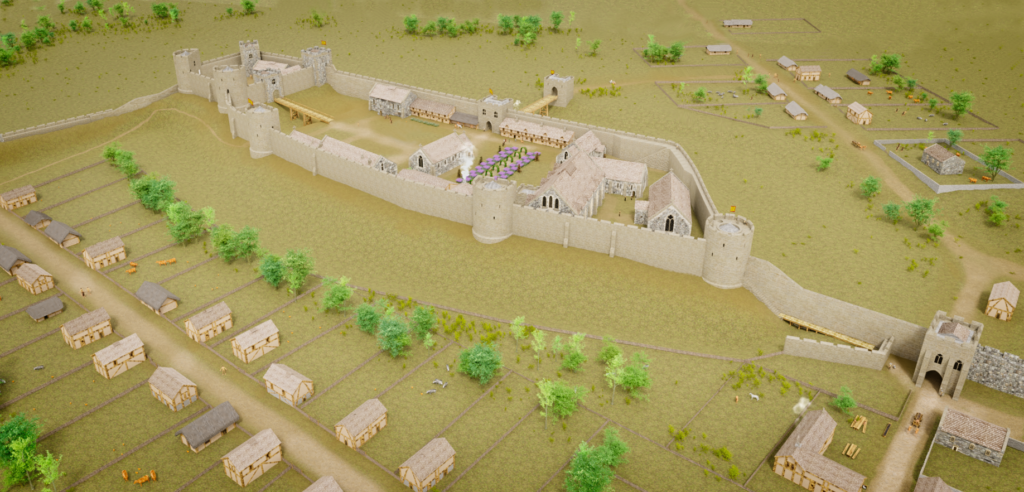

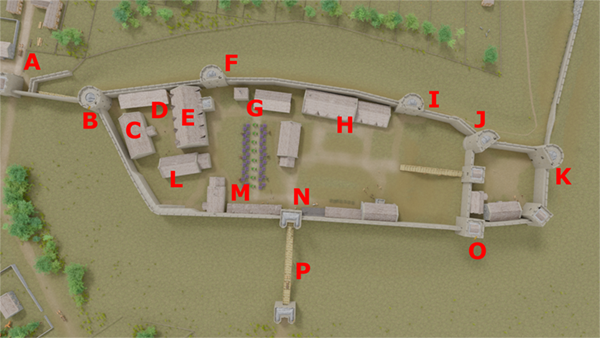

Winchester Castle was built in the south-west corner of Winchester, in the highest part of the walled city. The original site was around 1.6 hectartes (4 acres) in size with an upper and a lower ward, the latter stretching down towards West Gate and the city walls.

Almost nothing of the medieval castle survives today, but it would have been constructed in several phases. The early castle had mottes at both the north and south ends of the castle, the northern earthwork supporting a square keep. In the 13th century, the north motte was flattened, and the defences largely rebuilt. The only surviving parts of the castle is the Great Hall, and the excavated foundations of two of the 13th-century circular towers.

The Great Hall

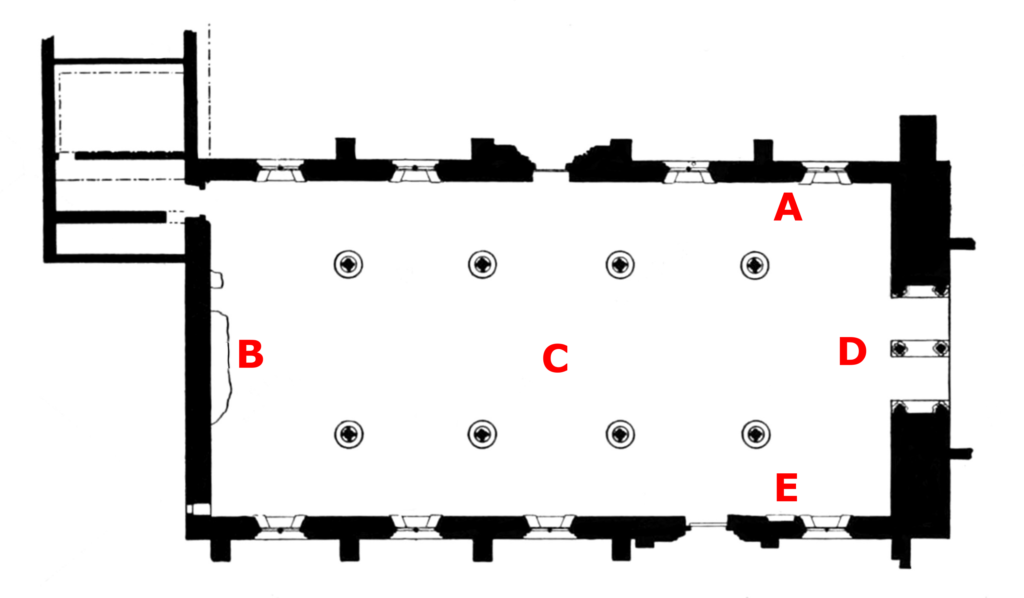

The Great Hall was built between 1222 and 1235. It was 31 m (111 ft) by 15.5 m (55 ft) across, with a central nave lined with marble columns, and aisles and windows on either side forming bays.

The Great Hall has been altered and adapted over the centuries. When first built, the roofs of the aisles were lower, and each of the windows had a circular light above it; the roof of the main hall was more steeply pitched. The hall was entered by a main door on the north side. There would have been a dais for the king and queen at the west end, with a large painting of the Wheel of Fortune above them, and the hall would have been elaborately painted, including a large, circular map of the world on the wall opposite the royal couple.

The hall was adapted between 1348 and1349, giving the roof its current form. There were originally service doors in the eastern bay, since blocked, which led to the buttery, pantry, saucery and great kitchen. The main door was blocked up in 1789, and a new door and porch constructed in the central bay, which was rebuilt again in 1845. It was reroofed by T. H. Wyatt during his work in the 1870s, and restored once again between 1975 and 1976. The roof was renovated again in 1996.

Prominently displayed on the wall at the west of the hall is the Round Table, also known as “King Arthur’s Round Table”. It was probably constructed in the 13th century, early in the reign of King Edward. Edward was interested in the legends of King Arthur and may have first used it in 1290, when he held a huge dinner at Winchester in an Arthurian style. Initially the table was placed on the floor of the hall, before being hung on the east wall in 1348, and then moved to its current location in 1873.

The table is 5.5 m (18 ft) in diameter, weighting 1,200 kg (1 ton 4 cwt), and constructed of 121 pieces of oak. It would have originally been unpainted, but was then decorated with its current design by Henry VIII in 1516, to show King Arthur and the names of 24 of his knights, with Arthur resembling Henry himself. The table was repainted again to the same design by William Cave in 1789.

Queen Eleanor’s Garden

To the south of the Great Hall is Queen Eleanor’s Garden, a recreation of one of the 13th century garden that would have been planted within the castle. Although the location is not authentic – this part of the castle would not have been used as a garden – the design of the herber garden is otherwise historically accurate. It was opened in 1986 by the Queen Mother.

Bibliography

- Biddle, Martin and Beatrice Clayre. (2000) Winchester Castle, the Great Hall and Round Table. Hampshire County Council: Winchester, UK.

- Biddle, Martin, Sally Badham and A.. C. Barefoot. (2000). King Arthur’s Round Table: An Archaeological Investigation. Boydell Press.

- Cunliffe, Barry. (1962) “The Winchester City Wall,” Hampshire Field Club Proceedings, Volume 22.

- Kynan-Wilson, William. (2021) Henry of Blois: New Interpretations. Boydell and Brewer.

- Wareham, John. (2000) Three Palaces of the Bishops of Winchester: Wolvesey (Old Bishop’s Palace), Hampshire; Bishop’s Waltham Palace, Hampshire; Farnham Castle Keep, Surrey. English Heritage: London, UK

Attribution

The text of this page is licensed under under CC BY-NC 2.0. The photographs include those from the Flickr, Ancestry Images, and Geograph websites, and are attributed as follows: “The Great Hall“, author Terry Hassan, released under CC BY-NC 2.0; “Foundations of the castle“, author Stephen Mackay, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “The Round Table“, author Mario Sanchez Prada, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Eleanor’s garden“, author Jim Linwood, released under CC BY 2.0, “King’s House“, photograph copyright AncestryImages.com, released for non-commercial use.