Winchester’s city walls date from the Roman period, when they encircled an area of 58 hectares (144 acres). Adapted for use by the Anglo-Saxons to provide protection against Viking invasions, they were used in turn by the Normans after the invasion of 1066.

The medieval walls had five major gatehouses and one postern gate. Extensively rebuilt in the 12th century, the walls were then maintained through murage grants. They were reinforced during the second half of the 14th century in response to the threat of French invasion and peasant revolt.

After the 17th century, the walls and gatehouses were no longer needed for defence. As Winchester grew and more traffic entered the city, the walls were largely torn down and the gatehouses dismantled. In the 21st century, only small sections remain, along with the gatehouses of Westgate and Kingsgate.

History

1st – 10th centuries

Winchester’s city walls were first erected in the Roman period, when the town was known as Venta Belgarum. The town was founded around 70 CE around a grid pattern, which was initially protected by earth and timber ramparts. Early in the 3th century, the defences were rebuilt in stone, enclosing an area of 58 hectares (144 acres). Although Winchester was the fifth largest Roman city in Britain, it went into decline after the fall of empire and was largely abandoned.

The Old Minster Cathedral was established in Winchester in 642 and, buoyed up the presence of the bishopric, the city recovered in size to become the capital of Wessex. The old Roman south gate was blocked up in either the 7th or 8th century.

The Viking threat grew in the first half of the 9th century, but by then the city defences had fallen into ruin: in 868, they were derisively referred to as the “King’s city hedge” in one document. As a result of this, the Vikings were able to raid Winchester in 860 without any significant opposition.

In response to the threat, Alfred the Great replanned the streets of Winchester during the 880s. He repaired the walls and constructed new gatehouses, probably on the same sites as earlier Roman ones, reopening the south gate and digging and protective ditches. The result was a powerful Anglo-Saxon burh, or fortified town; 2,400 hides of land, a measurement of land through which taxes were gathered, were recorded as being needed to support the defences. Probably as a result, Winchester survived the subsequent Viking invasions intact.

11th – 15th centuries

By the time of the Norman invasion of 1066, Winchester was the administrative centre of the kingdom, holding the royal treasury and the governmental records. In the wake of the Battle of Hastings, Winchester surrendered to William the Conqueror in November. The south-west salient of the Anglo-Saxon walls was confiscated by the Crown and used to construct Winchester Castle, intended to control the occupied city.

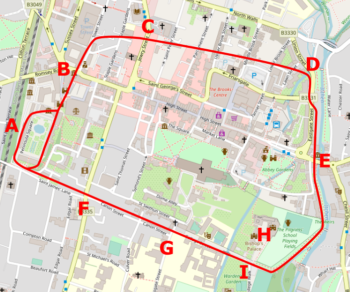

The Normans, and in particular Henry I, maintained the city defences, and the medieval walls followed the older Roman and Anglo-Saxon route, with gates at Westgate, Kingsgate, Eastgate, Northgate, Southgate and Durngate – the latter a postern gate. Each of the gates had a chapel associated with it, and blacksmiths set up close to the gates, presumably to shoe the horses of travellers. An intramural lane ran around the city, following the line of its Anglo-Saxon predecessor. A protective ditch surrounded the walls; near the Westgate, this was 40 m (131 ft) wide and 12 m (39 ft) deep.

Within the city, Winchester Cathedral was also walled and protected with its own gatehouses, and parts of its walls formed part of the external defences. Wolvesey Castle, belonging to the bishops, also had its own walls, and a rear gate was later added to enable access to its estate.

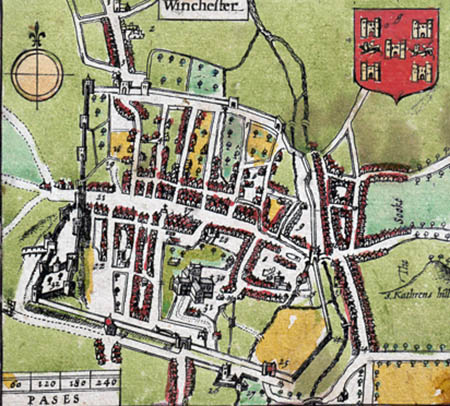

Winchester soon grew beyond its walls. By 1110, surveys showed that the walled city had been joined by a c. 49 hectare (121 acre) settlement to the south, and smaller c. 20 hectare (49 acre) suburbs to the north, east and west. The western settlement, then called Erdberi, grew up within an Iron Age earthwork, re-adapted to provide basic defences. The city seal of 1200 included the walls and the five main gatehouses.

By the 13th century, the old Roman wall was much decayed; the historian Hilary Turner describes it as “little more than a stump”. Work was carried out to renew it by refacing the surviving core of the old wall, although the results were quite thin and insubstantial.

The work was was funded by murage grants from the Crown from 1228 onwards. Some of these were funded through the city authorities, but other sums were parceled out through the the bishops or the cathedral priory. East Gate was supported by murage collected by St Mary’s Abbey, and Greyfriars, established in 1258, took on the responsibility to maintain the walls adjacent to its estate.

In the second half of the 14th century, interest in Winchester’s defences increased again. The walls were repaired in 1369 and, in 1377, Durngate was blocked up to increase the security of the defences. With fear of a French invasion during the Hundred Years’ War, bastions were built along the western line of the wall. Westgate was then reinforced in 1390s after the Peasants’ Revolt. Repairs and maintenance of the city walls continued through until the mid-15th century.

16th – 21st centuries

By the 16th century, the medieval walls were increasingly less important for defence. The first floor of Westgate became a city gaol, and although repairs were carried out in 1564 at the expense of the Marquess of Winchester, they became far less frequent. Ivy and weeds became a problem. Nonetheless, John Speed’s map of 1611 shows the walls still encircling the city.

In 1642, civil war broke out between the followers of Charles I and Parliament. Waller, as the Member of Parliament for Andover, sided with the latter. Initially Winchester was held by Royalist forces, but Waller took the town and castle that December. In 1643, Sir William Ogle retook the city and held it against Waller when he counter-attacked in March 1644. In September 1645, Oliver Cromwell, the Parliamentary leader, took the city of Winchester and besieged Ogle in the castle. After a week’s bombardment, the garrison surrendered on 6 October.

The 18th century saw the gradual dismantling and adaption of the defences to new uses. In 1755, the upper floor of Northgate collapsed and the gate was demolished in 1771, along with Southgate. Eastgate was pulled down in 1791 to make way for increased traffic into the city, and large parts of the wall itself had been destroyed by 1800.

Kingsgate survived because of the chapel above the gate, while Westgate became a pub. In 1742, Westgate had been found to be in poor repair, and three years later the its floor gaol closed, although the lockup on the ground floor continued in used until 1760. The first floor leased by the adjacent Fighting Cocks pub as a “smoking room”. In 1837, the Fighting Cocks was pulled down and rebuilt as the larger Plume and Feathers – still attached to the gatehouse -and the first floor of Westgate was used for holding Winchester’s court and city records, before becoming a museum in 1898.

Increasing traffic levels continued to prove a problem, and in 1937 the Plume and Feathers was purchased by the Winchester County Council in 1937. The pub and houses on either side of Westgate were pulled down in 1940, the gatehouse extensively restored, and the increased space used for road traffic from 1958 onwards.

In the 21st century, the remains of the wall and gatehouses are protected under UK law as Scheduled Monuments and Grade I listed buildings. Westgate is open to the public as part of the city museum.

Architecture

Winchester’s city walls were constructed from limestone rubble, often forming a sequence of layers leading back to the core of the old Roman wall. Most of the circuit has been destroyed, but some parts of the wall survive to the east of Wolvesey Castle, showing both the medieval and Roman stonework, and other fragments exist in houses and gardens across the city. There were two mural towers, again lost.

Only two of the original city gates survive today, Westgate and Kingsgate. Westgate is a two-storey building, much of which dates from the end of 1390. The main arch is original to the building, with the pedestrian access to one side added later. The gatehouse was protected by a porcullis and two early gunports, topped with battlements. The stonework was originally flint, with ashlar quoins, later refaced in placed entirely in ashlar. It had ornamental sculptured heads, and probably displayed the bade of Richard II.

Kingsgate’s current structure dates from the 16th-century, and comprises three archways, supporting a first-storey chapel. Much of the building has been restored or rebuilt over the years. The gatehouse is not defensive in character, unlike Kingsgate.

Visiting Westgate

Bibliography

- Biddle, Martin and Beatrice Clayre. (2000) Winchester Castle, the Great Hall and Round Table. Hampshire County Council: Winchester, UK.

- Biddle, Martin, Sally Badham and A.. C. Barefoot. (2000). King Arthur’s Round Table: An Archaeological Investigation. Boydell Press.

- Creighton, Oliver and Robert Higham. (2004) Medieval Town Walls; An Archaeology and Social History of Urban Defence. Tempus: Stroud, UK.

- Cunliffe, Barry. (1962) “The Winchester City Wall,” Hampshire Field Club Proceedings, Volume 22.

- Turner, Hilary T. (1970) Town Defences in England and Wales. John Baker: London.

Attribution

The text of this page is licensed under under CC BY-NC 2.0. Photographs on this page include those from the Flickr website, and are attributed as follows: “Kingsgate“, author John Stanning, released under CC BY-SA 3.0; adapted from “John Speed’s map of Hampshire“, photograph copyright Cambridge University Library, released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-NC 3.0); and the plan of the Winchester’s town walls, which is based on an underlying map copyright OpenStreetMap contributors, and is released under CC BY-SA 2.0.