Kenilworth Castle is located in the town of the same name in Warwickshire, England. Constructed in phases from Norman through to Tudor times, the castle has been described by architectural historian Anthony Emery as “the finest surviving example of a semi-royal palace of the later middle ages, significant for its scale, form and quality of workmanship”. Kenilworth has also played an important historical role. The castle was the subject of the six-month-long Siege of Kenilworth in 1266, believed to be the longest siege in English history, and formed a base for Lancastrian operations in the Wars of the Roses. Kenilworth was also the scene of the removal of Edward II from the English throne and the Earl of Leicester’s lavish reception of Elizabeth I in 1575.

Kenilworth Castle is located in the town of the same name in Warwickshire, England. Constructed in phases from Norman through to Tudor times, the castle has been described by architectural historian Anthony Emery as “the finest surviving example of a semi-royal palace of the later middle ages, significant for its scale, form and quality of workmanship”. Kenilworth has also played an important historical role. The castle was the subject of the six-month-long Siege of Kenilworth in 1266, believed to be the longest siege in English history, and formed a base for Lancastrian operations in the Wars of the Roses. Kenilworth was also the scene of the removal of Edward II from the English throne and the Earl of Leicester’s lavish reception of Elizabeth I in 1575.

The castle was built over several centuries. Founded in the 1120s around a powerful Norman great tower, the castle was significantly enlarged by King John at the beginning of the 13th century. Huge water defences were created by damming the local streams, and the resulting fortifications proved able to withstand assaults by land and water in 1266. John of Gaunt spent lavishly in the late 14th century, turning the medieval castle into a palace fortress designed in the latest perpendicular style. The Earl of Leicester then expanded the castle once again, constructing new Tudor buildings and exploiting the medieval heritage of Kenilworth to produce a fashionable Renaissance palace.

Kenilworth was partly destroyed by Parliamentary forces in 1649 to prevent it being used as a military stronghold. Ruined, only two of its buildings remain habitable today. The castle became a tourist destination from the 18th century onwards, becoming famous in the Victorian period following the publishing of Sir Walter Scott’s novel Kenilworth in 1821. English Heritage has managed the castle since 1984. The castle is classed as a Grade I listed building and as a Scheduled Monument, and is open to the public.

History

12th century

Kenilworth Castle was founded in the early 1120s by Geoffrey de Clinton, Lord Chamberlain and treasurer to Henry I. The castle’s original form is uncertain. It has been suggested that it consisted of a motte, an earthen mound surmounted by wooden buildings; however, the stone great tower may have been part of the original design. Clinton was a local rival to Roger de Beaumont, the Earl of Warwick and owner of the neighbouring Warwick Castle, and the king made Clinton the sheriff in Warwickshire to act as a counterbalance to Beaumont’s power. Clinton had begun to lose the king’s favour after 1130, and when he died in 1133 his son, also called Geoffrey, was only a minor. Geoffrey and his uncle William de Clinton were forced to come to terms with Beaumont; this set-back, and the difficult years of the Anarchy (1135–54), delayed any further development of the castle.

Henry II succeeded to the throne at the end of the Anarchy but during the revolt of 1173–74 he faced a significant uprising led by his son, Henry, backed by the French crown. The conflict spread across England and Kenilworth was garrisoned by Henry II’s forces; Geoffrey II de Clinton died in this period and the castle was taken fully into royal possession, a sign of its military importance. The Clintons themselves moved on to Buckinghamshire. By this point Kenilworth Castle consisted of the great keep, the inner bailey wall, a basic causeway across the smaller lake that preceded the creation of the Great Mere, and the local chase for hunting.

13th century

Henry’s successor, Richard I, paid relatively little attention to Kenilworth, but under King John significant building resumed at the castle. When John was excommunicated in 1208, he embarked on a programme of rebuilding and enhancing several major royal castles. These included Corfe, Odiham, Dover, Scarborough as well as Kenilworth. John spent £1,115 on Kenilworth Castle between 1210 and 1216, building the outer bailey wall in stone and improving the other defences, including creating Mortimer’s and Lunn’s Towers.1It is difficult to accurately compare early modern financial figures with modern equivalents. See our article on medieval money for more details. He also significantly improved the castle’s water defences by damming the Finham and Inchford Brooks, creating the Great Mere. The result was to turn Kenilworth into one of the largest English castles of the time, with one of the largest artificial lake defences in England. John was forced to cede the castle to the baronial opposition as part of the guarantee of the Magna Carta, before it reverted to royal control early in the reign of his son, Henry III.

Henry III granted Kenilworth in 1244 to Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, who later became a leader in the Second Barons’ War (1263–67) against the king, using Kenilworth as the centre of his operations. Initially the conflict went badly for King Henry, and after the Battle of Lewes in 1264 he was forced to sign the Mise of Lewes, under which his son, Prince Edward, was given over to the rebels as a hostage. Edward was taken back to Kenilworth, where chroniclers considered he was held in unduly harsh conditions. Released in early 1265, Edward then defeated Montfort at the Battle of Evesham; the surviving rebels under the leadership of Henry de Hastings, Montfort’s constable at Kenilworth, regrouped at the castle the following spring. Edward’s forces proceeded to lay siege to the rebels.

The Siege of Kenilworth Castle in 1266 was “probably the longest in English history” according to historian Norman Pounds, and at the time was also the largest siege to have occurred in England in terms of the number of soldiers involved. Simon de Monfort’s son, Simon VI de Montfort, promised in January 1266 to hand over the castle to the king. Five months later this had not happened, and Henry III laid siege to Kenilworth Castle on 21 June. Protected by the extensive water defences, the castle withstood the attack, despite Edward targeting the weaker north wall, employing huge siege towers and even attempting a night attack using barges brought from Chester. The distance between the royal trebuchets and the walls severely reduced their effectiveness, and heavier trebuchets had to be sent for from London. Papal intervention through the legate Ottobuono finally resulted in the compromise of the Dictum of Kenilworth, under which the rebels were allowed to re-purchase their confiscated lands provided they surrendered the castle; the siege ended on 14 December 1266. The water defences at Kenilworth influenced the construction of later castles in Wales, most notably Caerphilly.

Henry granted Kenilworth to his son, Edmund Crouchback, in 1267. Edmund held many tournaments at Kenilworth in the late 13th century, including a huge event in 1279, presided over by the royal favourite Roger de Mortimer, in which a hundred knights competed for three days in the tiltyard in an event called “the Round Table”, in imitation of the popular Arthurian legends.

14th century

Edmund Crouchback passed on the castle to his eldest son, Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, in 1298. Lancaster married Alice de Lacy, which made him the richest nobleman in England. Kenilworth became the primary castle of the Lancaster estates, replacing Bolingbroke, and acted as both a social and a financial centre for Thomas. Thomas built the first great hall at the castle from 1314 to 1317 and constructed the Water Tower along the outer bailey, as well as increasing the size of the chase. Lancaster, with support from many of the other English barons, found himself in increasing opposition to Edward II. War broke out in 1322, and Lancaster was captured at the Battle of Boroughbridge and executed. His estates, including Kenilworth, were confiscated by the crown. Edward and his wife, Isabella of France, spent Christmas 1323 at Kenilworth, amidst major celebrations.

In 1326, however, Edward was deposed by an alliance of Isabella and her lover, Roger Mortimer. Edward was eventually captured by Isabella’s forces and the custody of the king was assigned to Henry, Earl of Lancaster, who had backed Isabella’s invasion. Henry, reoccupying most of the Lancaster lands, was made constable of Kenilworth and Edward was transported there in late 1326; Henry’s legal title to the castle was finally confirmed the following year. Kenilworth was chosen for this purpose by Isabella probably both because it was a major fortification, and also because of the symbolism of its former owners’ links to popular ideals of freedom and good government. Royal writs were issued in Edward’s name by Isabella from Kenilworth until the next year. A deputation of leading barons led by Bishop Orleton was then sent to Kenilworth to first persuade Edward to resign and, when that failed, to inform him that he had been deposed as king. Edward formally resigned as king in the great hall of the castle on 21 January 1327. As the months went by, however, it became clear that Kenilworth was proving a less than ideal location to imprison Edward. The castle was in a prominent part of the Midlands, in an area that held several nobles who still supported Edward and were believed to be trying to rescue him. Henry’s loyalty was also coming under question. In due course, Isabella and Mortimer had Edward moved by night to Berkeley Castle, where he died shortly afterwards. Isabella continued to use Kenilworth as a royal castle until her fall from power in 1330.

Henry of Grosmont, the Duke of Lancaster, inherited the castle from his father in 1345 and remodelled the great hall with a grander interior and roof. On his death Blanche of Lancaster inherited the castle. Blanche married John of Gaunt, the third son of Edward III; their union, and combined resources, made John the second richest man in England next to the king himself. After Blanche’s death, John married Constance, who had a claim to the kingdom of Castile, and John styled himself the king of Castile and León. Kenilworth was one of the most important of his thirty or more castles in England. John began building at Kenilworth between 1373 and 1380 in a style designed to reinforce his royal claims in Iberia. John constructed a grander great hall, the Strong Tower, Saintlowe Tower, the state apartments and the new kitchen complex. When not campaigning abroad, John spent much of his time at Kenilworth and Leicester, and used Kenilworth even more after 1395 when his health began to decline. In his final years, John made extensive repairs to the whole of the castle complex.

15th century

Many castles, especially royal castles, were left to decay in the 15th century; Kenilworth, however, continued to be used as a centre of choice, forming a late medieval “palace fortress”. Henry IV, John of Gaunt’s son, returned Kenilworth to royal ownership when he took the throne in 1399 and made extensive use of the castle. Henry V also used Kenilworth extensively, but preferred to stay in the Pleasance, the mock castle he had built on the other side of the Great Mere. According to the contemporary chronicler John Strecche, who lived at the neighbouring Kenilworth Priory, the French openly mocked Henry in 1414 by sending him a gift of tennis balls at Kenilworth. The French aim was to imply a lack of martial prowess; according to Strecche, the gift spurred Henry’s decision to fight the Agincourt campaign. The account was used by Shakespeare as the basis for a scene in his play Henry V.

English castles, including Kenilworth, did not play a decisive role during the Wars of the Roses (1455–85), which were fought primarily in the form of pitched battles between the rival factions of the Lancastrians and the Yorkists. With the mental collapse of King Henry VI, Queen Margaret used the Duchy of Lancaster lands in the Midlands, including Kenilworth, as one of her key bases of military support. Margaret removed Henry from London in 1456 for his own safety and until 1461, Henry’s court divided almost all its time among Kenilworth, Leicester and Tutbury Castle for the purposes of protection. Kenilworth remained an important Lancastrian stronghold for the rest of the war, often acting as a military balance to the nearby castle of Warwick. With the victory of Henry VII at Bosworth, Kenilworth again received royal attention; Henry visited frequently and had a tennis court constructed at the castle for his use. His son, Henry VIII, decided that Kenilworth should be maintained as a royal castle. He abandoned the Pleasance and had part of the timber construction moved into the base court of the castle.

16th century

The castle remained in royal hands until it was given to John Dudley in 1553. Dudley came to prominence under Henry VIII and became the leading political figure under Edward VI. Dudley was a patron of John Shute, an early exponent of classical architecture in England, and began the process of modernising Kenilworth. Before his execution in 1553 by Queen Mary for attempting to place Lady Jane Grey on the throne, Dudley had built the new stable block and widened the tiltyard to its current form.

Kenilworth was restored to Dudley’s son, Robert, Earl of Leicester, in 1563, four years after the succession of Elizabeth I to the throne. Leicester’s lands in Warwickshire were worth between £500–£7002

It is difficult to accurately compare 16th century and modern prices or incomes. Depending on the measure used, £500 in 1563 could equate to either £98,300 (using the retail price index) or £1,320,000 (using the average earnings index). A prosperous member of the gentry might expect an annual income of at least £500 during the period, with a wealthy knight like William Darrell, owning 25 manors, enjoying an annual income of around £2000. but Leicester’s power and wealth, including monopolies and grants of new lands, depended ultimately on his remaining a favourite of the queen.

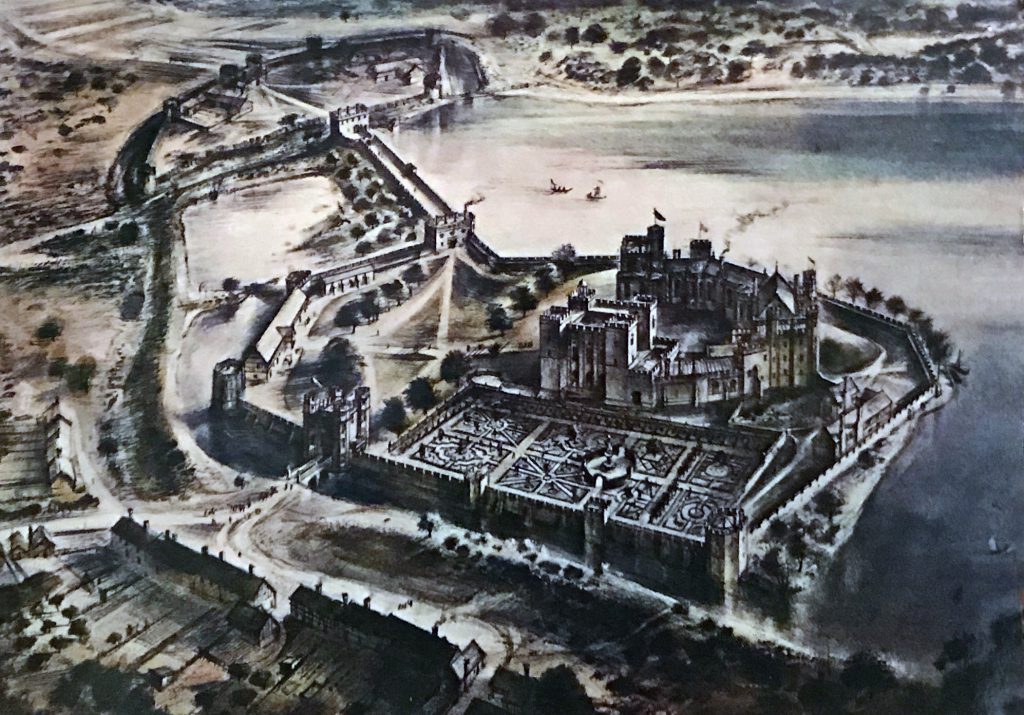

Leicester continued his father’s modernisation of Kenilworth, attempting to ensure that Kenilworth would attract the interest of Elizabeth during her regular tours around the country. Elizabeth visited in 1566 and 1568, by which time Leicester had commissioned the royal architect Henry Hawthorne to produce plans for a dramatic, classical extension of the south side of the inner court. In the event this proved unachievable and instead Leicester employed William Spicer to rebuild and extend the castle so as to provide modern accommodation for the royal court and symbolically boost his own claims to noble heritage. After negotiation with his tenants, Leicester also increased the size of the chase once again. The result has been termed an English “Renaissance palace”.

Elizabeth viewed the partially finished results at Kenilworth in 1572, but the complete effect of Leicester’s work was only apparent during the queen’s last visit in 1575. Leicester was keen to impress Elizabeth in a final attempt to convince her to marry him, and no expense was spared. Elizabeth brought an entourage of thirty-one barons and four hundred staff for the royal visit that lasted an exceptional nineteen days; twenty horsemen a day arrived at the castle to communicate royal messages. Leicester entertained the Queen and much of the neighbouring region with pageants, fireworks, bear baiting, mystery plays, hunting and lavish banquets. The cost was reputed to have amounted to many thousand pounds, almost bankrupting Leicester, though it probably did not exceed £1,700 in reality.3It is difficult to accurately compare 16th century and modern prices or incomes. Depending on the measure used, £1,700 in 1575 could equate to either £324,000 (using the retail price index) or £4,290,000 (using the average earnings index). For comparison, a wealthy knight like William Darrell, owning 25 manors, enjoyed an annual income of around £2000. The event was considered a huge success and formed the longest stay at such a property during any of Elizabeth’s tours, yet the queen did not decide to marry Leicester.

Kenilworth Castle was valued at £10,401 in 1588,4It is difficult to accurately compare 16th century and modern prices or incomes. Depending on the measure used, £10,401 in 1588 could equate to either £2,040,000 (using the retail price index) or £23,300,000 (using the average earnings index). For comparison, £10,401 was almost five times the income of a wealthy knight of the period such as like William Darrell, who owned 25 manors and enjoyed an annual income of around £2000. when Leicester died without legitimate issue and heavily in debt. In accordance with his will, the castle passed first to his brother Ambrose, Earl of Warwick, and after the latter’s death in 1590, to his illegitimate son, Sir Robert Dudley.

17th century

Sir Robert Dudley, having tried and failed to establish his legitimacy in front of the Court of the Star Chamber, went to Italy in 1605. In the same year Sir Thomas Chaloner, governor (and from 1610 chamberlain) to James I’s eldest son Prince Henry, was commissioned to oversee repairs to the castle and its grounds, including the planting of gardens, the restoration of fish-ponds and improvement to the game park. During 1611–12 Dudley arranged to sell Kenilworth Castle to Henry, by then Prince of Wales. Henry died before completing the full purchase, which was finalised by his brother, Charles, who bought out the interest of Dudley’s abandoned wife, Alice Dudley. When Charles became king, he gave the castle to his wife, Henrietta Maria; he bestowed the stewardship on Robert Carey, Earl of Monmouth, and after his death gave it to Carey’s sons Henry and Thomas. Kenilworth remained a popular location for both King James I and his son Charles, and accordingly was well maintained. The most famous royal visit occurred in 1624, when Ben Jonson’s The Masque of Owls at Kenilworth was performed for Charles.

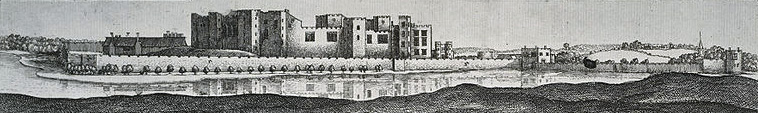

The First English Civil War broke out in 1642. During its early campaigns, Kenilworth formed a useful counterbalance to the Parliamentary stronghold of Warwick. Kenilworth was used by Charles on his advance to Edgehill in October 1642 as a base for raids on Parliamentary strongholds in the Midlands. After the battle, however, the royalist garrison was withdrawn on the approach of Lord Brooke, and the castle was then garrisoned by parliamentary forces. In April 1643 the new governor of the castle, Hastings Ingram, was arrested as a suspected Royalist double agent. By January 1645 the Parliamentary forces in Coventry had strengthened their hold on the castle, and attempts by Royalist forces to dislodge them from Warwickshire failed. Security concerns continued after the end of the First Civil War in 1646, and in 1649 Parliament ordered the slighting of Kenilworth. One wall of the great tower, various parts of the outer bailey and the battlements were destroyed, but not before the building was surveyed by the antiquarian William Dugdale, who published his results in 1656.

Colonel Joseph Hawkesworth, responsible for the implementation of the slighting, acquired the estate for himself and converted Leicester’s gatehouse into a house; part of the base court was turned into a farm, and many of the remaining buildings were stripped for their materials. In 1660 Charles II was restored to the throne, and Hawkesworth was promptly evicted from Kenilworth. The Queen Mother, Henrietta Maria, briefly regained the castle, with the Earls of Monmouth acting as stewards once again, but after her death King Charles II granted the castle to Sir Edward Hyde, whom he later created Baron Hyde of Hindon and Earl of Clarendon. The ruined castle continued to be used as a farm, with the gatehouse as the principal dwelling; the King’s Gate was added to the outer bailey wall during this period for the use of farm workers.

18th and 19th centuries

Kenilworth remained a ruin during the 18th and 19th centuries, still used as a farm but increasingly also popular as a tourist attraction. The first guidebook to the castle, A Concise history and description of Kenilworth Castle, was printed in 1777 with many later editions following in the coming decades.[g] The castle’s cultural prominence increased after Sir Walter Scott wrote Kenilworth in 1821 describing the royal visit of Queen Elizabeth. Very loosely based on the events of 1575, Scott’s story reinvented aspects of the castle and its history to tell the story of “the pathetic, beautiful, undisciplined heroine Amy Robsart and the steely Elizabeth I”. Although considered today as a less successful literary novel than some of his other historical works, it popularised Kenilworth Castle in the Victorian imagination as a romantic Elizabethan location. Kenilworth spawned “numerous stage adaptations and burlesques, at least eleven operas, popular redactions, and even a scene in a set of dioramas for home display”, including Sir Arthur Sullivan’s 1865 cantata The Masque at Kenilworth. J. M. W. Turner painted several watercolours of the castle.

The number of visitors increased, including Queen Victoria and Charles Dickens. Work was undertaken during the 19th century to protect the stonework from further decline, with particular efforts to remove ivy from the castle in the 1860s.

Today

The castle remained the property of the Clarendons until 1937, when Lord Clarendon found the maintenance of the castle too expensive and sold Kenilworth to the industrialist Sir John Siddeley. Siddeley, whose tax accounting in the 1930s had been at least questionable, was keen to improve his public image and gave over the running of the castle, complete with a charitable donation, to the Commissioner of Works. In 1958 his son gave the castle itself to the town of Kenilworth and English Heritage has managed the property since 1984. The castle is classed as a Grade I listed building and as a Scheduled Monument, and is open to the public.

Between 2005–2009 English Heritage attempted to restore Kenilworth’s garden more closely to its Elizabethan form, using as a basis the description in the Langham letter and details from recent archaeological investigations. The reconstruction cost more than £2 million and was criticised by some archaeologists as being a “matter of simulation as much as reconstruction”, due to the limited amount of factual information on the nature of the original gardens. In 2008 plans were put forward to re-create and flood the original Great Mere around the castle. As well as re-creating the look of the castle it was hoped that a new mere would be part of the ongoing flood alleviation plan for the area and that the lake could be used for boating and other waterside recreations.

Architecture and landscape

Although now ruined as a result of the slighting, or deliberate partial destruction, of the castle after the English Civil War, Kenilworth illustrates five centuries of English military and civil architecture. The castle is built almost entirely from local new red sandstone.

Entrance and outer bailey wall

To the south-east of the main castle lie the Brays, a corruption of the French word braie, meaning an external fortification with palisades.5An alternative view is that the name “brays” derives instead from a corruption of the word “bays”, a medieval word describing a sequence of ponds similar to the lake structure at Kenilworth Only earthworks and fragments of masonry remain of what was an extensive 13th-century barbican structure including a stone wall and an external gatehouse guarding the main approach to the castle. The area now forms part of the car park for the castle. Beyond the Brays are the ruins of the Gallery Tower, a second gatehouse remodelled in the 15th century. The Gallery Tower originally guarded the 152-metre (499-foot) long, narrow walled-causeway that still runs from the Brays to the main castle. This causeway was called the Tiltyard, as it was used for tilting, or jousting, in medieval times. The Tiltyard causeway acted both as a dam and as part of the barbican defences. To the east of the Tiltyard is a lower area of marshy ground, originally flooded and called the Lower Pool, and to the west an area once called the Great Mere. The Great Mere is now drained and forms a meadow, but would originally have been a large lake covering around 100 acres (40 ha), dammed by the Tiltyard causeway.

The outer bailey of Kenilworth Castle is usually entered through Mortimer’s Tower, today a modest ruin but originally a Norman stone gatehouse, extended in the late 13th and 16th centuries. The outer bailey wall, long and relatively low, was mainly built by King John; it has numerous buttresses but only a few towers, being designed to be primarily defended by the water system of the Great Mere and Lower Pool. The north side of the outer bailey wall was almost entirely destroyed during the slighting. Moving clockwise around the outer bailey from Mortimer’s Tower, the defences include a west-facing watergate, which would originally have led onto the Great Mere; the King’s gate, a late 17th-century agricultural addition; the Swan Tower, a late 13th-century tower with 16th century additions named after the swans that lived on the Great Mere; the early 13th-century Lunn’s Tower; and the 14th-century Water Tower, so named because it overlooked the Lower Pool.

Inner court

Kenilworth’s inner court consists of a number of buildings set against a bailey wall, originally of Norman origin, exploiting the defensive value of a natural knoll that rises up steeply from the surrounding area. The 12th-century great tower occupies the knoll itself and forms the north-east corner of the bailey. Ruined during the slighting, the great tower is notable for its huge corner turrets, essentially hugely exaggerated Norman pilaster buttresses. Its walls are 5 metres (16 feet) thick, and the towers 30 metres (98 feet) high. Although Kenilworth’s great tower is larger, it is similar to that of Brandon Castle near Coventry; both were built by the local Clinton family in the 1120s. The tower can be termed a hall keep, as it is longer than it is wide. The lowest floor is filled with earth, possibly taken from the earlier motte that may have been present on the site, and is further protected by a sloping stone plinth around the base. The tall Tudor windows at the top of the tower date from the 1570s.

Much of the northern part of the inner bailey was built by the 14th-century noble John of Gaunt between 1372 and 1380. This part of the castle is considered by historian Anthony Emery to be “the finest surviving example of a semi-royal palace of the later middle ages, significant for its scale, form and quality of workmanship”. Gaunt’s architectural style emphasised rectangular design, the separation of ground floor service areas from the upper stories and a contrast of austere exteriors with lavish interiors, especially on the 1st floor of the inner bailey buildings. The result is considered “an early example of the perpendicular style”.

The most significant of Gaunt’s buildings is his great hall. The great hall replaced an earlier sequence of great halls on the same site, and was heavily influenced by Edward III’s design at Windsor Castle. The hall consists of a “ceremonial sequence of rooms”, approached by a particularly grand staircase, now lost. From the great hall, visitors could look out to admire the Great Mere or the inner court through huge windows. The undercroft to the hall, used by the service staff, was lit with slits, similar to design at the contemporary Wingfield Manor. The roof was built in 1376 by William Wintringham, producing the widest hall, unsupported by pillars, existing in England at the time. There is some debate amongst historians as to whether this roof was a hammerbeam design, a collar and truss-brace design, or a combination of the two.6An example of the combination of the curved hammerbeam and right-angled collar and truss-brace design can be seen in this depiction of the roof of Westminster Hall.

There was an early attempt at symmetry in the external appearance of the great hall – the Strong and Saintlowe Towers architecturally act as near symmetrical “wings” to the hall itself, while the plinth of the hall is designed to mirror that of the great tower opposite it. An unusual multi-sided tower, the Oriel, provides a counterpoint to the main doorway of the hall and was intended for private entertainment by Gaunt away from the main festivities on major occasions. The Oriel tower is based on Edward III’s “La Rose” Tower at Windsor, which had a similar function. Gaunt’s Strong Tower is so named for being entirely vaulted in stone across all its floors, an unusual and robust design. The great hall influenced the design of Bolton and Raby castles, while the hall’s roof design became famous and was copied at Arundel Castle and Westminster Hall.

Other parts of the castle built by Gaunt include the southern range of state apartments, Gaunt’s Tower and the main kitchen. Although now extensively damaged, these share the same style as the great hall; this would have unified the appearance of Gaunt’s palace in a distinct break from the more eclectic medieval tradition of design. Gaunt’s kitchen replaced the original 12th-century kitchens, built alongside the great tower in a similar fashion to the arrangement at Conisbrough. Gaunt’s new kitchen was twice the size of that in equivalent castles, measuring nineteen by eight metres (62 by 26 feet).

The remainder of the inner court was built by Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester, in the 1570s. He built a tower now known as Leicester’s building on the south edge of the court as a guest wing, extending out beyond the inner bailey wall for extra space. Leicester’s building was four floors high and built in a fashionable contemporary Tudor style with “brittle, thin walls and grids of windows”. The building was intended to appear well-proportioned alongside the ancient great tower, one of the reasons for its considerable height. Leicester’s building set the style for later Elizabethan country house design, especially in the Midlands, with Hardwick Hall being a classic example. Modern viewing platforms, installed in 2014, provide views from Elizabeth I’s’s former bedroom.

Leicester also built a loggia, or open gallery, beside the great keep to lead to the new formal gardens. The loggia was designed to elegantly frame the view as the observer slowly admired the gardens, and was a new design in the 16th century, only recently imported from Italy.

Base, left-hand and right-hand courts

The rest of Kenilworth Castle’s interior is divided into three areas: the base court, stretching between Mortimer’s Tower and Leicester’s gatehouse; the left-hand court, stretching south-west around the outside of the inner court; and the right-hand court, to the north-west of the inner court. The line of trees that cuts across the base court today is a relatively modern mid-19th century addition, and originally this court would have been more open, save for the collegiate chapel that once stood in front of the stables. Destroyed in 1524, only the chapel’s foundations remain. Each of the courts was designed to be used for different purposes: the base court was considered a relatively public area, with the left and right courts used for more private occasions.

Leicester’s gatehouse was built on the north side of the base court, replacing an older gatehouse to provide a fashionable entrance from the direction of Coventry. The external design, with its symbolic towers and, originally, battlements, echoes a style popular a century or more before, closely resembling Kirby Muxloe and the Beauchamp gatehouse at Warwick Castle. By contrast the interior, with its contemporary wood panelling, is in the same, highly contemporary Elizabethan fashion of Leicester’s building in the inner court. Leicester’s gatehouse is one of the few parts of the castle to remain intact. The stables built by John Dudley in the 1550s also survive and lie along the east side of the base court. The stable block is a large building built mostly in stone, but with a timber-framed, decoratively panelled first storey designed in an anachronistic, vernacular style. Both buildings could have easily been seen from Leicester’s building and were therefore on permanent display to visitors. Leciester’s intent may have been to create a deliberately anachronistic view across the base court, echoing the older ideals of chivalry and romance alongside the more modern aspects of the redesign of the castle.

Garden and landscape

Much of the right-hand court of Kenilworth Castle is occupied by the castle garden. For most of Kenilworth’s history the role of the castle garden, used for entertainment, would have been very distinct from that of the surrounding chase, used primarily for hunting. From the 16th century onwards there were elaborate knot gardens in the base court. The gardens today are designed to reproduce as closely as possible the primarily historical record of their original appearance in 1575, with a steep terrace along the south side of the gardens and steps leading down to eight square knot gardens. In Elizabethan gardens “the plants were almost incidental”, and instead the design focus was on sculptures, including four wooden obelisks painted to resemble porphyry and a marble fountain with a statue of two Greek mythological figures. A timber aviary contains a range of birds. The original garden was heavily influenced by the Italian Renaissance garden at Villa d’Este.

To the north-west of the castle are earthworks marking the spot of the “Pleasance”, created in 1414 by Henry V. The Pleasance was a banqueting house built in the style of a miniature castle. Surrounded by two diamond-shaped moats with its own dock, the Pleasance was positioned on the far side of the Great Mere and had to be reached by boat. It resembled Richard II’s retreat at Sheen from the 1380s, and was later copied by his younger brother, Duke Humphrey of Gloucester, at Greenwich in the 1430s, as well by his son, John of Lancaster at Fulbrook. The Pleasance was eventually dismantled by Henry VIII and partially moved into the left-hand court inside the castle itself, possibly to add to the anachronistic appearance. These elements were finally destroyed in the 1650s.

See also

- Kenilworth Castle: Literature and the Transformation of Topography, 1700–1850

Visiting the castle

Bibliography

- Adams, Simon. (2002) Leicester and the Court: Essays on Elizabethan Politics. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5325-2.

- Allen Brown, Reginald. (1955) “Royal Castle Building in England, 1154–1216,” English Historical Review, lxx (1955).

- Asch, Ronald G. (2004) “A Difficult Legacy. Elizabeth I’s Bequest to the Early Stuarts,” in Jansohn, Christa. (ed) (2004) Queen Elizabeth I: Past and Present. Münster, Germanyr: LIT Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8258-7529-9.

- Cammiade, Audrey. (1972) Elizabeth the First. Whitstable, UK: Latimer Trend. OCLC 614844183.

- Carpenter, Christine. (1997) The Wars of the Roses: Politics and the Constitution in England, c.1437–1509. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31874-7.

- Carpenter, David. (2004) The Struggle for Mastery: The Penguin History of Britain 1066–1284. London, UK: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-014824-4.

- Cathcart King, David James. (1988) The Castle in England and Wales: An Interpretative History. London, UK: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-918400-08-2.

- Colvin, Howard M. (1986) “Royal Gardens in Medieval England,” in MacDougal, Elisabeth B. (ed) (1986) Medieval Gardens. Washington, US: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-88402-146-9.

- Crouch, David. (1982) “Geoffrey de Clinton and Roger, Earl of Warwick: New Men and Magnates in the Reign of Henry I,” in Historical Research, 55 (1982).

- Doherty, P.C. (2003) Isabella and the Strange Death of Edward II. London, UK: Robinson. ISBN 1-84119-843-9.

- Emery, Anthony. (2000) Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: East Anglia, Central England and Wales, Volume II. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58131-8.

- Emery, Anthony. (2006) Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: Southern England. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58132-5.

- Greene, Kevin and Tom Moore. (2010) Archaeology: An Introduction. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-49639-1.

- Hackett, Helen. (2009) Shakespeare and Elizabeth: the Meeting of Two Myths. Princeton, US: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12806-1.

- Hall, Hubert. (2003) Society in the Elizabethan Age. Whitefish, US: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7661-3974-9.

- Haynes, Alan. (1987) The White Bear: The Elizabethan Earl of Leicester. London, UK: Peter Owen. ISBN 0-7206-0672-1.

- Hughes, Ann. (2002) Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, 1620–1660. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52015-7.

- Hull, Lise E. (2006) Britain’s Medieval Castles. Westport, US: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-98414-4.

- Hull, Lise E. and Whitehorne, Stephen. (2008) Great Castles of Britain and Ireland. London, UK: New Holland Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84773-130-2.

- Hull, Lise E. (2009) Understanding the Castle Ruins of England and Wales: How to Interpret the History and Meaning of Masonry and Earthworks. Jefferson, US: MacFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3457-2.

- Johnson, Matthew. (2000) “Self-Made Men and the Staging of Agency,” in Dobres, Marcia-Anne and John E. Robb. (eds) (2000) Agency in Archaeology. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-20760-7.

- Johnson, Matthew. (2002) Behind the Castle Gate: From Medieval to Renaissance. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-25887-6.

- Morris, Richard K. (2007) “A Plan for Kenilworth Castle at Longleat,” English Heritage Historical Review, 2 (2007).

- Morris, Richard K. (2010) Kenilworth Castle. (Second edition) London, UK: English Heritage. ISBN 978-1-84802-075-7.

- Mortimer, Ian. (2006) The Perfect King: The Life of Edward III, Father of the English Nation. London, UK: Vintage Press. ISBN 978-0-09-952709-1.

- Pettifer, Adrian. (1995) English Castles: A Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-782-5.

- Platt, Colin. (1994) Medieval England: A Social History and Archaeology from the Conquest to 1600 AD. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41512-913-8.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville. (1990) The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political history. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3.

- Prestwich, Michael. (1988) Edward I. Berkeley, US and Los Angeles, US: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06266-5.

- Roberts, Keith and John Tincey. (2001) Edgehill 1642: First Battle of the English Civil War. Botley, UK: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-85532-991-1.

- Sharpe, Henry. (1825) Concise History and Description of Kenilworth Castle: From its Foundation to the Present Time, 16th edition. Warwick: Sharpe. OCLC 54148330.

- Shaw, Harry E. (1983) The Forms of Historical Fiction: Sir Walter Scott and his Successors. New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-1592-0.

- Singman, Jeffrey L. (1995) Daily life in Elizabethan England. Westport, US: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-29335-1.

- Smith, Bill. (2005) Armstrong Siddeley Motors: The Cars, the Company and the People in Definitive Detail. Dorchester, UK: Veloce Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904788-36-2.

- Stokstad, Marilyn. (2005) Medieval Castles. Westport, US: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-32525-0.

- Thompson, M. W. (1965) “Two levels of the mere at Kenilworth Castle, Warwickshire,” in The Society of Medieval Archaeology Journal, 9 (1965).

- Thompson, M. W. (1977) “Three Stages in the Construction of the Hall at Kenilworth Castle,” in Apted, M. R., R. Gilyard-Beer and A. D. Saunders. (eds) (1977) Ancient Monuments and their Interpretation: Essays Presented to A. J. Taylor. Chichester, UK: Phillimore. ISBN 978-0-85033-239-1.

- Thompson, M. W. (1991) The Rise of the Castle. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-08853-4.

- Walsingham, Thomas, David Preest and James Clark. (2005) The Chronica Maiora of Thomas Walsingham, 1376–1422. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-144-0.

- Weir, Alison. (2006) Queen Isabella: She-Wolf of France, Queen of England. London, UK: Pimlico Books. ISBN 978-0-7126-4194-4.

- Westby-Gibson, John. (1887) “Chaloner, Thomas (1561-1615),” in Stephen, Leslie. (ed) (1887) The Dictionary of National Biography : From the Earliest Times to 1900: Volume 9, Canute – Chaloner. London, UK: Smith, Elder and Co. OCLC 163195750.

Attribution

The text of this page was adapted from “Kenilworth Castle” on the English language website Wikipedia, as the version dated 2 November 2018, and accordingly the text of this page is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Principal editors have included Hchc2009 and Nev1, and the contributions of all editors can be found on the history tab of the Wikipedia article.

Photographs on this page include those drawn from the Wikimedia, the Yale Centre for British Art, and Flickr websites, as of 2 November 2018, and attributed and licensed as follows: “Going Home“, author Steve Kinnersley, released under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0; “Kenilworth Castle keep, 2008“, author Dave, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Kenilworth Castle, 2008“, author Dave, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Kenilworth castle keep and great hall“, author Robek, released under CC BY 2.5; “Reconstruction of the castle around the time of Elizabeth I’s visit” (Crown Copyright, expired); “Kenilworth fireplace“, author miteyheroes, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Kenilworth Castle window in Leicester’s gatehouse“, author Phil W Shirley, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Kenilworth Castle – Hollar” (Public Domain); “The castle depicted by James Ward in 1840” (Public Domain); “Kenilworth Castle – Great Hall“, author Damek (Adam Pontiek), released under CC BY 2.0; “14042814_Kenilworth Castle“, author David, released under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0; “Kenilworth Castle“, author helen@littlethorpe, released under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0; “KenilworthCastleGardens1” (Public Domain); “Kenilworth castle“, author PaulJohnson, released under CC BY-SA 3.0.