15th century

Decline of English castles

By the 15th century very few castles were well maintained by their owners. Many royal castles were receiving insufficient investment to allow them to be maintained – roofs leaked, stone work crumbled, lead or wood was stolen. The Crown was increasingly selective about which royal castles it maintained, with others left to decay. By the 15th century only Windsor, Leeds, Rockingham and Moor End were kept up as comfortable accommodation; Nottingham and York formed the backbone for royal authority in the north, and Chester, Gloucester and Bristol forming the equivalents in the west. Even major fortifications such as the castles of North Wales and the border castles of Carlisle, Bamburgh and Newcastle upon Tyne saw funding and maintenance reduced. Many royal castles continued to have a role as the county gaol, with the gatehouse frequently being used as the principal facility.

The ranks of the baronage continued to reduce in the 15th century, producing a smaller elite of wealthier lords but reducing the comparative wealth of the majority. and many baronial castles fell into similar decline. John Leland’s 16th-century accounts of English castles are replete with descriptions of castles being “sore decayed”, their defences “in ruine” or, where the walls might still be in good repair, the “logginges within” were “decayed”. English castles did not play a decisive role during the Wars of the Roses, fought between 1455 and 1485, which were primarily in the form of pitched battles between the rival factions of the Lancastrians and the Yorkists.

Renaissance palaces

The 15th and 16th centuries saw a small number of British castles develop into still grander structures, often drawing on the Renaissance views on architecture that were increasing in popularity on the continent. Tower keeps, large solid keeps used for private accommodation, probably inspired by those in France had started to appear in the 14th century at Dudley and Warkworth. In the 15th century the fashion spread with the creation of very expensive, French-influenced palatial castles featuring complex tower keeps at Wardour, Tattershall and Raglan Castle. In central and eastern England castles began to be built in brick, with Caister, Kirby Muxloe and Tattershall forming examples of this new style. North of the border the construction of Holyrood Great Tower between 1528 and 1532 picked up on this English tradition, but incorporated additional French influences to produce a highly secure but comfortable castle, guarded by a gun park.

Royal builders in Scotland led the way in adopting further European Renaissance styles in castle design. James IV and James V used exceptional one-off revenues, such as the forfeiture of key lands, to establish their power across their kingdom in various ways including constructing grander castles such as Linlithgow, almost invariably by extending and modifying existing fortifications. These Scottish castle palaces drew on Italian Renaissance designs, in particular the fashionable design of a quadrangular court with stair-turrets on each corner, using harling to giving them a clean, Italian appearance. Later the castles drew on Renaissance designs in France, such as the work at Falkland and Stirling Castle. The shift in architectural focus reflected changing political alliances, as James V had formed a close alliance with France during his reign. In the words of architectural historian John Dunbar the results were the “earliest examples of coherent Renaissance design in Britain”.

These changes also included shifts in social and cultural beliefs. The period saw the disintegration of the older feudal order, the destruction of the monasteries and widespread economic changes, altering the links between castles and the surrounding estates.

Within castles, the Renaissance saw the introduction of the idea of public and private spaces, placing new value on castles having private spaces for the lord or his guests away from public view. Although the elite in Britain and Ireland continued to maintain and build castles in the style of the late medieval period there was a growing understanding through the Renaissance, absent in the 14th century, that domestic castles were fundamentally different from the military fortifications being built to deal with the spread of gunpowder artillery. Castles continued to be built and reworked in what cultural historian Matthew Johnson has described as a “conscious attempt to invoke values seen as being under threat”. The results, as seen at Kenilworth Castle for example, could include huge castles deliberately redesigned to appear old and sporting chivalric features, but complete with private chambers, Italian loggias and modern luxury accommodation.

Although the size of noble households shrank slightly during the 16th century, the number of guests at the largest castle events continued to grow. 2,000 came to a feast at Cawood Castle in 1466, while the Duke of Buckingham routinely entertained up to 519 people at Thornbury Castle at the start of the 16th century. When Elizabeth I visited Kenilworth in 1575 she brought an entourage of 31 barons and 400 staff for a visit that lasted an exceptional 19 days; Leicester, the castle’s owner, entertained the Queen and much of the neighbouring region with pageants, fireworks, bear baiting, mystery plays, hunting and lavish banquets. With this scale of living and entertainment the need to find more space in older castles became a major issue in both England and Scotland.

Tower houses

Tower houses were a common feature of British and Irish castle building in the late medieval period: over 3,000 were constructed in Ireland, around 800 in Scotland and over 250 in England. A tower house would typically be a tall, square, stone-built, crenelated building; Scottish and Ulster tower houses were often also surrounded by a barmkyn or bawn, a walled courtyard designed to hold valuable animals securely, but not necessarily intended for serious defence. Many of the gateways in these buildings were guarded with yetts, grill-like doors made out of metal bars. Smaller versions of tower houses in northern England and southern Scotland were known as Peel towers, or pele houses, and were built along both sides of the border regions. In Scotland a number were built in Scottish towns. It was originally argued that Irish tower houses were based on the Scottish design, but the pattern of development of such castles in Ireland does not support this hypothesis.

The defences of tower houses were primarily aimed to provide protection against smaller raiding parties and were not intended to put up significant opposition to an organised military assault, leading historian Stuart Reid to characterise them as “defensible rather than defensive”. Gunports for heavier guns were built into some Scottish tower houses by the 16th century but it was more common to use lighter gunpowder weapons, such as muskets, to defend Scottish tower houses. Unlike Scotland, Irish tower houses were only defended with relatively light handguns and frequently reused older arrowloops, rather than more modern designs, to save money.

Analysis of the construction of tower houses has focused on two key driving forces. The first is that the construction of these castles appears to have been linked to periods of instability and insecurity in the areas concerned. In Scotland James IV’s forfeiture of the Lordship of the Isles in 1494 led to an immediate burst of castle building across the region and, over the longer term, an increased degree of clan warfare, while the subsequent wars with England in the 1540s added to the level of insecurity over the rest of the century. Irish tower houses were built from the end of the 14th century onward as the countryside disintegrated into the unstable control of a large number of small lordships and Henry VI promoted their construction with financial rewards in a bid to improve security. English tower houses were built along the frontier with Scotland in a dangerous and insecure period.

Secondly, and paradoxically, appears to have been the periods of relative prosperity. Contemporary historian William Camden observed of the northern English and the Scots, “there is not a man amongst them of a better sort that hath not his little tower or pile”, and many tower houses seem to have been built as much as status symbols as defensive structures. Along the English-Scottish borders the construction pattern follows the relative prosperity of the different side: the English lords built tower houses primarily in the early 15th century, when northern England was particularly prosperous, while their Scottish equivalents built them in late 15th and early 16th centuries, boom periods in the economy of Scotland. In Ireland the growth of tower houses during the 15th century mirrors the rise of cattle herding and the resulting wealth that this brought to many of the lesser lords in Ireland.

Further development of gunpowder artillery

Cannons continued to be improved during the 15th and 16th centuries. Castle loopholes were adapted to allow cannons and other firearms to be used in a defensive role, but offensively gunpowder weapons still remained relatively unreliable. England had lagged behind Europe in adapting to this new form of warfare; Dartmouth and Kingswear Castles, built in the 1490s to defend the River Dart, and Bayard’s Cove, designed in 1510 to defend Dartmouth harbour itself, were amongst the few English castles designed in the continental style during the period, and even these lagged behind the cutting edge of European design. Scottish castles were more advanced in this regard, partially as a result of the stronger French architectural influences. Ravenscraig Castle in Scotland, for example, was an early attempt in the 1460s to deploy a combination of “letter box” gun-ports and low-curved stone towers for artillery weapons. These letter box gun-ports, common in mainland Europe, rapidly spread across Scotland but were rarely used in England during the 15th century. Scotland also led the way in adopting the new caponier design for castle ditches, as constructed at Craignethan Castle.

Henry VIII became concerned with the threat of French invasion during 1539 and was familiar with the more modern continental designs. He responded to the threat by building a famous sequence of forts, called the Device Forts, or Henrician Castles, along the south coast of England specifically designed to be equipped with, and to defend against, gunpowder artillery. These forts still lacked some of the more modern continental features, such as angled bastions. Each fort had a slightly different design, but as a group they shared common features, with the fortification formed around a number of compact lobes, often in a quatrefoil or trefoil shape, designed to give the guns a 360 degree angle of fire. The forts were usually tiered to allow the guns to fire over one another and had features such as vents to disperse the gunpowder smoke. It is probable that many of the forts were also originally protected by earth bulwarks, although these have not survived. The resulting forts have been described by historian Christopher Duffy as having “an air at once sturdy and festive, rather like a squashed wedding cake”.

These coastal defences marked a shift away from castles, which were both military fortifications and domestic buildings, towards forts, which were garrisoned but not domestic; often the 1540s are chosen as a transition date for the study of castles as a consequence. The subsequent years also marked almost the end of indigenous English fortification design – by the 1580s, English castle improvements were almost entirely dominated by imported European experts. The superiority of Scottish castle design also diminished; the Half Moon battery built at Edinburgh Castle in 1574, for example, was already badly dated in continental terms by the time it was built. The limited number of modern fortifications built in Ireland, such as those with the first gunports retrofitted to Carrickfergus Castle in the 1560s and at Corkbeg in Cork Harbour and built in the 1570s in fear of an invasion, were equally unexceptional by European standards.

Nonetheless, improved gunpowder artillery played a part in the reconquest of Ireland in the 1530s, where the successful English siege of Maynooth Castle in 1530 demonstrated the power of the new siege guns. There were still relatively few guns in Ireland however and, during the Nine Years’ War at the end of the century, the Irish were proved relatively unskilled in siege warfare with artillery used mainly by the English.

In both Ireland and Scotland the challenge was how to transport artillery pieces to castle sieges; the poor state of Scottish roads required expensive trains of pack horses, which only the king could afford, and in Ireland the river network had to be frequently used to transport the weapons inland. In these circumstances older castles could frequently remain viable defensive features, although the siege of Cahir Castle in 1599 and the attack on Dunyvaig Castle on Islay in 1614 proved that if artillery could be brought to bear, previously impregnable castle walls might fall relatively quickly.

17th century

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

In 1603 James VI of Scotland inherited the crown of England, bringing a period of peace between the two countries. The royal court left for London and, as a result – with the exceptions of occasional visits, building work on royal castles north of the border largely ceased. Investment in English castles, especially royal castles, declined dramatically. James sold off many royal castles in England to property developers, including York and Southampton Castle. A royal inspection in 1609 highlighted that the Edwardian castles of North Wales, including Conwy, Beaumaris and Caernarfon were “[u]tterlie decayed”.; a subsequent inspection of various English counties in 1635 found a similar picture: Lincoln, Kendal, York, Nottingham, Bristol, Queenborough, Southampton and Rochester were amongst those in a state of dilapidation. In 1642, a pamphlet described many English castles as “muche decayed” and as requiring “much provision” for “warlike defence”.

Those maintained as private homes; such as Arundel, Berkeley, Carlisle and Winchester were in much better condition, but not necessarily defendable in a conflict; while some such as Bolsover were redesigned as more modern dwellings in a Palladian style. A handful of coastal forts and castles, amongst them Dover Castle, remained in good military condition with adequate defences.

In 1642 the English Civil War broke out, initially between supporters of Parliament and the Royalist supporters of Charles I. The war expanded to include Ireland and Scotland, and dragged on into three separate conflicts in England itself. The war was the first prolonged conflict in Britain to involve the use of artillery and gunpowder. English castles were used for various purposes during the conflict. York Castle formed a key part of the city defences, with a military governor; rural castles such as Goodrich could be used a bases for raiding and for control of the surrounding countryside; larger castles, such as Windsor, became used for holding prisoners of war or as military headquarters.

During the war, castles were frequently brought back into fresh use: existing defences would be renovated, while walls would be “countermured”, or backed by earth, in order to protect from cannons. Towers and keeps were filled with earth to make gun platforms, such as at Carlisle and Oxford Castle. New earth bastions could be added to existing designs, such as at Cambridge and Carew Castle and at the otherwise unfortified Basing House the surrounding Norman ringwork was brought back into commission.The costs could be considerable, with the work at Skipton Castle coming to over £1000.

Sieges became a prominent part of the war with over 300 occurring during the period, many of them involving castles. Indeed, as Robert Liddiard suggests, the “military role of some castles in the seventeenth century is out of all proportion to their medieval histories”. Artillery formed an essential part of these sieges, with the “characteristic military action” according to military historian Stephen Bull, being “an attack on a fortified strongpoint” supported by artillery. The ratio of artillery pieces to defenders varied considerably in sieges, but in all cases there were more guns than in previous conflicts; up to one artillery piece for every nine defenders was not unknown in extreme cases, such as near Pendennis Castle. The growth in the number and size of siege artillery favoured those who had the resources to purchase and deploy these weapons.

Artillery had improved by the 1640s but was still not always decisive, as the lighter cannon of the period found it hard to penetrate earth and timber bulwarks and defences – demonstrated in the siege of Corfe. Mortars, able to lob fire over the taller walls, proved particularly effective against castles – in particular those more compact ones with smaller courtyards and open areas, such as at Stirling Castle.

The heavy artillery introduced in England eventually spread to the rest of the British Isles. Although up to a thousand Irish soldiers who had served in Europe returned during the war, bringing with them experience of siege warfare from the Thirty Years’ War in Europe, it was the arrival of Oliver Cromwell’s train of siege guns in 1649 that transformed the conflict, and the fate of local castles. None of the Irish castles could withstand these Parliamentary weapons and most quickly surrendered. In 1650, Cromwell invaded Scotland and again his heavily artillery proved decisive.

The Restoration

The English Civil War resulted in Parliament issuing orders to slight or damage many castles, particularly in prominent royal regions. This was particularly in the period of 1646 to 1651, with a peak in 1647. Around 150 fortifications were slighted in this period, including 38 town walls and a great many castles. Slighting was expensive and took some considerable effort to carry out, so damage was usually done in the most cost-effective fashion with only selected walls being destroyed. In some cases the damage was almost total, such as Pontefract Castle which had been involved in three major sieges and in this case at the request of the townsfolk who wished to avoid further conflict.

By the time that Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, the major palace-fortresses in England that had survived slighting were typically in a poor state. As historian Simon Thurley has described, the shifting “functional requirements, patterns of movement, modes of transport, aesthetic taste and standards of comfort” amongst royal circles were also changing the qualities being sought in a successful castle. Palladian architecture was growing in popularity, which sat awkwardly with the typical design of a medieval castle. Furthermore, the fashionable French court etiquette at the time required a substantial number of enfiladed rooms, in order to satisfy court protocol, and it was impractical to fit these rooms into many older buildings. A shortage of funds curtailed Charles II’s attempts to remodel his remaining castles and the redesign of Windsor was the only one to be fully completed in the Restoration years.

Many castles still retained a defensive role. Castles in England, such as Chepstow and York Castle, were repaired and garrisoned by the King. As military technologies progressed the costs of upgrading older castles could be prohibitive – the estimated £30,000 required for the potential conversion of York in 1682, gives a scale of the potential costs. Castles played a minimal role in the Glorious Revolution of 1688, although some fortifications such as Dover Castle were attacked by mobs unhappy with the religious beliefs of their Catholic governors, and the sieges of King John’s Castle in Limerick formed part of the endgame to the war in Ireland.

In the north of Britain security problems persisted in Scotland. Cromwellian forces had built a number of new modern forts and barracks, but the royal castles of Edinburgh, Dumbarton and Stirling, along with Dunstaffnage, Dunollie and Ruthven Castle, also continued in use as practical fortifications. Tower houses were being built until the 1640s; after the Restoration the fortified tower house fell out of fashion, but the weak state of the Scottish economy was such that while many larger properties were simply abandoned, the more modest castles continued to be used and adapted as houses, rather than rebuilt. In Ireland tower houses and castles remained in use until after the Glorious Revolution, when events led to a dramatic shift in land ownership and a boom in the building of Palladian country houses; in many cases using timbers stripped from the older, abandoned generation of castles and tower houses.

Bilbliography

Attribution

The text of this page was adapted from “Castles in Great Britain and Ireland” on the English language website Wikipedia, as the version dated 22 July 2018, and accordingly this page is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Principle editors have included Hchc2009, Cameron and Nev1, and the contributions of all editors can be found on the history tab of the Wikipedia article.

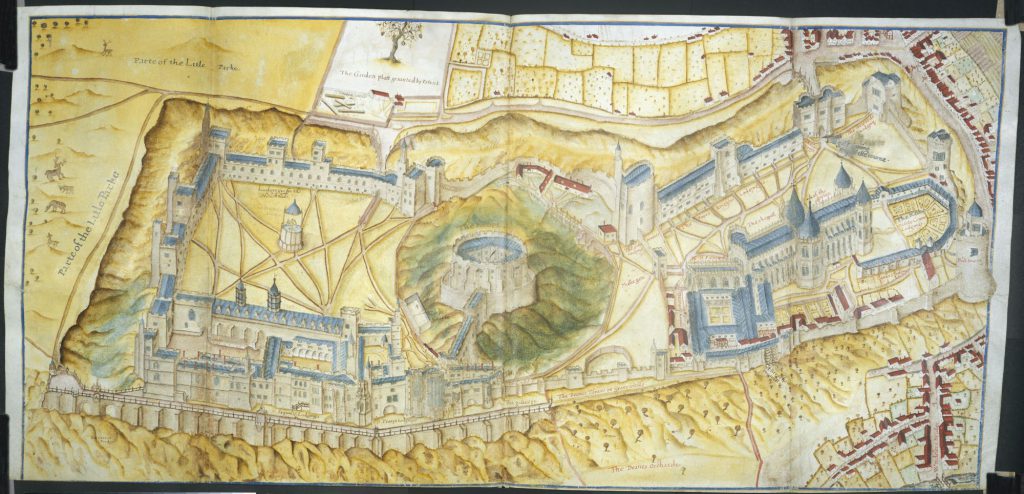

Photographs on this page include those drawn from the Wikimedia, British Library and The Metropolitan Museum of Art websites, as of 24 May 2020, and attributed and licensed as follows: “RidsdalePanorma” (Public Domain); “Birdseye view of Windsor Castle: shelfmark Harley MS 3749, f.3“, photograph copyright British Library, released under CC BY-NC 4.0; “IMG ClononyCastle5782w” (Public Domain); “Ravenscraig Castle“, author Kilnburn, released for any purpose, subject to attribution; “St Mawes Castle, Cornwall, England“, author Ulli1105, released under CC BY-SA 3.0; adapted from “Bolsover Castle 17th century“, author Andrew Michaels, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Roaring Meg mortar.JPG“, author Hchc2009, released under CC BY-SA 3.0; “Corfe Castke 57“, author Chin tin tin, released under CC BY-SA 3.0; “Two ladies in a landscape with a castle” (Public Domain).