18th century

Military and governmental use

Some castles continued to have modest military utility into the 18th century. Until 1745 a sequence of Jacobite risings threatened the Crown in Scotland, culminating in the rebellion in 1745. Various royal castles were maintained during the period either as part of the English border defences, like Carlisle, or forming part of the internal security measures in Scotland itself, like Stirling Castle. Stirling was able to withstand the Jacobite attack in 1745, although Carlisle was taken; the siege of Blair Castle, at the end of the rebellion in 1746, was the final castle siege to occur in the British Isles. In the aftermath of the conflict Corgaff and many others castles were used as barracks for the forces sent to garrison the Highlands. Some castles, such as Portchester, were used for holding prisoners of war during the Napoleonic Wars at the end of the century and were re-equipped in case of a popular uprising during this revolutionary period. In Ireland, Dublin Castle was rebuilt following a fire and reaffirmed as the centre of British administrative and military power.

Many castles remained in use as county gaols, run by gaolers as effectively private businesses; frequently this involved the gatehouse being maintained as the main prison building, as at Cambridge, Bridgnorth, Lancaster, Newcastle and St Briavels. During the 1770s, the prison reformer John Howard conducted his famous survey of prisons and gaols, culminating in his 1777 work The State of the Prisons. This documented the poor quality of these castle facilities; prisoners in Norwich Castle lived in a dungeon, with the floor frequently covered by an inch of water; Oxford was “close and offensive”; Worcester was so subject to gaol-fever that the castle surgeon would not enter the prison; Gloucester was “wretched in the extreme”. Howard’s work caused a shift in public opinion against the use of these older castle facilities as gaols.

Social and cultural use

By the middle of the century medieval ruined castles had become fashionable once again. They were considered an interesting counterpoint to the now conventional Palladian classical architecture, and a way of giving a degree of medieval allure to their new owners. Historian Oliver Creighton suggests that the ideal image of a castle by the 1750s included “broken, soft silhouettes and [a] decayed, rough appearance”. In some cases the countryside surrounding existing castles was remodelled to highlight the ruins, as at Henderskelfe Castle, or at “Capability” Brown’s reworking of Wardour Castle. Alternatively, ruins might be repaired and reinforced to present a more suitable appearance, as at Harewood Castle. In other cases mottes, such as that at Groby Castle, were reused as the bases for dramatic follies, or alternatively entirely new castle follies could be created; either from scratch or by reusing original stonework, as occurred during the building of Conygar Tower for which various parts of Dunster Castle were cannibalised.

Castles were also becoming tourist attractions for the first time. By the 1740s Windsor Castle had become an early tourist attraction; wealthier visitors who could afford to pay the castle keeper could enter, see curiosities such as the castle’s narwhal horn and, by the 1750s, buy the first guidebooks. The first guidebook to Kenilworth Castle followed in 1777 with many later editions following in the coming decades. By the 1780s and 1790s, visitors were beginning to progress as far as Chepstow, where an attractive female guide escorted tourists around the ruins as part of the popular Wye Tour. In Scotland, Blair Castle became a popular attraction on account of its landscaped gardens, as did Stirling Castle with its romantic connections. Caernarfon in North Wales appealed to many visitors, especially artists. Irish castles proved less popular, partially because contemporary tourists regarded the country as being somewhat backward, and the ruins therefore failed to provide the necessary romantic contrast with modern life.

The appreciation of castles developed as the century progressed. During the 1770s and 1780s, the concept of the picturesque ruin was popularised by the English clergyman William Gilpin. Gilpin published several works on his journeys through Britain, expounding the concept of the “correctly picturesque” landscape. Such a landscape, Gilpin argued, usually required a building such as a castle or other ruin to add “consequence” to the natural picture. Paintings in this style usually portrayed castles as indistinct, faintly coloured objects in the distance; in writing, the picturesque account eschewed detail in favour of bold first impressions on the sense. The ruins of Goodrich particularly appealed to Gilpin and his followers; Conwy was, however, too well preserved and uninteresting. By contrast the artistic work of antiquarians James Bentham and James Essex at the end of the century, while stopping short of being genuine archaeology, was detailed and precise enough to provide a substantial base of architectural fine detail on medieval castle features and enabled the work of architects such as Wyatt.

19th century

Military and governmental use

The military utility of the remaining castles in Britain and Ireland continued to diminish. Some castles became regimental depots, including Carlisle Castle and Chester Castle. Carrickfergus Castle was re-equipped with gunports in order to provide coastal defences at the end of the Napoleonic period. Political instability was a major issue during the early 19th century and the popularity of the Chartist movement led to proposals to refortify the Tower of London in the event of civil unrest. In Ireland, Dublin Castle played an increasing role in Ireland as Fenian pressures for independence grew during the century.

The operation of local prisons in locations such as castles had been criticised, since John Howard’s work in the 1770s, and pressure for reform continued to grow in the 1850s and 1860s. Reform of the legislation surrounding bankruptcy and debt in 1869 largely removed the threat of imprisonment for unpaid debts, and in the process eliminated the purpose of the debtor’s prisons in castles such as St Briavels.

Efforts were made to regularise conditions in local prisons but without much success, and these failures led to prison reform in 1877 which nationalised British prisons, including prisons at castles like York. Compensation was paid to the former owners, although in cases such as York where the facilities were considered so poor as to require complete reconstruction, this payment was denied. In the short term this led to a 39 percent reduction in the number of prisons in England, including some famous castle prisons such as Norwich; over the coming years, centralisation and changes in prison design led to the closure of most remaining castle prisons.

Social and cultural use

Many castles saw increased visitors by tourists, helped by better transport links and the growth of the railways. The armouries at the Tower of London opened for tourists in 1828 with 40,000 visitors in their first year; by 1858 the numbers had grown to over 100,000 a year. Attractions such as Warwick Castle received 6,000 visitors during 1825 to 1826, many of them travelling from the growing industrial towns in the nearby Midlands, while Victorian tourists recorded being charged six-pence to wander around the ruins of Goodrich Castle. The spread of the railway system across Wales and the Marches strongly influenced the flow of tourists to the region’s castles. In Scotland tourist tours became increasingly popular during the 19th century, usually starting at Edinburgh complete with Edinburgh Castle, and then spending up to two weeks further north, taking advantage of the expanding rail and steamer network. Blair Castle remained popular, but additional castles joined the circuit – Cawdor Castle became popular once the railway line reached north to Fort William.

Purchasing and reading guidebooks became an increasingly important part of visiting castles; by the 1820s visitors could buy an early guidebook at Goodrich outlining the castle’s history, the first guidebook to the Tower of London was published in 1841 and Scottish castle guidebooks became well known for providing long historical accounts of their sites, often drawing on the plots of Romantic novels for the details. Indeed, Sir Walter Scott’s historical novels Ivanhoe and Kenilworth helped to establish the popular Victorian image of a Gothic medieval castle. Scott’s novels set in Scotland also popularised several northern castles, including Tantallon which was featured in Marmion. Histories of Ireland began to stress the role of castles in the rise of Protestantism and “British values” in Ireland, although tourism remained limited.

One response to this popularity was in commissioning the construction of replica castles. These were particularly popular at beginning of the 19th century, and again later in the Victorian period. Design manuals were published offering details of how to recreate the appearance of an original Gothic castles in a new build, leading to a flurry of work, such as Eastnor in 1815, the fake Norman castle of Penrhyn between 1827 and 1837 and the imitation Edwardian castle of Goodrich Court in 1828. The later Victorians built the Welsh Castell Coch in the 1880s as a fantasy Gothic construction and the last such replica, Castle Drogo, was built as late as 1911.

Another response was to improve existing castles, bringing their often chaotic historic features into line with a more integrated architectural aesthetic in a style often termed Gothic Revivalism. There were numerous attempts to restore or rebuild castles so as to produce a consistently Gothic style, informed by genuine medieval details, a movement in which the architect Anthony Salvin was particularly prominent – as illustrated by his reworking of Alnwick and much of Windsor Castle. A similar trend can be seen at Rothesay where William Burges renovated the older castle to produce a more “authentic” design, heavily influenced by the work of the French architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc.

North of the border, this resulted in the distinctive style of Scots Baronial Style architecture, which took French and traditional medieval Scottish features and reinvented them in a baroque style. The style also proved popular in Ireland with George Jones’ Oliver Castle in the 1850s, for example, forming a good example of the fashion. As with Gothic Revivalism, Scots Baronial architects frequently “improved” existing castles: Floors Castle was transformed in 1838 by William Playfair who added grand turrets and cupolas. In a similar way the 16th-century tower house of Lauriston Castle was turned into the Victorian ideal of a “rambling medieval house”. The style spread south and the famous architect Edward Blore added a Scots Baronial touch to his work at Windsor.

With this pace of change concerns had begun to grow by the middle of the century about the threat to medieval buildings in Britain, and in 1877 William Morris established the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildi One result of public pressure was the passing of the Ancient Monuments Protection Act 1882, but the provisions of the act focused on unoccupied prehistoric structures and medieval buildings such as castles were exempted from it leaving no legal protection.

20th–21st century

1900–1945

During the first half of the century several castles were maintained, or brought back into military use. During the Irish War of Independence Dublin Castle remained the centre of the British administration, military and intelligence operations in Ireland until the transfer of power and the castle to the Irish Free State in 1922. During the Second World War, the Tower of London was used to hold and execute suspected spies, and was used to briefly detain Rudolf Hess, Adolf Hitler’s deputy, in 1941. Edinburgh Castle was used as a prisoner of war facility, while Windsor Castle was stripped of more delicate royal treasures and used to guard the British royal family from the dangers of the Blitz.

Some coastal castles were used to support naval operations: Dover Castle‘s medieval fortifications used as basis for defences across the Dover Strait; Pitreavie Castle in Scotland was used to support the Royal Navy; and Carrickfergus Castle in Ireland was used as a coastal defence base. Some castles, such as Cambridge and Pevensey, were brought into local defence plans in case of a German invasion. A handful of these castles retained a military role after the war; Dover was used as a nuclear war command centre into the 1950s, while Pitreavie was used by NATO until the turn of the 21st century.

The strong cultural interest in British castles persisted in the 20th century. In some cases this had destructive consequences as wealthy collectors bought and removed architectural features and other historical artefacts from castles for their own collections, a practice that produced significant official concern. Some of the more significant cases included St Donat’s Castle, bought by William Randolph Hearst in 1925 and then decorated with numerous medieval buildings removed from their original sites around Britain, and the case of Hornby, where many parts of the castle were sold off and sent to buyers in the United States. Partially as a result of these events, increasing legal powers were introduced to protect castles – acts of parliament in 1900 and 1910 widened the terms of the earlier legislation on national monuments to allow the inclusion of castles. An act of Parliament in 1913 introduced preservation orders for the first time and these powers were extended in 1931. Similarly, after the end of the Irish Civil War, the new Irish state took early action to extend and strengthen the previous British legislation to protect Irish national monuments.

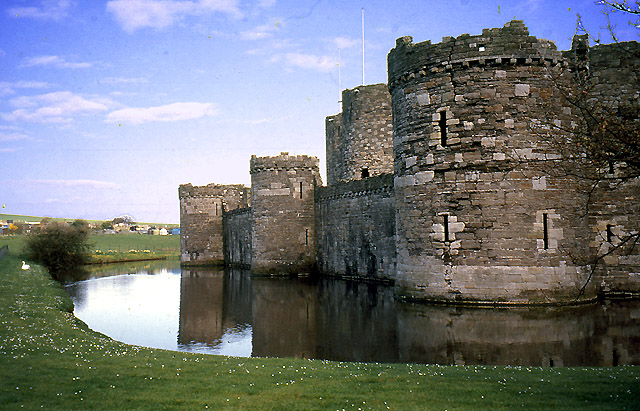

Around the beginning of the century there were a number of major restoration projects on British castles. Before the outbreak of the First World War work was undertaken at Chepstow, Bodiam, Caernarfon and Tattershal; after the end of the war various major state funded restoration projects occurred in the 1920s with Pembroke, Caerphilly and Goodrich amongst the largest of these. This work typically centred on cutting back the vegetation encroaching on castle ruins, especially ivy, and removing damaged or unstable stonework; castles such as Beaumaris saw their moats cleaned and reflooded. Some castles such as Eilean Donan in Scotland were substantially rebuilt in the inter-war years. The early UK film industry took an interest in castles as potential sets, starting with Ivanhoe filmed at Chepstow Castle in 1913 and starring US leading actor King Bag

1945–21st century

After the Second World War picturesque ruins of castles became unfashionable. The conservation preference was to restore castles so as to produce what Oliver Creighton and Robert Higham have described as a “meticulously cared for fabric, neat lawns and [a] highly regulated, visitor-friendly environment”, although the reconstruction or reproduction of the original appearance of castles was discouraged. As a result, the stonework and walls of today’s castles, used as tourist attractions, are usually in much better condition than would have been the case in the medieval period. Preserving the broader landscapes of the past also rose in importance, reflected in the decision by the UNESCO World Heritage Site programme to internationally recognise several British castles including Beaumaris, Caernarfon, Conwy, Harlech, Durham and the Tower of London as deserving of special international cultural significance in the 1980s.

The single largest group of English castles are now those owned by English Heritage, created out of the former Ministry of Works in 1983. The National Trust increasingly acquired castle properties in England in the 1950s, and is the second largest single owner, followed by the various English local authorities and finally a small number of private owners. Royal castles such as the Tower of London and Windsor are owned by the Occupied Royal Palaces Estate on behalf of the nation. Similar organisations exist in Scotland, where the National Trust for Scotland was established 1931, and in Ireland, where An Taisce was created in 1948 to working alongside the Irish Ministry of Works to maintain castles and other sites. Some new organisations have emerged in recent years to manage castles, such as the Landmark Trust and the Irish Landmark Trust, which have restored a number of castles in Britain and Ireland over the last few decades.

Castles remain highly popular attractions: in 2009 nearly 2.4 million people visited the Tower of London, 1.2 million visited Edinburgh Castle, 559,000 visited Leeds Castle and 349,000 visited Dover Castle. Ireland, which for many years had not exploited the tourist potential of its castle heritage, began to encourage more tourists in the 1960s and 1970s and Irish castles are now a core part of the Irish tourist industry. British and Irish castles are today also closely linked to the international film industry, with tourist visits to castles now often involving not simply a visit to a historic site, but also a visit to the location of a popular film.

The management and handling of Britain’s historic castles has at times been contentious. Castles in the late 20th and early 21st century are usually considered part of the heritage industry, in which historic sites and events are commercially presented as visitor attractions. Some academics, such as David Lowenthal, have critiqued the way in which these histories are constantly culturally and socially reconstructed and condemned the “commercial debasement” of sites such as the Tower of London.

The challenge of how to manage these historic properties has often required very practical decisions. At one end of the spectrum owners and architects have had to deal with the practical challenges of repairing smaller decaying castles used as private houses, such as that at Picton Castle where damp proved a considerable problem. At the other end of the scale the fire at Windsor Castle in 1992 opened up a national debate about how the burnt-out castle wing should be replaced, the degree to which modern designs should be introduced and who should pay the £37 million costs (£50.2 million in 2009 terms). At Kenilworth the speculative and commercial reconstruction of the castle gardens in an Elizabethan style led to a vigorous academic debate over the interpretation of archaeological and historical evidence. Trends in conservation have altered and, in contrast to the prevailing post-war approach to conservation, recent work at castles such as Wigmore, acquired by English Heritage in 1995, has attempted to minimise the degree of intervention to the site.

Historiography

The earliest histories of British and Irish castles were recorded, albeit in a somewhat fragmented fashion, by John Leland in the 16th century and, by the 19th century, historical analysis of castles had become popular. Victorian historians such as George Clark and John Parker concluded that British castles had been built for the purposes of military defence, but believed that their history was pre-Conquest – concluding that the mottes across the countryside had been built by either the Romans or Celts.

The study of castles by historians and archaeologists developed considerably during the 20th century. The early-20th-century historian and archaeologist Ella Armitage published a ground-breaking book in 1912, arguing convincingly that British castles were in fact a Norman introduction, while historian Alexander Thompson also published in the same year, charting the course of the military development of English castles through the Middle Ages. The Victoria County History of England began to document the country’s castles on an unprecedented scale, providing an additional resource for historical analysis.

After the Second World War the historical analysis of British castles was dominated by Arnold Taylor, R. Allen Brown and D. J. Cathcart King. These academics made use of a growing amount of archaeological evidence, as the 1940s saw an increasing number of excavations of motte and bailey castles, and the number of castle excavations as a whole went on to double during the 1960s. With an increasing number of castle sites under threat in urban areas, a public scandal in 1972 surrounding the development of the Baynard’s Castle site in London contributed to reforms and a re-prioritisation of funding for rescue archaeology. Despite this the number of castle excavations fell between 1974 and 1984, with the archaeological work focusing on conducting excavations on a greater number of small-scale, but fewer large-scale sites. The study of British castles remained primarily focused on analysing their military role, however, drawing on the evolutionary model of improvements suggested by Thompson earlier in the century.

In the 1990s a wide-reaching reassessment of the interpretation of British castles took place. A vigorous academic discussion over the history and meanings behind Bodiam Castle began a debate, which concluded that many features of castles previously seen as primarily military in nature were in fact constructed for reasons of status and political power. As historian Robert Liddiard has described it, the older paradigm of “Norman militarism” as the driving force behind the formation of Britain’s castles was replaced by a model of “peaceable power”. The next twenty years was characterised by an increasing number of major publications on castle studies, examining the social and political aspects of the fortifications, as well as their role in the historical landscape. Although not unchallenged, this “revisionist” perspective remains the dominant theme in the academic literature today.

Bilbliography

Attribution

The text of this page was adapted from “Castles in Great Britain and Ireland” on the English language website Wikipedia, as the version dated 22 July 2018, and accordingly this page is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Principle editors have included Hchc2009, Cameron and Nev1, and the contributions of all editors can be found on the history tab of the Wikipedia article.

Photographs on this page are drawn from the Wikimedia website, as of 22 July 2018, and attributed and licensed as follows: “Carlisle Castle 03“, author Neil Boothman, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Old Wardour Castle 56“, author Simon Burchell, released under CC BY-SA 3.0; “Carrickfergus Castle, reflections at sunset“, author Stewart, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Edinburgh Castle from Grass Market“, author Nev1, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Penrhyn Castle“, author Indigo Goat, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Beaumaris Castle“, author Pam Brophy, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Yard 2“, author Robin Widdison, relesed under Copyrighted Free Use; “Wigmore Castle Ruins“, author Humphrey Bolton, released under CC BY-SA 2.0.