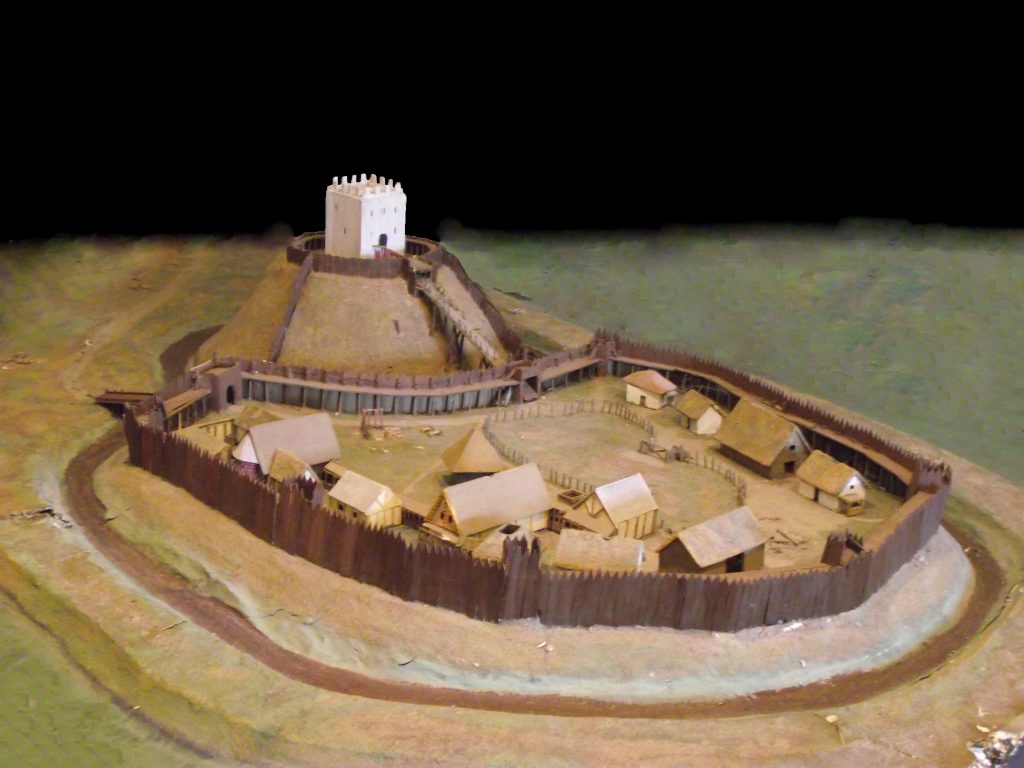

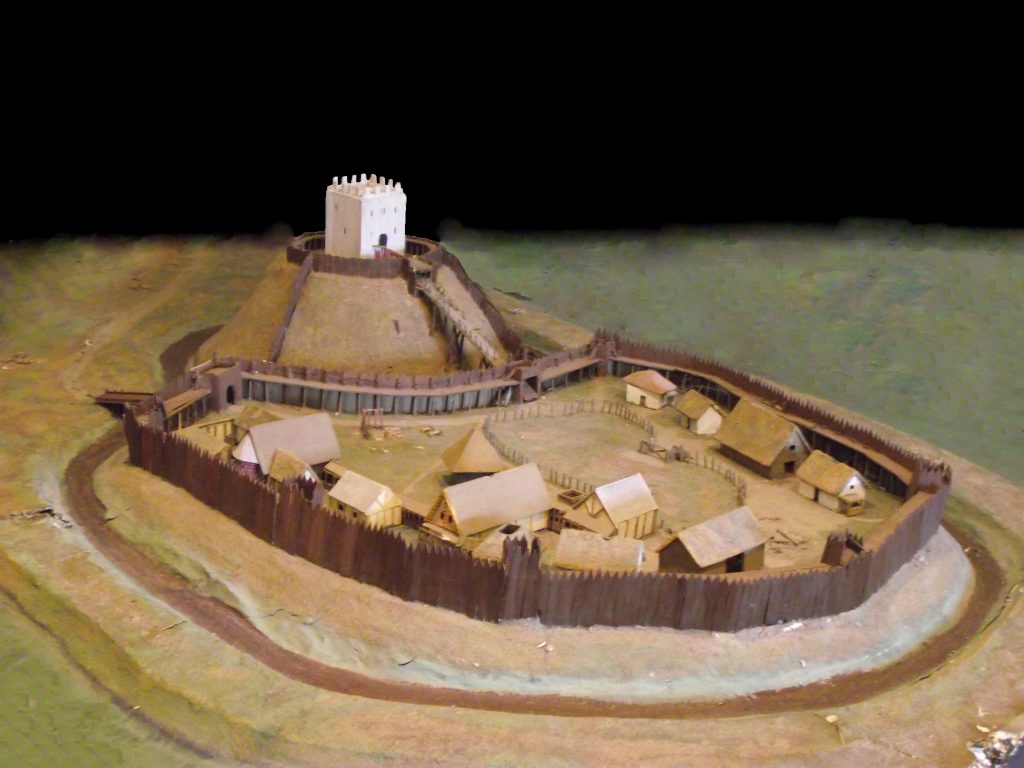

A motte-and-bailey castle is a fortification with a wooden or stone keep situated on a raised earthwork called a motte, accompanied by an enclosed courtyard, or bailey, surrounded by a protective ditch and palisade. Relatively easy to build with unskilled, often forced, labour, but still militarily formidable, these castles were built across northern Europe from the 10th century onwards. The Normans introduced the design into England and Wales following their invasion in 1066. By the end of the 13th century, the design was largely superseded by alternative forms of fortification.

Design

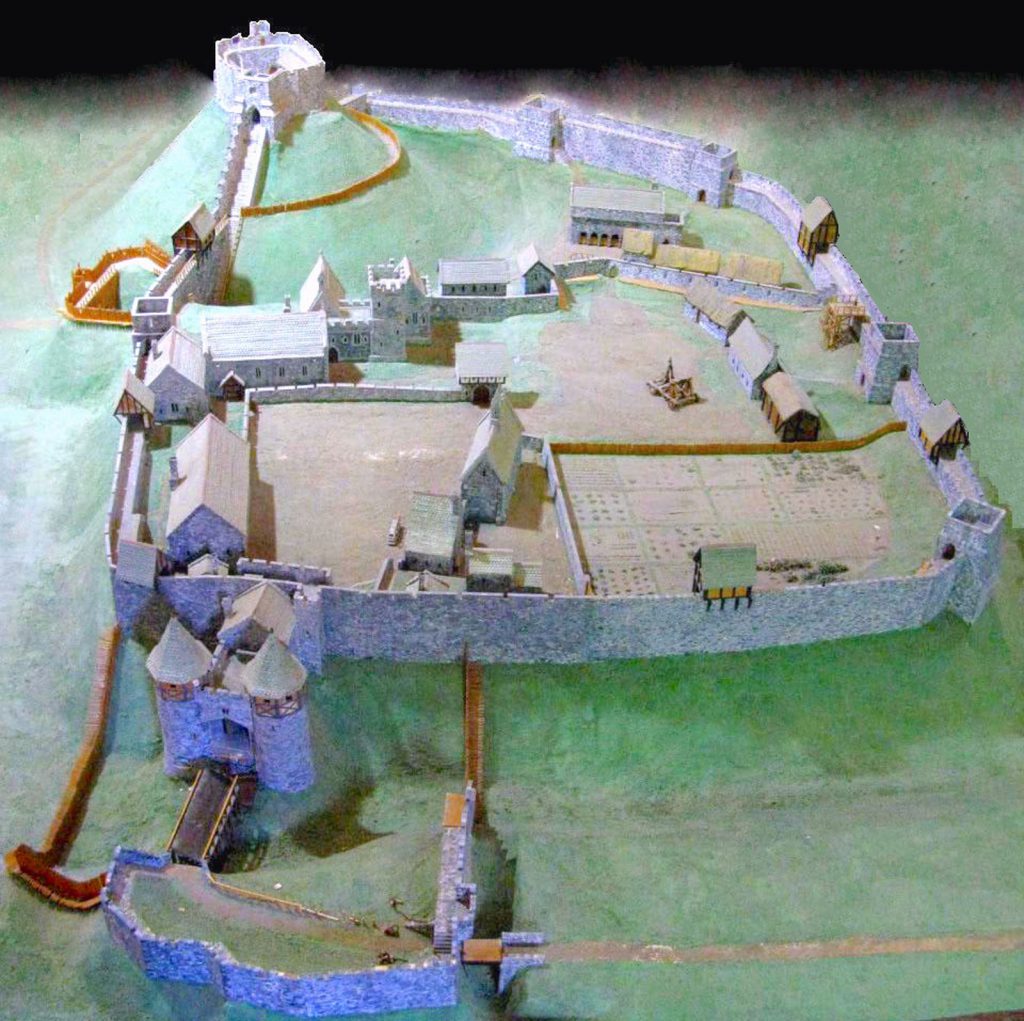

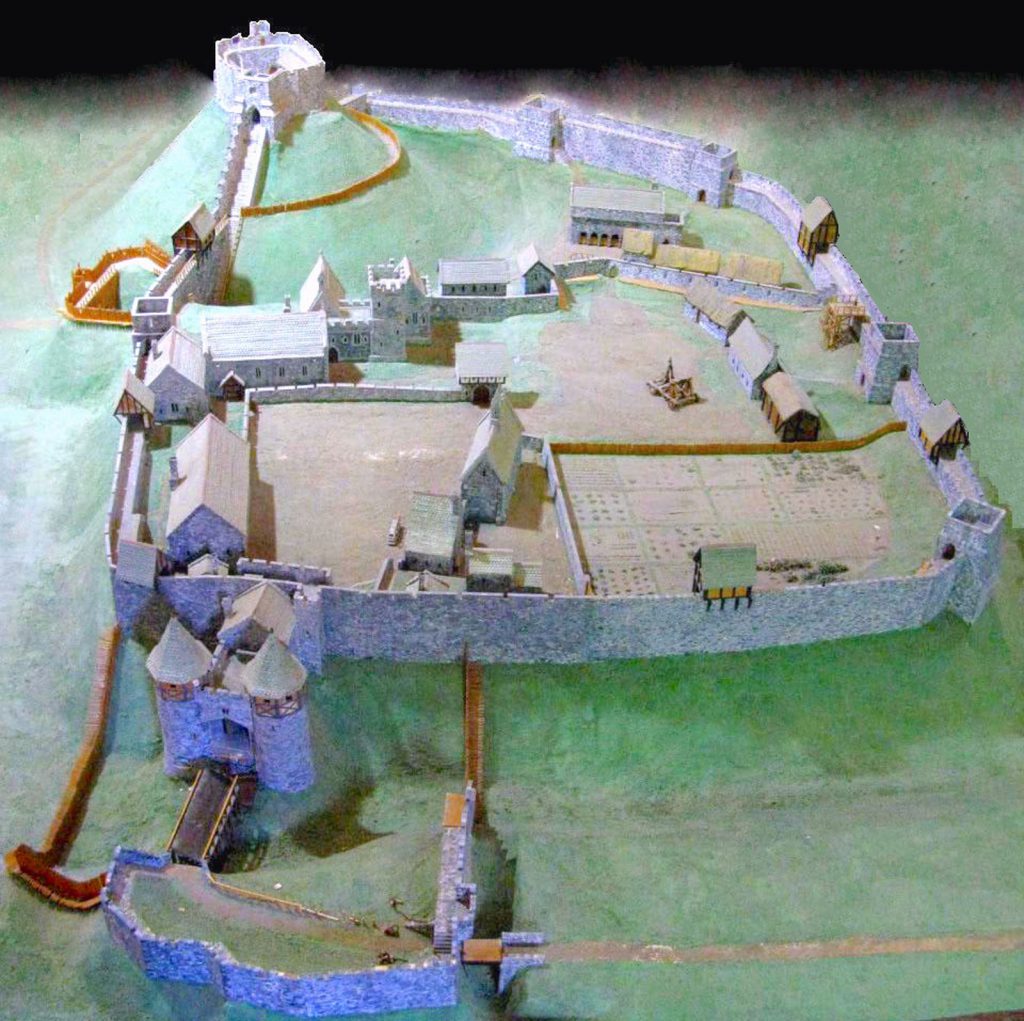

A motte-and-bailey castle was made up of two structures: a motte (a type of mound – often artificial – topped with a wooden or stone structure known as a keep); and at least one bailey (a fortified enclosure built next to the motte). The term “motte and bailey” is a relatively modern one, and is not medieval in origin. The word “motte” is the French version of the Latin mota, and in France the word motte was initially an early word for a piece of turf; it then became used to refer to a turf bank, and by the 12th century was used to refer to the castle design itself. The word “bailey” comes from the Norman-French baille, or basse-cour, referring to a low yard. In medieval sources, the Latin term castellum was used to describe the bailey complex within these castles.

One contemporary account of these structures comes from Jean de Colmieu around 1130. De Colmieu described how a motte-and-bailey castle would be built by a lord assembling:

“a mound of earth as high as they can and digging a ditch about it as wide and deep as possible. The space on top of the mound is enclosed by a palisade of very strong hewn logs, strengthened at intervals by as many towers as their means can provide. Inside the enclosure is a citadel, or keep, which commands the whole circuit of the defences. The entrance to the fortress is by means of a bridge, which, rising from the outer side of the moat and supported on posts as it ascends, reaches to the top of the mound.”

At Durham Castle, contemporaries described how the motte-and-bailey superstructure arose from the “tumulus of rising earth” with a keep rising “into thin air, strong within and without” with a “stalwart house…glittering with beauty in every part”.

The motte

Mottes were made out of earth and flattened on top, and it can be very hard to determine whether a mound is artificial or natural without excavation. Some were also built over older artificial structures, such as Bronze Age barrows. The size of mottes varied considerably, with these mounds being 3 metres to 30 metres in height (10 feet to 100 feet), and from 30 to 90 metres (98 to 295 ft) in diameter. Academics usually exclude mounds less than 3 metres (9.8 feet) high as mottes, in order to distinguish them from many other smaller mounds and platforms which often had non-military purposes.

In England and Wales, only 7 percent of mottes were taller than 10 metres (33 feet) high; 24 percent were between 10 and 5 metres (33 and 16 ft), and 69 percent were less than 5 metres (16 feet) tall. A motte was protected by a ditch around it, which would typically have also been a source of the earth and soil for constructing the mound itself.

A keep and a protective wall would usually be built on top of the motte. Some walls would be large enough to have a wall-walk around them, and the outer walls of the motte and the wall-walk could be strengthened by filling in the gap between the wooden walls with earth and stones, allowing it to carry more weight; this was called a garillum. Smaller mottes could only support simple towers with room for a few soldiers, whilst larger mottes could be equipped with a much grander building. Many wooden keeps were designed with bretèches, small balconies that projected from the upper floors of the building, allowing defenders to cover the base of the fortification wall.

The early 12th-century chronicler Lambert described the wooden keep on top of the motte at the castle of Ardres in northern France, where the:

“first storey was on the surface of the ground, where were cellars and granaries, and great boxes, tuns, casks, and other domestic utensils. In the storey above were the dwelling and common living-rooms of the residents in which were the larders, the rooms of the bakers and butlers, and the great chamber in which the lord and his wife slept…In the upper storey of the house were garret rooms…In this storey also the watchmen and the servants appointed to keep the house took their sleep”

Wooden structures on mottes could be protected by skins and hides to prevent them being easily set alight during a siege.

The bailey

The bailey was an enclosed courtyard overlooked by the motte and surrounded by a wooden fence called a palisade and another ditch. The bailey was often kidney-shaped to fit against a circular motte, but could be made in other shapes according to the terrain. The bailey would contain a wide number of buildings, including a hall, kitchens, a chapel, barracks, stores, stables, forges or workshops, and was the centre of the castle’s economic activity. The bailey was linked to the motte either by a flying bridge stretching between the two, or, more popularly in England, by steps cut into the motte. Typically the ditch of the motte and the bailey joined, forming a figure of eight around the castle. Wherever possible, nearby streams and rivers would be dammed or diverted, creating water-filled moats, artificial lakes and other forms of water defences.

In practice, there was a wide number of variations to this common design. A castle could have more than one bailey: at Warkworth Castle an inner and an outer bailey was constructed, or alternatively, several baileys could flank the motte, as at Windsor Castle. Some baileys had two mottes, such as those at Lincoln. Some mottes could be square instead of round, such as at Cabal Trump. Instead of single ditches, occasionally double-ditch defences were built, as seen at Berkhamsted. Local geography and the intent of the builder produced many unique designs.

Construction and maintenance

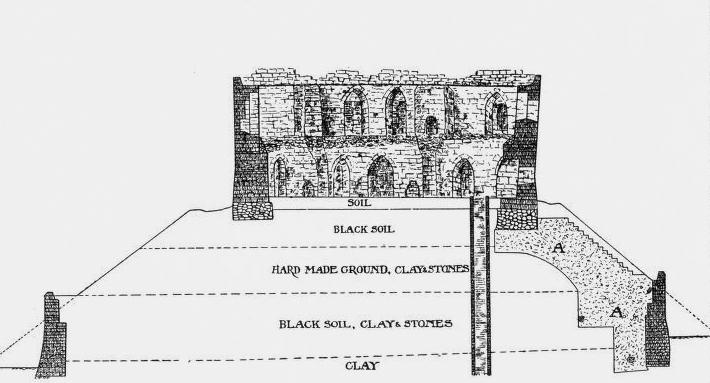

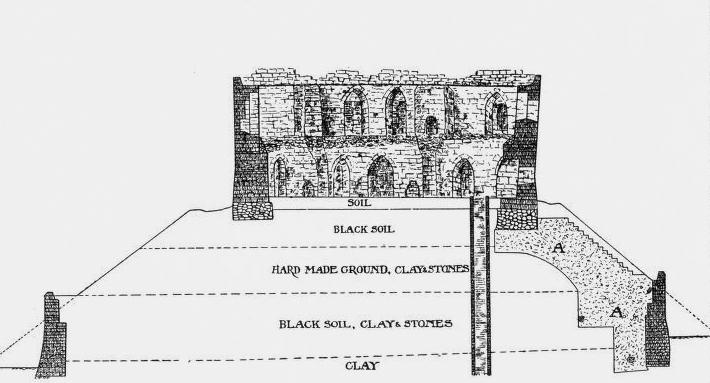

Various methods were used to build mottes. Where a natural hill could be used, scarping could produce a motte without the need to create an artificial mound, but more commonly much of the motte would have to be constructed by hand. Four methods existed for building a mound and a tower: the mound could either be built first, and a tower placed on top of it; the tower could alternatively be built on the original ground surface and then buried within the mound; the tower could potentially be built on the original ground surface and then partially buried within the mound, the buried part forming a cellar beneath; or the tower could be built first, and the mound added later.

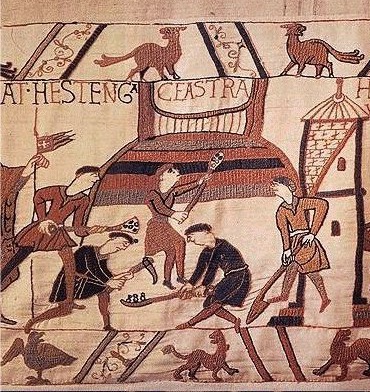

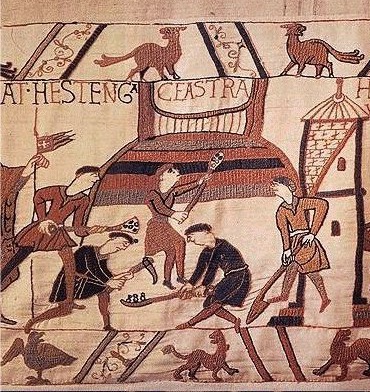

Regardless of the sequencing, artificial mottes had to be built by piling up earth; this work was undertaken by hand, using wooden shovels and hand-barrows, possibly with picks as well in the later periods. Larger mottes took disproportionately more effort to build than their smaller equivalents, because of the volumes of earth involved. The largest mottes in England, such as Thetford, are estimated to have required up to 24,000 man-days of work; smaller ones required perhaps as little as 1,000. Some contemporary accounts talk of some mottes being built in a matter of days, although these low figures have led to suggestions by historians that either these figures were an underestimate, or that they refer to the construction of a smaller designs than that later visible on the sites concerned.

Taking into account estimates of the likely available manpower during the period, historians estimate that the larger mottes might have taken between four and nine months to build. This contrasted favourably with stone keeps of the period, which typically took up to ten years to build. Very little skilled labour was required to build motte and bailey castles, which made them very attractive propositions if forced peasant labour was available, as was the case after the Norman invasion of England. Where the local workforce had to be paid the costs would rise quickly.

The type of soil would make a difference to the design of the motte, as clay soils could support a steeper motte, whilst sandier soils meant that a motte would need a more gentle incline. Where available, layers of different sorts of earth, such as clay, gravel and chalk, would be used alternatively to build in strength to the design. Layers of turf could also be added to stabilise the motte as it was built up, or a core of stones placed as the heart of the structure to provide strength. Similar issues applied to the defensive ditches, where designers found that the wider the ditch was dug, the deeper and steeper the sides of the scarp could be, making it more defensive.

Although militarily a motte was, as the historian Norman Pounds describes it, “almost indestructible”, they required frequent maintenance. Soil wash was a problem, particularly with steeper mounds, and mottes could be clad with wood or stone slabs to protect them. Over time, some mottes suffered from subsidence or damage from flooding, requiring repairs and stabilisation work.

History

Establishment of motte-and-bailey castles

The motte-and-bailey castle is a particularly northern European phenomenon, most numerous in Normandy and Britain, but also seen in Denmark, Germany, Southern Italy and occasionally beyond. The castles were first widely adopted in Normandy and Angevin territory in the 10th and 11th centuries.

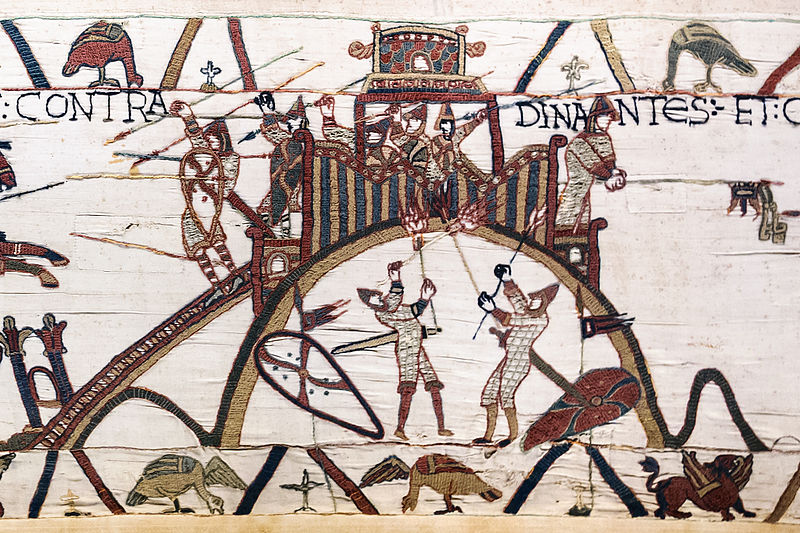

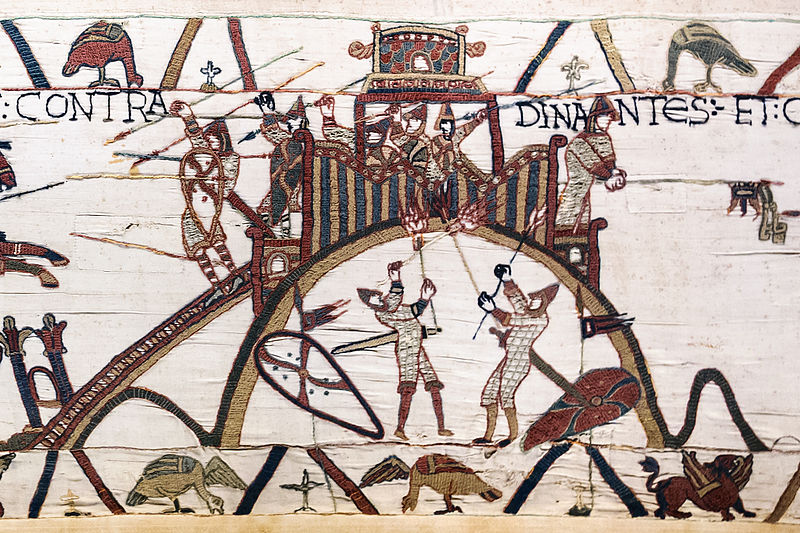

The earliest purely documentary evidence for motte-and-bailey castles in Normandy comes from between 1020 and 1040, but a combination of documentary and archaeological evidence pushes the date for the first motte and bailey castle, at Vincy, back to 979. William the Conqueror, as the Duke of Normandy, is believed to have adopted the motte-and-bailey design from neighbouring Anjou. Duke William went on to prohibit the building of castles without his consent through the Consuetudines et Justicie, with his legal definition of castles centring on the classic motte-and-bailey features of ditching, banking and palisading.

In England, William invaded from Normandy in 1066, resulting in three phases of castle building in England, around 80 percent of which were in the motte-and-bailey pattern. The first of these was the establishment by the new king of royal castles in key strategic locations, including many towns. These urban castles could make use of the existing town’s walls and fortification, but typically required the demolition of local houses to make space for them. This could cause extensive damage: records suggest that in Lincoln 166 houses were destroyed, with 113 in Norwich and 27 in Cambridge. The second and third waves of castle building in the late-11th century were led by the major magnates and then the more junior knights on their new estates.

Some regional patterns in castle building can be seen – relatively few castles were built in East Anglia compared to the west of England or the Marches, for example; this was probably due to the relatively settled and prosperous nature of the east of England and reflected a shortage of unfree labour for constructing mottes. In Wales, the first wave of the Norman castles were again predominantly made of wood in a mixture of motte-and-bailey and ringwork designs. The Norman invaders spread up the valleys, using this form of castle to occupy their new territories. After the Norman conquest of England and Wales, the building of motte-and-bailey castles in Normandy accelerated as well, resulting in a broad swath of these castles across the Norman territories, around 741 motte-and-bailey castles in England and Wales alone.

The Norman expansion into Wales slowed in the 12th century but remained an ongoing threat to the remaining native rulers. In response, the Welsh princes and lords began to build their own castles, frequently motte-and-bailey designs, usually in wood. There are indications that this may have begun from 1111 onwards under Prince Cadwgan ap Bleddyn, with the first documentary evidence of a native Welsh castle being at Cymmer in 1116. These timber castles, including Tomen y Rhodywdd, Tomen y Faerdre, Gaer Penrhôs, were of equivalent quality to the equivalent Norman fortifications in the area, and it can prove difficult to distinguish the builders of some sites from the archaeological evidence alone.

Decline and conversion

Motte-and-bailey castles became a less popular design in the mid-medieval period. Mottes ceased to be built in most of England after around 1170, although they continued to be erected in Wales and along the Marches. Many motte-and-bailey castles were occupied relatively briefly; in England many had been abandoned or allowed to lapse into disrepair by the 12th century.

One factor was the introduction of stone into castle building. The earliest stone castles had emerged in the 10th century, with stone keeps being built on mottes in France. [bit on spread] Although wood was a more powerful defensive material than was once thought, stone became increasingly popular for military and symbolic reasons. Some existing motte-and-bailey castles were converted to stone, with the keep and the gatehouse usually the first parts to be upgraded. Shell keeps were built on many mottes, circular stone shells running around the top of the motte, sometime protected by a further chemise, or low protective wall, around the base. By the 14th century, a number of motte and bailey castles had been converted into powerful stone fortresses.

Newer castle designs placed less emphasis on mottes. Square Norman keeps built in stone became popular following the first such construction in Langeais in 994. Several were built in England and Wales after the conquest; by 1216 there were around 100 in the country. These massive keeps could be either erected on top of settled, well established mottes, or could have mottes built around them – so-called “buried” keeps. The ability of mottes, especially newly built mottes, to support the heavier stone structures, was limited, and many needed to be built on fresh ground. Concentric castles, relying on several lines of baileys and defensive walls, made increasingly little use of keeps or mottes at all.

At the end of the 12th century the Welsh rulers began to build castles in stone, primarily in the principality of North Wales and usually along the higher peaks where mottes were unnecessary.

Bibliography

- Armitage, Ella S. (1912) The Early Norman Castles of the British Isles. London, UK: J. Murray.

- Besteman, Jan. C. (1984) “Mottes in the Netherland,” in Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. XII. pp. 211–224.

- Bradbury, Jim. (2009) Stephen and Matilda: the Civil War of 1139-53. Stroud, UK: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-3793-1.

- Brown, R. Allen. (1962) English Castles. London, UK: Batsford.

- Brown, R. Allen. (1989) Castles From the Air. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-32932-3.

- Brown, R. Allen. (2004) Allen Brown’s English Castles. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-069-6.

- Butler, Lawrence. (1997) Clifford’s Tower and the Castles of York. London, UK: English Heritage. ISBN 1-85074-673-7.

- Carpenter, David. (2004) Struggle for Mastery: The Penguin History of Britain 1066–1284. London, UK: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-014824-4.

- Châtelain, André. (1983) Châteaux Forts et Féodalité en Ile de France, du XIème au XIIIème siècle. Nonette: Créer. ISBN 978-2-902894-16-1.

- Colardelle, Michel and Chantal Mazard. (1982) “Les mottes castrales et l’évolution des pouvoirs dans le Alpes du Nord. Aux origines de la seigneurie,” in Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. XI, pp. 69–89.

- Cooper, Thomas Parsons. (1911) The History of the Castle of York, from its Foundation to the Current Day with an Account of the Building of Clifford’s Tower. London, UK: Elliot Stock.

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton. (2005) Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England. London, UK: Equinox. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8.

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton and Robert Higham. (2003) Medieval Castles. Princes Risborough, UK: Shire Publications. ISBN 978-0-7478-0546-5.

- Debord, André. (1982) “A propos de l’utilisation des mottes castrales,” in Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. XI, pp. 91–99.

- DeVries, Kelly. (2003) Medieval Military Technology. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-921149-74-3.

- Ekroll, Oystein. (1996) “Norwegian medieval castles: building on the edge of Europe,” in Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. XVIII, pp. 65–73.

- Héricher, Anne-Marie Flambard. (2002) “Fortifications de terre et résidences en Normandie,” in Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. XX pp. 87–100.

- Hulme, Richard. (2008) “Twelfth Century Great Towers – The Case for the Defence,” The Castle Studies Group Journal, No. 21, 2007-8.

- Jansen, Walter. (1981) “The international background of castle building in Central Europe,” in Skyum-Nielsen, Niels and Niels Lund (eds) (1981) Danish Medieval History: New Currents. Københavns, Denmark: Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 978-87-88073-30-0.

- Kaufmann, J. E. and H. W. Kaufmann. (2004) The Medieval Fortress: Castles, Forts and Walled Cities of the Middle Ages. Cambridge, US: Da Capo. ISBN 978-0-306-81358-0.

- Kenyon, John R. (2005) Medieval Fortifications. London, UK: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-7886-3.

- King, D. J. Cathcart. (1972) “The field archaeology of mottes in England and Wales: eine kurze übersichte,” in Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. V, pp. 107–111

- King, D. J. Cathcart. (1991) The Castle in England and Wales: An Interpretative History. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00350-4.

- Lepage, Jean-Denis. (2002) Castles and Fortified Cities of Medieval Europe: An Illustrated History. Jefferson, US: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1092-7.

- Liddiard, Robert. (2005) Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500. Macclesfield, UK: Windgather Press. ISBN 0-9545575-2-2.

- Lowry, Bernard. Discovering Fortifications: From the Tudors to the Cold War. Risborough, UK: Shire Publications. ISBN 978-0-7478-0651-6.

- McNeill, Tom. (2000) Castles in Ireland: Feudal Power in a Gaelic World. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-22853-4.

- De Meulemeester, Johnny. (1982) “Mottes Castrales du Comté de Flandres: État de la question d’apr les fouilles récent,” Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. XI, pp. 101–115.

- Nicolle, David. (1984) The Age of Charlemagne. Oxford, UK: Osprey. ISBN 978-0-85045-042-2.

- Nicholson, Helen J. (2004) Medieval Warfare: theory and practice of war in Europe, 300-1500. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-76330-8.

- O’Conor, Kieran. (2002) “Motte Castles in Ireland, Permanent fortresses, Residences and Manorial Centres,” in Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. XX, pp. 173–182.

- Pettifer, Adrian. (2000) Welsh Castles: a Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-778-8.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville. (1994) The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political history. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3.

- Pringle, Denys. “A castle in the sand: mottes in the Crusader east,” in Château Gaillard: études de castellologie médiévale. XVIII, pp. 187–190.

- Purton, Peter. (2009) A History of the Early Medieval Siege, c.450-1200. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-448-9.

- Robinson, John Martin. (2010) Windsor Castle: the Official Illustrated History. London, UK: Royal Collection Publications. ISBN 978-1-902163-21-5.

- Skyum-Nielsen, Niels and Niels Lund (eds) (1981) Danish Medieval History: New Currents. Københavns, Denmark: Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 978-87-88073-30-0.

- Simpson, Grant G. and Bruce Webster. (2003) “Charter Evidence and the Distribution of Mottes in Scotland,” in Liddiard, Robert. (ed) (2003) Anglo-Norman Castles. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-904-1.

- Stiesdal, Hans. (1981) “Types of public and private fortifications in Denmark,” in Skyum-Nielsen, Niels and Niels Lund (eds) (1981) Danish Medieval History: New Currents. Københavns, Denmark: Museum Tusculanum Press. ISBN 978-87-88073-30-0.

- Tabraham, Chris J. (2005) Scotland’s Castles. London, UK: Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-8943-9.

- Toy, Sidney. (1985) Castles: Their Construction and History. ISBN 978-0-486-24898-1.

- Van Houts, Elisabeth M. C. (2000) The Normans in Europe. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4751-0.

Attribution

The text of this page was adapted from “Motte-and-bailey castle” on the English language website Wikipedia, as the version dated 20 July 2017, and accordingly the text of this page is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Principle editors have included Hchc2009, and the contributions of all editors can be found on the history tab of the Wikipedia article.

Photographs on this page are drawn from the Wikimedia and the Flickr websites, as of 19 August 2019, and attributed and licensed as follows: adapted from “Dudley“, author Nigel Renny, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Castle Pulverbatch“, author AerialCam, released under CC BY-SA 4.0; “Twthill Motte”, author Cadw, released under Open Government Licence v.1.0; “Castle Acre Castle (2)“, author John Fielding, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Motte” (Public Domain); “Clifford Mound Crosssection” (Public Domain); “Bayeux Tapestry scene19 detail Castle Dinan” (Public Domain); “Recreation of Twthill Castle”, author Cadw, released under Open Government Licence v.1.0; adapted from “Carisbrooke Castle 14th century“, author Charles D P Miller, released under CC BY-SA 2.0.