In 1533 Henry broke with Pope Paul III in order to annul the long-standing marriage to his wife, Catherine of Aragon, and remarry. Catherine was the aunt of King Charles V of Spain, who took the annulment as a personal insult. As a consequence, France and the Empire declared an alliance against Henry in 1538, and the Pope encouraged the two countries to attack England. An invasion of England now appeared certain; that summer Henry made a personal inspection of some of his coastal defences, which had recently been mapped and surveyed: he appeared determined to make substantial, urgent improvements.

The resulting Device Forts represented a major, radical programme of work; the historian Marcus Merriman describes it as “one of the largest construction programmes in Britain since the Romans”, Brian St John O’Neil as the only “scheme of comprehensive coastal defence ever attempted in England before modern times”, while Cathcart King likened it to the Edwardian castle building programme in North Wales.

Although some of the fortifications are titled as castles, historians typically distinguish between the character of the Device Forts and those of the earlier medieval castles. Such castles were private dwellings as well as defensive sites, and usually played a role in managing local estates; Henry’s forts were organs of the state, placed in key military locations, typically divorced from the surrounding patterns of land ownership or settlements. Unlike earlier medieval castles, they were spartan, utilitarian constructions. Some historians such as King have disagreed with this interpretation, highlighting the similarities between the two periods, with the historian Christopher Duffy terming the Device Forts the “reinforced-castle fortification”.

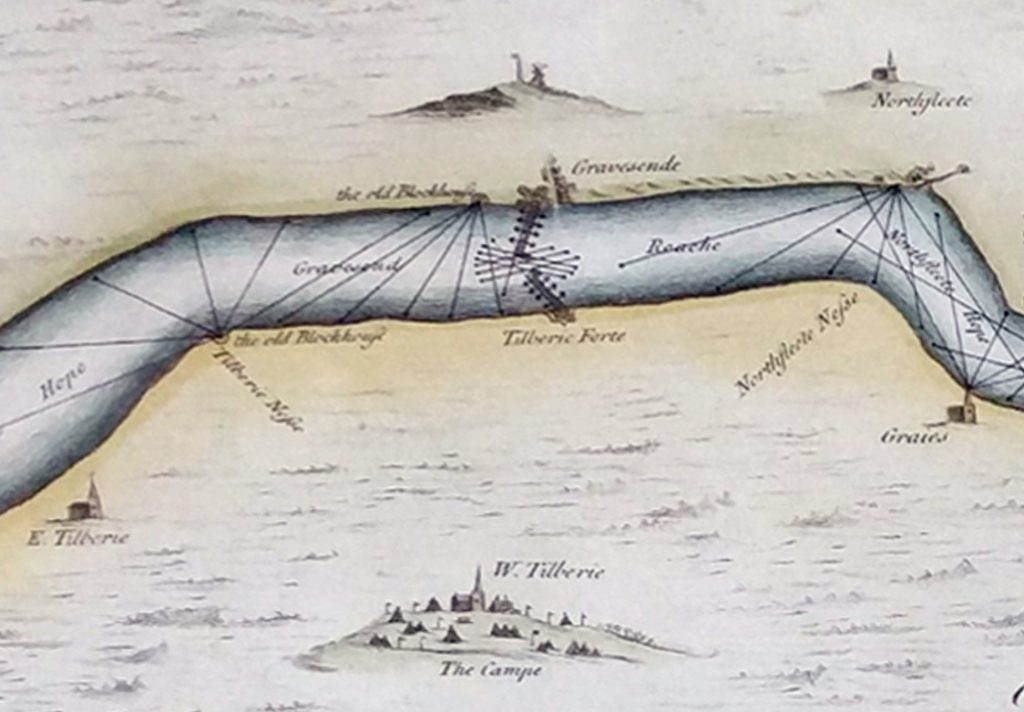

The forts were positioned to defend harbours and anchorages, and designed both to focus artillery fire on enemy ships, and to protect the gunnery teams from attack by those vessels. Some, including the major castles, including the castles of the Downs in Kent, were intended to be self-contained and able to defend themselves against attack from the land, while the smaller blockhouses were primarily focused on the maritime threat. Although there were extensive variations between the individual designs, they had common features and were often built in a consistent style.

The larger sites, such as Deal or Camber, were typically squat, with low parapets and massively thick walls to protect against incoming fire. They usually had a central keep, echoing earlier medieval designs, with curved, concentric bastions spreading out from the centre. The main guns were positioned over multiple tiers to enable them to engage targets at different ranges. There were far more gunports than there were guns held by the individual fortification. The bastion walls were pierced with splayed-gun embrasures, giving the artillery space to traverse and enabling easy fire control, with overlapping angles of fire. The interiors had sufficient space for gunnery operations, with specially designed vents to remove the black powder smoke generated by the guns. Moats often surrounded the sites, to protect against any attack from land, and they were further protected by what the historian B. Morley describes as the “defensive paraphernalia developed in the Middle Ages”: portcullises, murder holes and reinforced doors. The smaller blockhouses took various forms, including D-shapes, octagonal and square designs. The Thames blockhouses were typically protected on either side by additional earthworks and guns.

These new fortifications were the most advanced in England at the time, an improvement over earlier medieval designs, and were effective in terms of concentrating firepower on enemy ships. They contained numerous flaws, however, and were primitive in comparison to their counterparts in mainland Europe. The multiple tiers of guns gave the forts a relatively high profile, exposing them to enemy attack, and the curved surfaces of the hollow bastions were vulnerable to artillery. The concentric bastion design prevented overlapping fields of fire in the event of an attack from the land, and the tiers of guns meant that, as an enemy approached, the number of guns the fort could bring to bear diminished.

Some of these issues were addressed during the second Device programme from 1544 onwards. Italian ideas began to be brought in, although the impact of Henry’s foreign engineers seems to have been limited, and the designs themselves lagged behind those used in his French territories. The emerging continental approach used angled, “arrow-head” bastions, linked in a line called a trace italienne, to provide supporting fire against any attacker. Sandown Castle on the Isle of Wight, constructed in 1545, was a hybrid of traditional English and continental ideas, with angular bastions combined with a circular bastion overlooking the sea. Southsea Castle and Sharpenode Fort had similar, angular bastions. Yarmouth Castle, completed by 1547, was the first fortification in England, to adopt the new arrow-headed bastion design, which had further advantages over a simple angular bastion. Not all the forts in the second wave of work embraced the Italian approach however, and some, such as Brownsea Castle, retained the existing, updated architectural style.

Bibliography

Attribution

The text of this page was adapted from “Device Forts” on the English language website Wikipedia, as the version dated 30 July 2018, and accordingly this page is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Principle editors have included Hchc2009, 157.203.42.132 and Nev1, and the contributions of all editors can be found on the history tab of the Wikipedia article.

Photographs on this page include those drawn from the Wikimedia website, as of 22 July 2018, and attributed and licensed as follows: “Deal Castle Aerial View“, author Lievens Smits, released under CC BY-SA 3.0; “Yarmouth Castle, Isle of Wight“, author Christine Matthews, released under CC BY-SA 2.0.