Shell keeps were stone castle fortifications built in the 12th and 13th centuries, typically by constructing a circular wall around the top of a motte or ringwork, with buildings placed around the inside.

Not many were constructed across England and Wales, both because of their cost and because of the need for the motte to be sufficiently broad across the top to support the structure.

Design

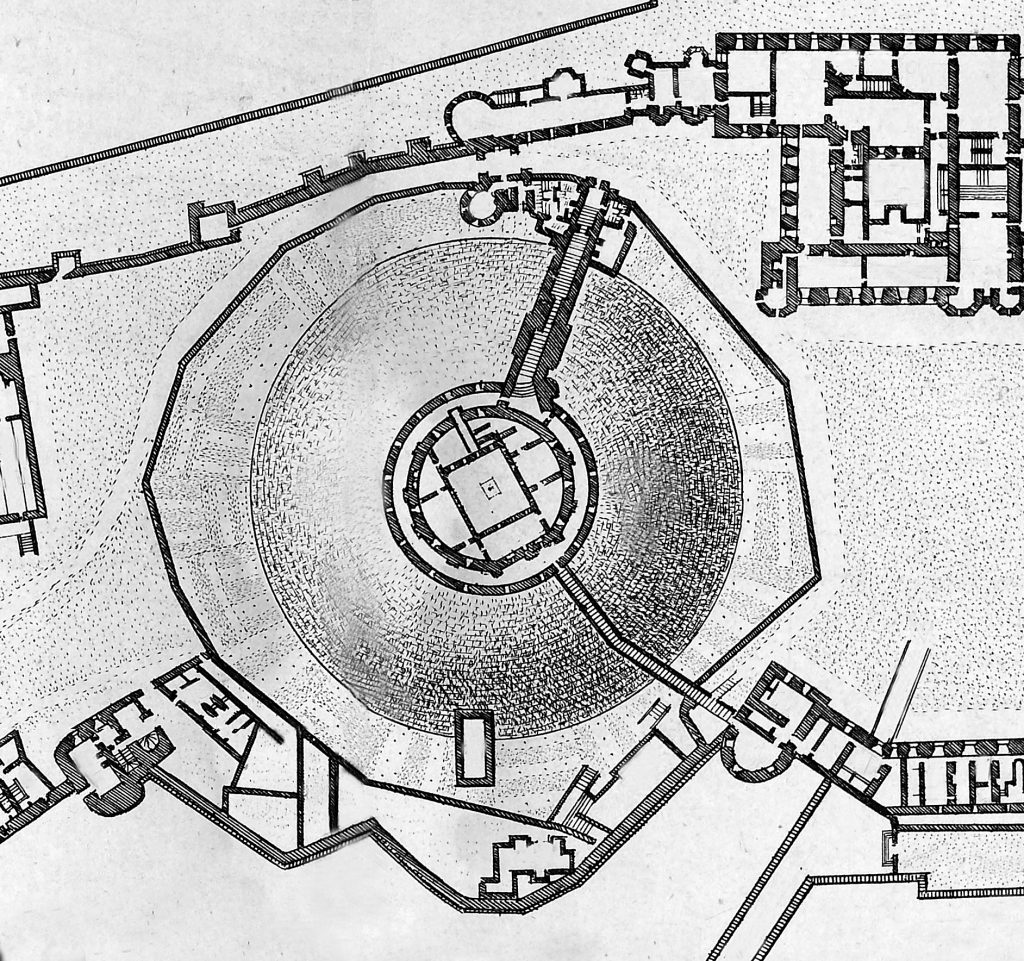

The term shell keep is used for any central castle fortification comprising a circular curtain wall, where the site usually quite broad in comparison to its height.

Typically, shell keeps were built by replacing the wooden keep on a motte, or the palisade on a ringwork, with a circular stone wall. Shell keeps were sometimes further protected by an additional low protective wall, called a chemise, around their base. Buildings could then be built around the inside of the shell, producing a small inner courtyard at the centre.

Shell keeps have some design similarities with the construction of circular donjons, or great towers, which could also be built on the top of mottes, surrounded by a circular protective wall. Donjons, however, were typically taller and narrower than a shell keep.

History

Shell keeps were one form of stone keep constructed during the medieval period. During the 10th century, a small number of stone keeps began to be built in France, such at the Château de Langeais: in the 11th century, their numbers increased as the style spread through Normandy across the rest of France and into England. Some existing motte-and-bailey castles were converted to stone, with the keep amongst usually the first parts to be upgraded, while in other cases new keeps were built from scratch in stone. These stone keeps were introduced into Ireland during the 1170s following the Norman occupation of the east of the country, where they were particularly popular amongst the new Anglo-Norman lords.

The reasons for the transition from timber to stone keeps are unclear, and the process was slow and uneven, taking many years to take effect across the various regions. Traditionally it was believed that stone keeps had been adopted because of the cruder nature of wooden buildings, the limited lifespan of wooden fortifications and their vulnerability to fire; recent archaeological studies have however shown that many wooden castles were as robust and as sophisticated as their stone equivalents. Some wooden keeps were not converted into stone for many years and were instead expanded in wood, such as at Hen Domen. Nonetheless, stone became increasingly popular as a building material for keeps for both military and symbolic reasons.

Two broad types of design in stone keeps emerged across France and England during the period: four-sided stone keeps, known as Norman keeps or great keeps in English – a donjon carré or donjon roman in French – and circular shell keeps.

The shell keep, called a donjon annulaire in French, was a style particularly popular in south-east England and across Normandy, although less so elsewhere. Restormel Castle is a classic example of this development, as is the later Launceston Castle; prominent Normandy and Low Country equivalents include Gisors and the Burcht van Leiden – these castles were amongst the most powerful fortifications of the period.

Although the circular design held military advantages over one with square corners – there were no square corners to target with siege weapons or to undermine – these really mattered from only the end of the 12th century onwards.

Instead, one major reason for adopting a shell keep design, was the circular design of the original earthworks exploited to support the keep – a shell keep could be better supported than a rectangular or square design. Some designs were less than circular in order to accommodate irregular mottes, such as that found at Windsor Castle. Another reason appears to have been the personal choice of the lord, and prevalent fashions. Richard of Cornwall, the Earl of Cornwall, for example, appears to have liked the design.

Bibliography

Attribution

The text of this page is licensed under under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Photographs on this page are drawn from the Wikimedia, Flickr, Albright-Knox websites, as of 19 August 2019, and attributed and licensed as follows: “Restormel Castle“, author Darrel Shilson, released under CC BY 2.0; adapted from “1761 plan of Windsor Castle” (Public Domain); “Launceston Castle, depicted by John Speed” (Public Domain); “Tamworth Castle“, author Pjposullivan1, released under CC BY-SA 2.0.