Norman keeps were a form of stone keep built in England and Wales following the invasion of 1066. The Normans brought the design from northern France, where a few of the strong, square designs had already been constructed.

The keeps were valued by the Normans for their military strength, but also typically had ceremonial functions. Symbolic of local lordship, they continued to be built long after the development of new siege weaponry had made them militarily outdated. Many still survive across the country, including at prominent national sites such as the Tower of London.

Terminology

Since the 16th century, the English word keep has commonly referred to large towers in castles. The word originates from around 1375 to 1376, coming from the Middle English term kype, meaning basket or cask, and was a term applied to the shell keep at Guînes, said to resemble a barrel. The term came to be used for other shell keeps by the 15th century. By the 17th century, the word keep lost its original reference to baskets or casks, and was popularly assumed to have come from the Middle English word keep, meaning to hold or to protect.

Early on, the use of the word keep became associated with the idea of a tower in a castle that would serve both as a fortified, high-status private residence and a refuge of last resort. The issue was complicated by the building of fortified Renaissance towers in Italy called tenazza that were used as defences of last resort and were also named after the Italian for “to hold” or “to keep”. By the 19th century, Victorian historians incorrectly concluded that the etymology of the words “keep” and tenazza were linked, and that all keeps had fulfilled this military function.

As a result of this evolution in meaning, the use of the term keep in historical analysis today can be problematic. Contemporary medieval writers used various terms for the buildings we would today call keeps. In Latin, they are variously described as turris, turris castri or magna turris – a tower, a castle tower, or a great tower. The 12th-century French came to term them a donjon, from the Latin dominarium “lordship”, linking the keep and feudal authority. Similarly, medieval Spanish writers called the buildings torre del homenaje, or “tower of homage.” In England, donjon turned into dungeon, which initially referred to a keep, rather than to a place of imprisonment.

While the term remains in common academic use, some academics prefer to use the term donjon, and most modern historians warn against using the term “keep” simplistically. The fortifications that we would today call keeps certainly did not necessarily form part of a unified medieval style, nor were they all used in a similar fashion during the period.

History

During the 10th century, a small number of stone keeps began to be built in France, such at the Château de Langeais: in the 11th century, their numbers increased as the style spread through Normandy across the rest of France and into England. Some existing motte-and-bailey castles were converted to stone, with the keep amongst usually the first parts to be upgraded, while in other cases new keeps were built from scratch in stone. These stone keeps were introduced into Ireland during the 1170s following the Norman occupation of the east of the country, where they were particularly popular amongst the new Anglo-Norman lords. Two broad types of design emerged across France and England during the period: four-sided stone keeps, known as Norman keeps or great keeps in English – a donjon carré or donjon roman in French – and circular shell keeps.

The reasons for the transition from timber to stone keeps are unclear, and the process was slow and uneven, taking many years to take effect across the various regions. Traditionally it was believed that stone keeps had been adopted because of the cruder nature of wooden buildings, the limited lifespan of wooden fortifications and their vulnerability to fire; recent archaeological studies have however shown that many wooden castles were as robust and as sophisticated as their stone equivalents. Some wooden keeps were not converted into stone for many years and were instead expanded in wood, such as at Hen Domen. Nonetheless, stone became increasingly popular as a building material for keeps for both military and symbolic reasons.

Stone keep construction required skilled craftsmen. Unlike timber and earthworks, which could be built using unfree labour or serfs, these craftsmen had to be paid and stone keeps were therefore expensive. They were also relatively slow to erect, due to the limitations of the lime mortar used during the period – a keep’s walls could usually be raised by a maximum of only 12 feet (3.6 metres) a year; the keep at Scarborough was not atypical in taking ten years to build. The number of such keeps remained relatively low: in England, for example, although several early stone keeps had been built after the conquest, there were only somewhere between ten and fifteen in existence by 1100, and only around a hundred had been built by 1216.

Architecture

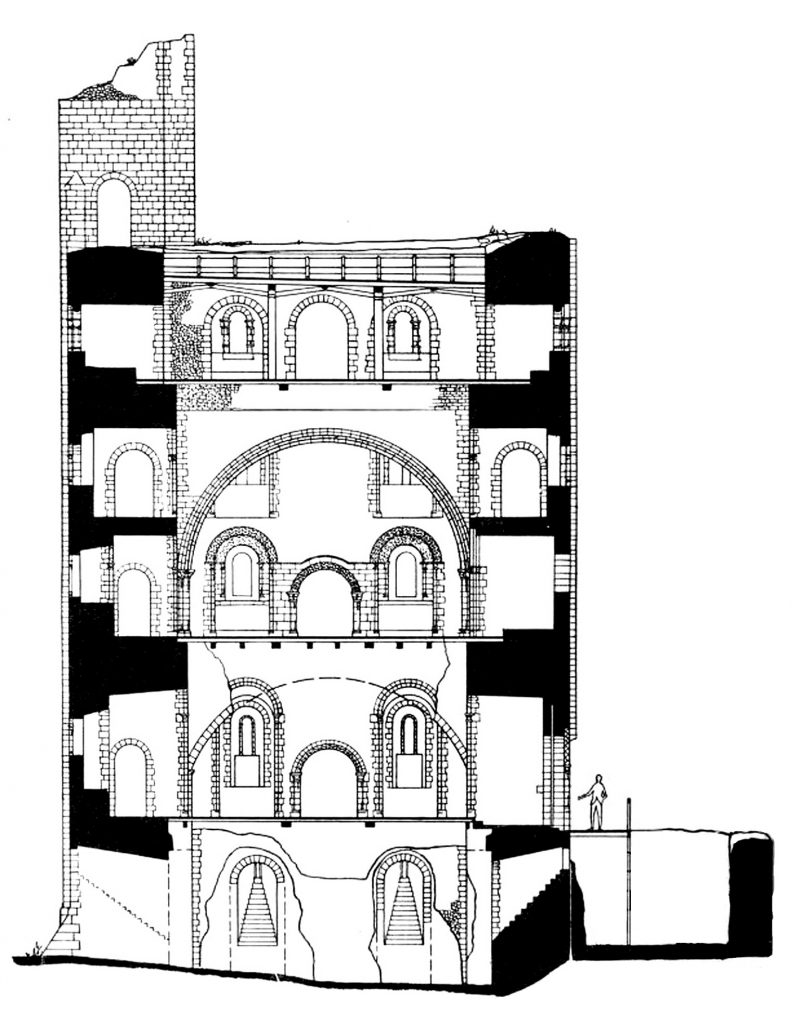

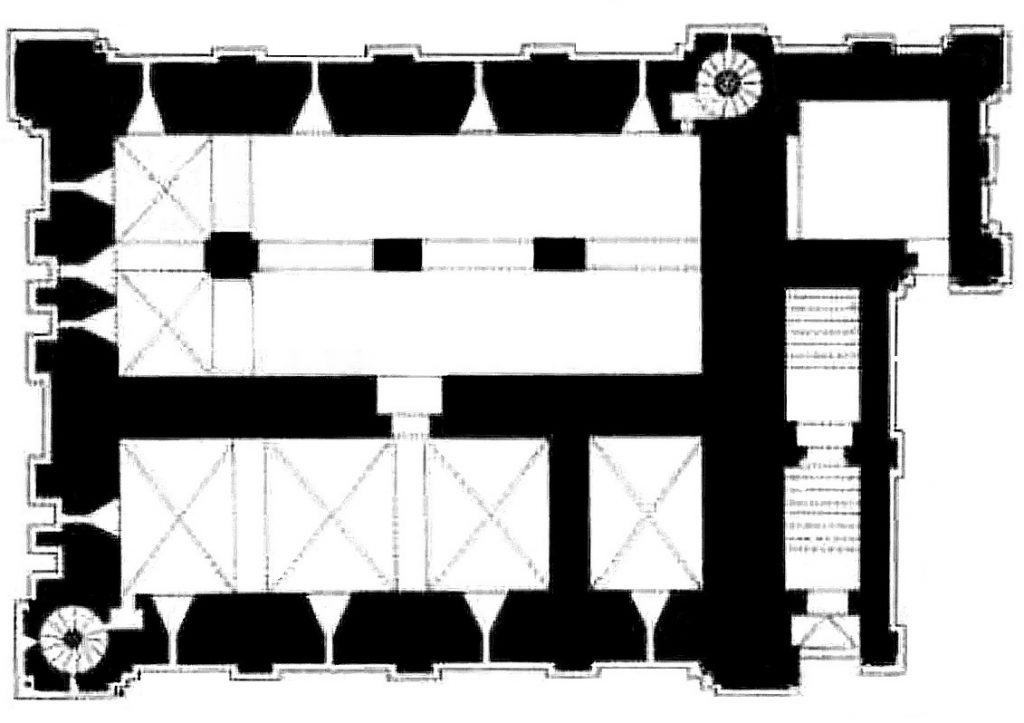

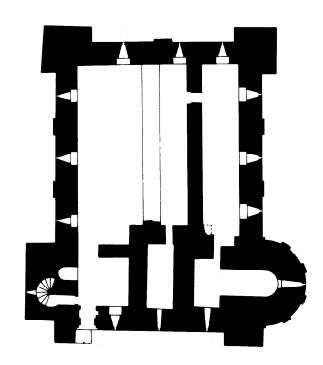

Norman keeps had four sides, with the corners reinforced by pilaster buttresses; some keeps, particularly in Normandy and France, had a barlongue design, being rectangular in plan with their length twice their width, while others, particularly in England, formed a square. These keeps could be up to four storeys high, with the entrance placed on the first storey to prevent the door from being easily broken down; early French keeps had external stairs in wood, whilst later castles in both France and England built them in stone. In some cases the entrance stairs were protected by additional walls and a door, producing a forebuilding.

The strength of the Norman design typically came from the thickness of the keep’s walls: usually made of ragstone, these could be up to 24 feet (7.3 metres) thick, immensely strong, and producing a steady temperature inside the building throughout summer and winter. The larger keeps were subdivided by an internal wall while the smaller versions had a single, slightly cramped chamber on each floor. Usually only the first floor would be vaulted in stone, with the higher storeys supported with timbers.

There has been extensive academic discussion of the extent to which Norman keeps were designed with a military or political function in mind, particularly in England. Earlier analyses of Norman keeps focused on their military design, and historians such as R. Brown Cathcart King proposed that square keeps were adopted because of their military superiority over timber keeps. Most of these Norman keeps were certainly extremely physically robust, even though the characteristic pilaster buttresses added little real architectural strength to the design.

Many of the weaknesses inherent to their design were irrelevant during the early part of their history. The corners of square keeps were theoretically vulnerable to siege engines and galleried mining, but before the introduction of the trebuchet at the end of the 12th century, early artillery stood little practical chance of damaging the keeps, and galleried mining was rarely practised. Similarly, the corners of a square keep created dead space that defenders could not fire at, but missile fire in castle sieges was less important until the introduction of the crossbow in the middle of the 12th century, when arrowslits began to be introduced.

Nonetheless, many stone Norman keeps made considerable compromises to military utility. Norwich Castle, for example, included elaborate blind arcading on the outside of the building and appears to have had an entrance route designed for public ceremony, rather than for defence. The interior of the keep at Hedingham could certainly have hosted impressive ceremonies and events, but contained numerous flaws from a military perspective.

Important early English and Welsh keeps such as the White Tower, Colchester, and Chepstow were all built in a distinctive Romanesque style, often reusing Roman materials and sites, and were almost certainly intended to impress and generate a political effect amongst local people. The political value of these keep designs, and the social prestige they lent to their builders, may help explain why they continued to be built in England into the late 12th century, beyond the point when military theory would have suggested that alternative designs were adopted.

Bibliography

- Anderson, William. (1980) Castles of Europe: From Charlemagne to the Renaissance. London, UK: Ferndale.

- Armitage, Ella S. (1912) The Early Norman Castles of the British Isles. London, UK: J. Murray.

- Baldwin, John W. (1991) The Government of Philip Augustus: Foundations of French Royal Power in the Middle Ages. Berkeley, US: University of California Press.

- Brindle, Steven and Brian Kerr. (1997) Windsor Revealed: New Light on the History of the Castle. London, UK: English Heritage.

- Brown, R. Allen. (1962) English Castles. London, UK: Batsford.

- Butler, Lawrence. (1997) Clifford’s Tower and the Castles of York. London, UK: English Heritage.

- Châtelain, André. (1983) Châteaux Forts et Féodalité en Ile de France, du XIème au XIIIème siècle. Nonette, France: Créer.

- Corp, Edward. (2009) “The Jacobite Court at Saint-Germain-en-Laye: Etiquette and the Use of the Royal Apartments,” in Creighton, Oliver Hamilton and Robert Higham. (2003) Medieval Castles. Princes Risborough, UK: Shire Publications.

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton. (2005) Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community, and Fortification in Medieval England. London, UK: Equinox.

- Cruickshanks, Eveline. (ed) (2009) The Stuart Courts. Stroud, UK: The History Press.

- DeVries, Kelly. (2003) Medieval Military Technology. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

- Dixon, Philip. (2002) “The Myth of the Keep,” in Meirion-Jones, Impey and Jones (ed) (2002).

- Durand, Philippe. (1999) Le Château-fort. Paris, France: Gisserot.

- Emery, Anthony. (2006) Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: Southern England. Cambridge, U: Cambridge University Press.

- Gomme, Andor and Alison Maguire. (2008) Design and Plan in the Country House: From Castle Donjons to Palladian Boxes. Yale, US: Yale University Press.

- Gondoin, Stéphane W. (2005) Châteaux-Forts: Assiéger et Fortifier au Moyen Âge. Paris, France: Cheminements.

- Heslop, T. A. (2003) “Orford Castle: Nostalgia and Sophisticated Living,” in Liddiard, Robert. (ed) (2003) Anglo-Norman Castles. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press.

- Higham, Robert and Philip Barker. (1992) Timber Castles. London, UK: Batsford.

- Hull, Lise E. (2006) Britain’s Medieval Castles. Westport, US: Praeger.

- Hulme, Richard. (2008) “Twelfth Century Great Towers – The Case for the Defence,” The Castle Studies Group Journal 21, pp. 209–229.

- Jones, Nigel R. (2005) Architecture of England, Scotland, and Wales. Westport, US: Greenwood Publishing.

- Kaufmann, J. E. and H. W. Kaufmann. (2004) The Medieval Fortress: Castles, Forts, and Walled Cities of the Middle Ages. Cambridge, US: Da Capo.

- Kenyon, J. and M. W. Thompson. (1995) “A Note on the Word ‘keep’,” Medieval Archaeology 38, pp. 175–6.

- Kenyon, John R. (2005) Medieval Fortifications. London, UK: Continuum.

- King, D. J. Cathcart. (1991) The Castle in England and Wales: An Interpretative History. London, UK: Routledge.

- Liddiard, Robert. (2005) Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism, and Landscape, 1066 to 1500. Macclesfield, UK: Windgather Press.

- Nicholson, Helen J. (2004) Medieval Warfare: Theory and Practice of War in Europe, 300–1500. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pettifer, Adrian. (2000) Welsh Castles: a Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press.

- Pettifer, Adrian. (2000) English Castles: a Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville. (1994) The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Purton, Peter. (2010) A History of the Late Medieval Siege, 1200–1500. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press.

- Rowan, A. J. (1952) The Castle Style in British Domestic Architecture in the 18th and 19th Centuries. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University, Unpublished Ph.D. thesis.

- Thompson, M. W. (1994) The Decline of the Castle. Leicester, UK: Harveys Books.

- Thompson, M. W. (2008) The Rise of the Castle. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Toy, Sidney. (1933) “The Round Castles of Cornwall,” Archaeologia 83, pp. 204–7.

- Toy, Sidney. (1985) Castles: Their Construction and History. New York, US: Dover Publications.

- Turner, Rick. (2006) Chepstow Castle. Cardiff, UK: Cadw.

Attribution

The text of this page was adapted from “Castles in Great Britain and Ireland” on the English language website Wikipedia, as the version dated 22 July 2018, and accordingly the text of this page is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Principle editors have included Hchc2009, Cameron and Nev1, and the contributions of all editors can be found on the history tab of the Wikipedia article.

Photographs on this page include those drawn from the Wikimedia and the Flickr websites, as of 19 August 2019, and attributed and licensed as follows: “Porchester castle keep 2011” author Geni, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “CastleRising2-wyrdlight-wiki“, author WyrdLight.com, released under CC BY-SA 4.0; “Rochester Castle Interior“, author David Ansley, released under CC BY-SA 1.0; “Goodrich Castle keep1“, author Pauline Eccles, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Goodrich keep plan alternative“, Crown Copyright (expired); adapted from “Castle Rising, plan” (Public Domain); “Colchester Castle Keep“, Crown Copyright (expired).