For the first century or so after the Norman invasion of England and Wales, keeps were typically substantial towers made from wood, or took the form of square Norman keeps.

During the second half of the 12th century, however, fashions shifted. Some circular keeps were introduced, appearing similar to those created by the Capetian French kings. Other new keeps were angular or polygonal in design. The reasons for this shift remain debated by historians – a mixture of military and symbolic logic may have been applied by their builders.

By the 14th century, some castle designs were rejecting the keep altogether. Quadrangle castles, for example, did not include them, nor did the concentric castles constructed by Edward I in North Wales. It became popular to construct increasingly large and impressive gatehouses that replaced the keep as the key focus of a castle’s design.

In the late medieval period, a few castles were constructed with grand keeps, huge central towers with unique designs, symbolic of the great power of their lords. As castle building came to an end, however, the keep had almost entirely been replaced by the gatehouse as the symbolic heart of the fortification.

12th and 13th centuries

During the second half of the 12th century, a range of new keep designs began to appear across England, breaking the previous unity of the regional designs. One traditional explanation for these developments emphasises the military utility of the new approaches, arguing, for example, that the curved surfaces of the new keeps helped to deflect attacks, or that they drew on lessons learnt during the Crusades from Islamic practices in the Levant. More recent historical analysis, however, has emphasised the political and social drivers that underlay these mid-medieval changes in keep design.

Through most of the 12th century, France was divided between the Capetian kings, ruling from the Île-de-France, and kings of England, who controlled Normandy and much of the west of France. Within the Capetian territories, early experimentation in new keep designs began at Houdan in 1120, where a circular keep was built with four round turrets; internally, however, the structure remained conventionally square. A few years later, Château d’Étampes adopted a quatrefoil design. These designs, however, remained isolated experiments.

In the 1190s, however, the struggle for power in France began to swing in favour of Philip II, culminating in the Capetian capture of Normandy in 1204. Philip II started to construct completely circular keeps, such as the Tour Jeanne d’Arc, with most built in his newly acquired territories. The first of Philip’s new keeps was begun at the Louvre in 1190 and at least another twenty followed, all built to a consistent standard and cost. The architectural idea of circular keeps may have come from Catalonia, where circular towers in castles formed a local tradition, and probably carried some military advantages, but Philip’s intention in building these new keeps in a fresh style was clearly political, an attempt to demonstrate his new power and authority over his extended territories. As historian Philippe Durand suggests, these keeps provided military security and were a physical representation of the renouveau capétien, or Capetian renewal.

Keep design in England began to change only towards the end of the 12th century, later than in France. Wooden keeps on mottes ceased to be built across most of England by the 1150s, although they continued to be erected in Wales and along the Welsh Marches. By the end of the 12th century, England and Ireland saw a handful of innovative angular or polygonal keeps built, including the keep at Orford Castle, with three rectangular, clasping towers built out from the high, circular central tower; and the famous polygonal design at Conisborough. Despite these new designs, square keeps remained popular across much of England and, as late as the 1170s, square Norman great keeps were being built at locations such as Newcastle. Circular keep designs similar to those in France only really became popular in the Welsh Marches for a short period during the early 13th century.

These Anglo-Norman designs were informed both by military thinking and by political drivers. The keep at Orford has been particularly extensively analysed in this regard, and although traditional explanations suggested that its unusual plan was the result of an experimental military design, more recent analysis concludes that the design was instead probably driven by political symbolism and the need for Henry to dominate the contested lands of East Anglia. The architecture would, for mid-12th century nobility, have summoned up images of King Arthur or Constantinople, then the idealised versions of royal and imperial power. Even formidable military designs such as that at Château Gaillard in Normandy were with political effect in mind. Gaillard was built by Richard I to reaffirm Angevin authority in a fiercely disputed conflict zone and the keep, although militarily impressive, contained only an anteroom and a royal audience chamber, and was built on soft chalk and without an internal well, both serious defects from a defensive perspective.

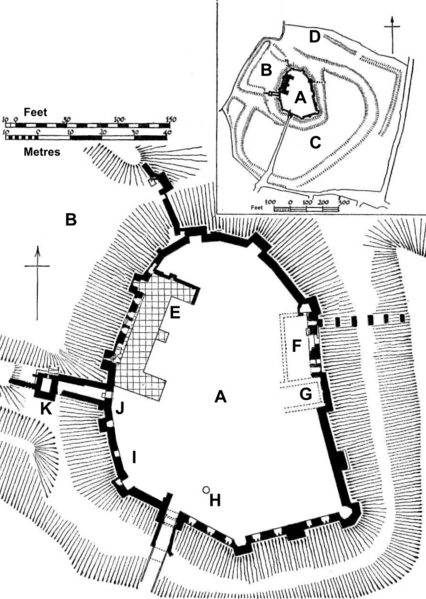

Several designs for new castles emerged that made keeps unnecessary. One such design was the concentric approach, involving exterior walls guarded with towers, and perhaps supported by further, concentric layered defenses: thus castles such as Framlingham never had a central keep. Military factors may well have driven this development: R. Brown, for example, suggests that designs with a separate keep and bailey system inherently lacked a co-ordinated and combined defensive system, and that once bailey walls were sophisticated enough, a keep became militarily unnecessary. In England, gatehouses were also growing in size and sophistication until they too challenged the need for a keep in the same castle. The classic Edwardian gatehouse, with two large, flanking towers and multiple portcullises, designed to be defended from attacks both within and outside the main castle, has been often compared to the earlier Norman keeps: some of the largest gatehouses are called gatehouse keeps for this reason.

The quadrangular castle design that emerged in France during the 13th century and later spread into England was another development that removed the need for a keep. Castles had needed additional living space since their first emergence in the 9th century; initially this had been provided by halls in the bailey, then later by ranges of chambers alongside the inside of a bailey wall, such as at Goodrich. But French designs in the late 12th century took the layout of a contemporary unfortified manor house, whose rooms faced around a central, rectangular courtyard, and built a wall around them to form a castle. The result was a characteristic quadrangular layout with four large, circular corner towers. It lacked a keep, which was not needed to support this design.

14th–16th centuries

The end of the medieval period saw a fresh resurgence in the building of keeps in western castles. Some castles continued to be built without keeps: the Bastille in the 1370s, for example, combined a now traditional quadrangular design with machicolated corner towers, gatehouses and moat; the walls, innovatively, were of equal height to the towers. This fashion became copied in England, particularly amongst the nouveau riche, for example at Nunney. The royalty and the very wealthiest in England, however, began to construct a small number of keeps on a much larger scale than before, in England sometimes termed tower keeps, as part of new palace fortresses. This shift reflected political and social pressures, such as the desire of the wealthiest lords to have privacy from their growing households of retainers, as well as the various architectural ideas being exchanged across the region, despite the ongoing Hundred Years War between France and England.

The 15th and 16th centuries saw a small number of English and occasional Welsh castles develop still grander keeps. The first of these large tower keeps were built in the north of England during the 14th century, at locations such as Warkworth. They were probably partially inspired by designs in France, but they also reflected the improvements in the security along the Scottish border during the period, and the regional rise of major noble families such as the Percies and the Nevilles, whose wealth encouraged a surge in castle building at the end of the 14th century. New castles at Raby, Bolton, and Warkworth Castle took the quadrangular castle styles of the south and combined them with exceptionally large tower keeps to form a distinctive, northern style. Built by major noble houses, these castles were typically even more opulent than the smaller castles like Nunney, built by the nouveau riche. They marked what historian Anthony Emery has described as a “…second peak of castle building in England and Wales,” following on from the Edwardian designs at the end of the 14th century.

In the 15th century, the fashion for the creation of very expensive, French-influenced palatial castles featuring complex tower keeps spread, with new keeps being built at Wardour, Tattershall, and Raglan Castle. In central and eastern England, some keeps began to be built in brick, with Caister and Tattershall forming examples of this trend. These tower keeps were expensive buildings to construct, each built to a unique design for a specific lord and, as the historian Norman Pounds has suggested, they “were designed to allow very rich men to live in luxury and splendour.”

At the same time as these keeps were being built by the extremely wealthy, much smaller, keep-like structures called tower houses or peel towers were built across northern England, often by relatively poorer local lords and landowners. A tower house would typically be a tall, square, stone-built, crenelated building. Most academics agree that tower houses should not be classified as keeps but rather as a form of fortified house.

Decline

As the 16th century progressed, keeps fell out of fashion once again. In England, the gatehouse also began to supplant the keep as the key focus for a new castle development. By the 15th century, it was increasingly unusual for a lord to build both a keep and a large gatehouse at the same castle, and by the early 16th century, the gatehouse had easily overtaken the keep as the more fashionable feature: indeed, almost no new keeps were built in England after this period.

The classical Palladian style began to dominate European architecture during the 17th century, causing a further move away from the use of keeps. Buildings in this style usually required considerable space for the enfiladed formal rooms that became essential for modern palaces by the middle of the century, and this style was impossible to fit into a traditional keep. The keep at Bolsover Castle in England was one of the few to be built as part of a Palladian design.

Bibliography

Attribution

Photographs on this page include those drawn from the Wikimedia and the Flickr websites, as of 19 August 2019, and attributed and licensed as follows: “ConisbroughCastle2“, author Rob Bendall, released for reuse for any purpose, subject to attribution; “Orford Castle Keep“, author Keith Roper, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Skenfrith Castle“, author Davidmholmes51, released under CC BY-SA 4.0; “Framlingham Castle plan” (Crown Copyright, expired); “Nunney Castle (2)“, author Mike Searle, released under CC BY-SA 2.0; “Raglan Reconstruction“, author Cadw, released under Open Government Licence 1.0; “Bolsover Castle Keep“, author Amateur with a Camera, released under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.