The architecture of castles has been extensively studied over the last 150 years. Some approaches have focused on the military functions of their defences; others on the social and cultural roles of their buildings and design. This article discusses some of the basic concepts in the design of castles – what made up a medieval castle, what landscape surrounded them, and the materials used in their construction.

Composition of a castle

Baileys and wards

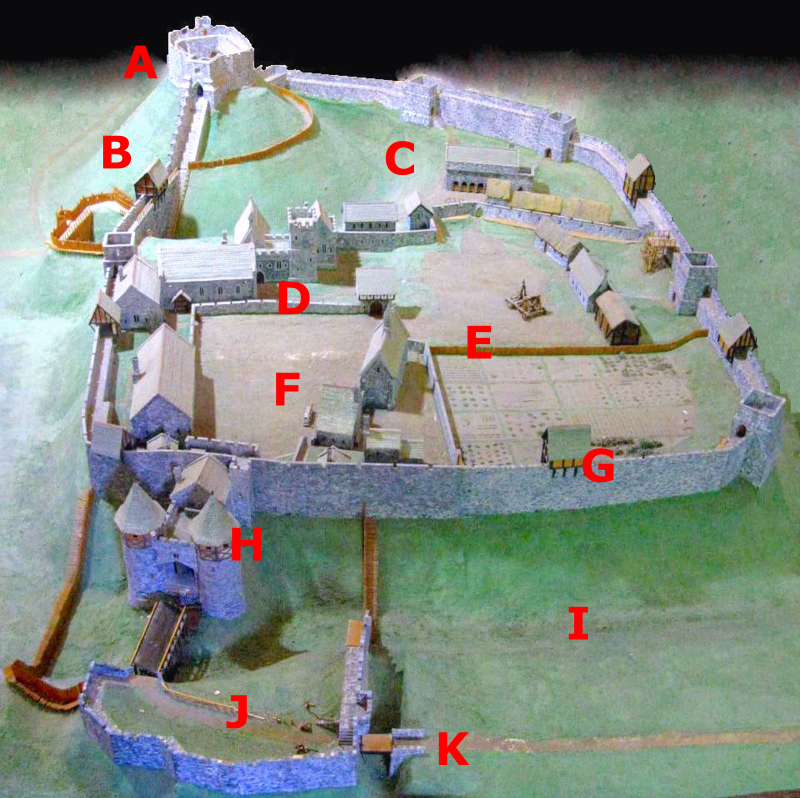

Most of a castle was made up by relatively open, flat, enclosed spaces called baileys or wards. In the earliest castles, these were defined by earthworks and timber defences; in later versions, these were replaced by stone. Castles might have up to three or four baileys of varying size, linked by gateways or bridges.

Baileys had multiple functions, both military – protecting key parts of a castle such as the keep – and domestic – providing space for the castle’s inhabitants to live and work. Many baileys held various buildings, while others seem to have been kept entirely open, perhaps to host assemblies of soldiers and their mounts when needed. In some cases, baileys might have felt like a courtyard, surrounded by solid ranges of buildings; in other instances, they would have seemed more like a simple defended or walled space.

In castles with two baileys, the one closest to the motte or keep was usually termed the inner or upper bailey. This would hold the great hall and the private accommodation of the lord. The other, the outer or lower bailey, would be used to accommodate the garrison and any ancillary buildings. In some cases, castles with only one large bailey would later subdivide it with a wall, reproducing the inner and outer distinction.

Earthworks and water

Earthworks were crucial to most castles. Early castles depended on extensive defences comprising banks of earth, protected by timber defences, and defensive ditches. These might reuse older Iron Age defences or be built on top of natural features, sometimes revetted to improve the angle to their slope.

Where possible, castle builders tried to turn some of the defensive ditches into a wet moat, filled with water from local rivers or natural springs. Sometimes, this could involve complex water management systems. In other cases, wider areas around the castle would be flooded to produce shallow, defensive water features; these reflective surfaces could also play an ornamental function.

Many Norman castles had cone-shaped earthworks called mottes: these were large features at the core of the fortification, supporting a timber keep. As time went by, and many mottes compacted sufficiently to withstand the additional weight, these keeps were replaced in stone, and further stone walls added to the base of the keeps. Some later castles were constructed with earth amassed around central towers to give the impression of a much older motte.

Towards the end of the medieval period, the rise of gunpowder artillery made earthwork defences critical again. Some castles were refortified with extensive earthwork bastions, typically faced with stone, with the same features used in some of Henry VIII’s new Device Forts.

Keeps

Most Norman castles included a keep, a central major tower, typically placed on top of a motte. These early keeps had a clear military function, being very difficult to attack before the advent of heavy siege weapons, but also often contained living space for the castle’s lord.

A handful of Norman keeps were built in stone, with a characteristic square design and simple internal features. Such keeps became heavily symbolic of a lord’s right over a castle, and as a result some were constructed long after they had become militarily redundant. Some later stone keeps were circular, following French innovations, and some enclosed existing earthworks to form shell keeps.

Keeps eventually fell out of fashion, but made a resurgence in the late medieval period. New castles in the later period often included grand, elaborate keeps containing complex sets of accommodation for the lord and his guests.

Gatehouses

Early castles had relatively simple gateways controlling access to the castle. These might include a main gate, often facing the settlement, as well as postern gates, providing a rear or emergency exit to the castle.

A few castles had watergates, managing access to a neighbouring river or waterway. Fortified towns could also have gateways in their defences with either complete gates or, in more basic instances, symbolic obstacles such as a wooden bar.

As time progressed, gateways were enlarged and became gatehouses, often with vaulted entrance halls, porters’ lodges and accommodation over the top. Portcullises formed an addition to reinforced gate doors. It became fashionable to build very large gatehouses that removed the need for a keep in a castle design. Major towns and cities treated their large gatehouses as symbolic of their civic independence – they could be heavily decorated as a result.

Walls, towers and bridges

The earliest castles in England were defended by wooden ramparts placed on top of earthwork banks and ditches. Stone walls gradually replaced many of these, with some walls reinforced internally with intra-mural timbers. External castle walls are often called curtain walls, enclosing a bailey or ward. Barbicans, walled enclosures positioned outside of a gatehouse, provided an additional layer of protection for the main castle.

More substantial walls and ramparts might be built with wallwalks along them, allowing the garrison to walk along the top. Battlements, machicolations and similar defensive features became common, particularly once crossbows became common on the battlefield. Weak corners of walls might be further protected with stone spurs, or parts of the wallwalk designed with wooden segments which could be withdrawn or destroyed in an emergency.

Castle and town walls were frequently protected with mural towers, providing additional protection for a garrison, and offering up the possibility of enfilading fire along the lines of the walls. Mural towers took various forms – they could be circular, semi-circular or square; some had solid backs, others were open on the reverse. Some were large enough to support defensive siege weapons.

Early castle walls and tower lacked arrow-slits: the bows used in the period were quite light and less suitable for defences. As the crossbow was adopted in medieval warfare – a weapon which could easily be used within confined spaces – arrow-slits became more more common in castles, typically with wide internal embrasures. With the advent of concentric defences in the 13th century, complex patterns of arrow-slits were designed to enable overlapping fields of fire.

Specially-shaped slits called gunports were introduced in the 14th century, allowing the use of hand-cannon and other light gunpowder weapons. For a while, these were highly fashionable and were sometimes constructed in quite awkward locations with little military value, but from where they could be easily seen by visitors or guests. The tops of larger towers or bastions could support artillery: initially weapons such as catapults or trebuchets, and later gunpowder artillery.

Not all towers were defensive in design; some were intended as viewing towers, from where a lord or his guests could admire the surrounding estates. Towers could also house accommodation, ancillary functions or stores.

Many castles had bridges, providing access from the outside or linking parts of the fortification separated by banks and ditches. Early bridges were typically constructed in timber, often later replaced partially or in total with stone. Drawbridges, turning-bridges and other similar structures were sometimes used in later castles, all designed to deny an attacker access in a conflict.

Buildings

Castles contained a wide range of different buildings. Estimates vary according to the period, location and size of the castle, but while some castles might have had largely open baileys with only a few large buildings, other castles would have been tightly crammed with various small dwellings and facilities.

Many of these buildings would have been used by the lord of the castle and his immediate family or staff. The great hall, for example, would have been the centre of daily life in any early castle, used for business, ceremonies and dining. Several large chambers would have provided additional accommodation, and a chapel would have catered to the lord’s spiritual needs. In a castle with a large keep, these might have been located inside the tower, but in other cases these would have been distinct buildings within the inner bailey.

Kitchens and bakeries could be located within a keep, but were often constructed separately, due to the fire risk. These and similar buildings were also often within the inner bailey for convenience.

Later castle builders placed more emphasis on the emerging concept of privacy. The great hall remained a key location for formal events, but the lord of a castle and his guests came to expect complex sets of chambers, with privacy and space for their servants built in. These usually took the form of new ranges of buildings. Solars, separate living spaces away from the main hall, and luxuriously decorated private chambers became the norm. Gloriettes were built, sets of rooms from where the surrounding estates or gardens could be viewed.

Castles required a wide range of ancillary buildings, including barns, stables and blacksmiths’ forges. These were usually placed in an outer bailey. The castle mill, essential for grinding corn into bread, which formed the basis for the daily diet at this time, would be located as close to the castle as possible, but needed a source of running water.

Most castles drew their water from wells inside the walls; some well shafts could be extremely deep. Later castles also made use of lead piping to bring water into the castle. Effluence was typically removed using simple privies or garderobes, emptying into the moat or ditches.

Landscape

Castles were usually designed to fit within their surrounding landscape, which could itself be modified to suit the new fortification. The Norman invaders preferred to place their castles so as to overlook settlements, or to appear dramatically situated on hills and valleys above them. Early urban castles were placed within existing defensive features such as town walls, and many later castles formed part of planned settlements.

For most of the medieval period, castles were symbolic of lordship over the surrounding estates, and it was expected that a lord who owned or built a castle would also construct the other major symbols of lordship on his lands. This would include a dovecote, a religious establishment such as a monastery, fishponds, and a mill. These might be positioned so that they could be seen by visitors arriving at the castle.

Castles were often linked to deer parks, used for hunting and a wide variety of economic activity. Castles might be constructed specifically to provide accommodation for a lord to use when using a deer park, or areas of agricultural land might be emparked – cleared of other residents – to create one near to a castle. Some royal castles were tied to royal forests, and had special roles in managing the law and economic activities there.

Many castles had gardens and orchards, with vineyards common through much of the period. Their style varied throughout the period but they played an important function in the social life of a castle, as well as helping to provide food for the inhabitants. Even the heavily-defended castle built by Edward I at Conwy in newly-occupied North Wales had an ornamental garden within it, intended for use by his queen.

Materials

Castles were constructed using a wide range of materials, but all castles depended heavily on earth and timber. Early castles might involve the moving of huge quantities of earth to either reinforce existing natural features, or construct entirely new ones. Ditches were dug out and the spoil piled up. Timber was to build defences, such as palisades, as well as the buildings within. Larger buildings required long timbers from ancient trees to support their roofs and internal floors.

Stone was used for a handful of castles from the time of the Conquest onwards, but became increasingly prevalent during the medieval period. The raw material was ideally sourced locally, as transporting heavy goods was difficult, but finer stone could be shipped over long distances. Crude rubble might be used for the interior of walls, while finer ashlar stone was used to face the exterior of walls or for carving finer features, such as door frames or windows. Stonework could create elaborate vaulting and other complex designs.

Some later castles made use of brick, typically made from local clay and baked close to the construction site. Brick was quicker to build with than stone, requiring no carving and shaping, and the construction work could be planned more precisely.

The decorative finish of the materials was usually important. Stone and brick could be used to create different textures, banding of different colours, and patterns. External walls could be finished with whitewash, giving the fortification a more striking design, and interior surfaces could be painted with murals, patterns or other designs, or hung with decorative fabrics.

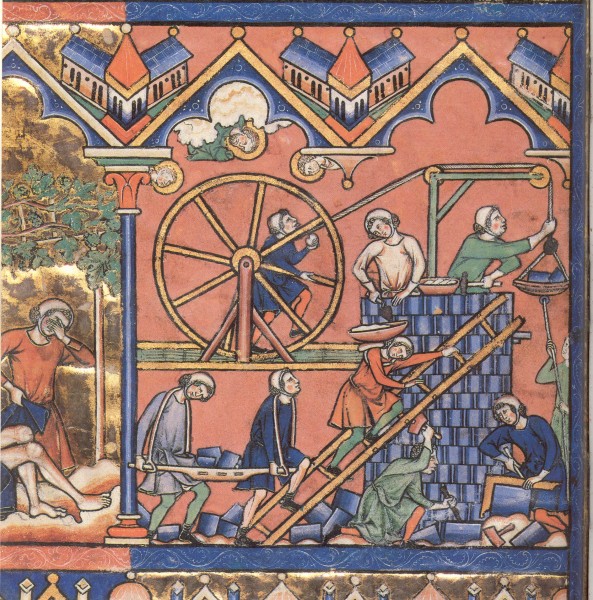

A wide variety of skills were necessary to construct castles. In the 11th and 12th centuries, master carpenters typically supervised construction work, often combining both military and civil engineering roles. By the 13th century, chief masons had supplanted them, reflecting the changing character of castle design; masons also oversaw the later construction of castles in brick. Dykers specialised in the earthworks around ditches and moats, while miners and quarrymen could be deployed when necessary to cut through rock.

Bibliography

Attribution

The text of this page is licensed under under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Images on this page included those from the Flickr and Wikimedia websites, as of 23 November 2019, and attributed and licensed as follows: “Carisbrooke Castle“, author Charles D. P. Miller, modified by Hchc2009, released under CC BY 2.0; “Castle Rising, aerial photography“, author John Fielding, released under CC BY 2.0; “Carisbrooke Castle bastion“, author Nilfanion, released under CC BY-SA 3.0; “Early Norwich Castle“, author Leo Reynolds, released under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0; “SDJ Harlech Castle Gatehouse“, author Gwen Hitchcock, released under CC BY-SA 3.0; “Kirby Muxloe Castle“, author Bobrad, released under CC BY-SA 3.0; “Grosmont Castle arrow slit“, author Nilfanion, released under CC BY-SA 4.0; “Reconstruction of life in the Great Hall” (Crown Copyright, expired); “Winchester Castle arbour“, author Jim Limwood, released under CC BY 2.0; “Treadmillcrane” (Public Domain).